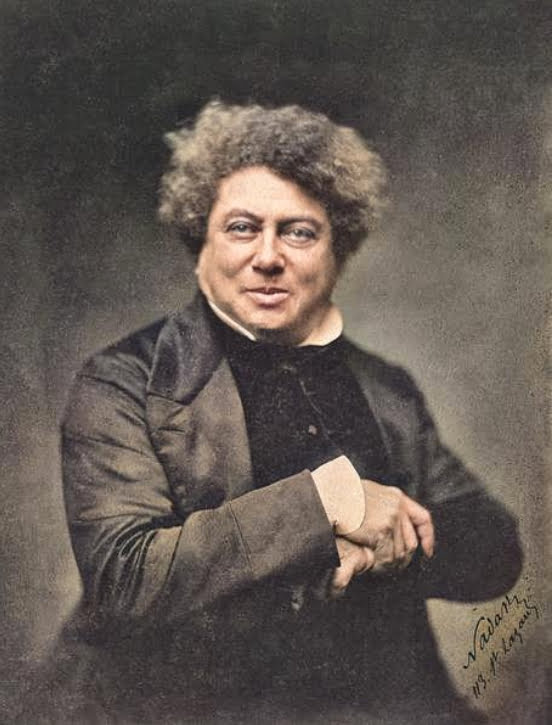

In which we explore a lost herring tradition of Reims and a lost Alexandre Dumas novel

PROCESSION OF THE HERRINGS

In the section on herrings in his Dictionary of Cuisine Alexandre Dumas notes:

A bizarre custom involving the canons of Reims Cathedral survived until the C16th. On Holy Wednesday, after Tenebrae, they would process to the Church of St Remy in twos, each dragging a herring on a string. Each canon was trying to step on the herring of the one in front of him, while saving his own from the one behind. It was only possible to put an end to this extravagant custom by banning the procession.

The dictionary was a labour of love, published posthumously in 1873, but Dumas seems to have lifted his account of the procession from the History of Civil and Religious Festivals, Ancient and Modern Customs of Flanders and a large number of French Towns by Madame Clément, née Hémery (1845). In her account, she adds the information that:

Church records for the church in Reims say that the procession had been instituted in 1429 for the coronation of Charles VII, a display of contempt for the English, who celebrated the so-called Day of the Herring, in commemoration of the Duke of Bourbon’s defeat, trying to capture a convoy of herrings to relieve Orleans, besieged by the English, who were nevertheless unable to stop Joan of Arc lifting the siege and enabling the King’s coronation at Reims.

The Duke of Bourbon’s defeat was at the Battle of the Herrings at Rouvray in February 1429. The convoy he was attacking was destined for the besieging forces and its successful defence was led by John Fastolf, on whom Shakespeare (playing fast and loose with his dates) based the character Falstaff.

Dumas drops Madame Clément’s final paragraph on the subject altogether. Notwithstanding its swashbuckling potential. Was he holding it back for one last novel? La Procession des Harengs ou Les Trois Arquebusquetaires: Un Prequel? The gun existed in 1429, even though it was the addition of a shoulder stock, priming pan and matchlock mechanism in the late 15th century, which turned the arquebus into a handheld firearm and also the firearm equipped with a trigger (Wikipedia). But what are such details between great writers?

…Due to the schemings of Hundred Years War profiteer Regnault de Chartres, Archbishop of Reims (later Cardinal Regnault, Chancellor of France) the cathedral canons are left short of red and white herrings for Lent. Although he’s abandoned the priesthood, the great, great, great, great grandfather of Aramis is determined his old canonical friends will not go hungry.

Joan of Arc has a vision prophesying the defeat at the Battle of the Herrings and tells her friends the Arquebusketeers. They hatch a plan. While Falstaff is occupied defeating the Duke of Bourbon, they infiltrate the ring of herring wagons. They weren’t expecting Falstaff to get back so soon, but after a belly bump-off between him and Porthos’ great, great, great, great grandfather (Surely one of the great confrontations of European literature) they come away with a barrel of each – enough for the canons and herrings to spare.

The canons come up with a Holy Wednesday procession to use up the surplus, at the same time providing cover for our heroes to escape their deadly enemy, Archibishop Regnault. Meanwhile, Regnault is secretly scheming against their old pal Joan, contriving her capture and trial for heresy and witchcraft.

In a daring rescue, at the last minute the Arquebusketeers replace her at the stake with an effigy, the skin tones of which are cunningly and convincingly achieved using the last of the white and red herrings. Having fallen in love with the young broadswordsman whose derring-do has earned the affection and respect of all except Regnault, Joan gives up visioning for married life in Gascony. ‘Un jour,’ she says as our chums go their different ways, ‘nous reviendrons!’…

Joan of Arc really did have a vision prophesying the Battle of the Herrings, but, sadly, Madame Clément’s account is historically inaccurate, the procession having been initiated over 100 years earlier.

In its Procession des Harengs entry (2002, but based on an article appearing in 1911) the website La France Pittoresque notes the historian Varin tracing its origins to 1300. Plausibly enough, the entry imagines the tradition originating in an anticipatory celebration of Easter, when herring, as daily Lenten fare, could be trodden underfoot with impunity.

Pierre Desportes, in his Historical Review of the Church in France (volume 85, no 215, 1999), explains and dates procession’s demise:

A reformist current began to grow, first noticeable in the 1372 decision that no church ornament should be lent for any theatrical events, even were the subject to be religious. Reform was motivated out of concern for the dignity of the clergy and it was not long before the burlesque Procession of the Herrings, which took place on Holy Wednesday each year, from the cathedral to St Remy, began to seem intolerable, its antiquity notwithstanding… The decision to ban it was taken in 1439.

Thanks

Big thanks to good friends Simon Tepper and Jerry Podmore, who independently sent details of the herring entry in Dumas’ Dictionary of Cuisine and of the Procession pieces by Madame Clément, La France Pittoresque and Pierre Desportes. Big thanks also to Simon Tepper’s neighbour Jack Homer for sharing with him his copy of Dumas’s dictionary.