The hareng saur of the Siege of Paris inspired poems by Cros, Huysmans and Richepin and, with them, the modern French monologue

HARENG SAUR MONOLOGUES

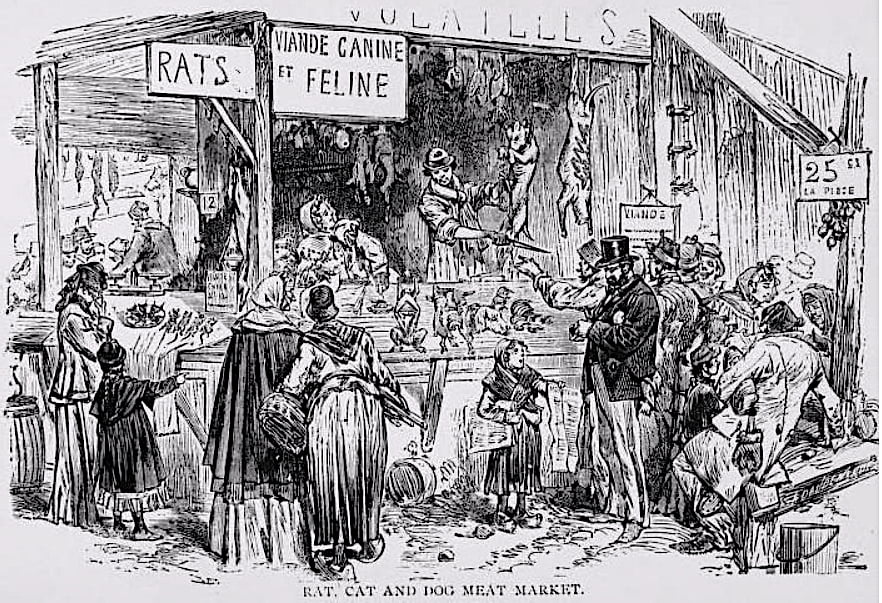

During the Prussian Siege of Paris in 1870, people were famously reduced to eating rats, cats, dogs and worse. A lot of hareng saur or red herring was also eaten: the food of sieges, it’ll last a year or more. Out of what might seem to some as over-familiarity, a strand of French poetry emerged: the modern French monologue or le monologue fumiste. Charles Cros kicked things off with his Le Hareng Saur.

Origins

Its inception was remembered in the autobiography of Mathilde Mauté, 17 years old at the time and recently married to the poet Paul Verlaine. In an apartment on the Boulevard Saint-Germain, her mother played the piano and her step brother hosted a Bohemian group of poets, artists and musicians.

It wasn’t formal, but they’d often invite themselves to dinner, bringing their bread ration and whatever else they’d been able to get hold of. One day, Villiers de L’Isle-Adam turned up with a red herring. Having spent the night on the ramparts, he asked if he could lie down on one of the divans. Charles Cros, who came in while he was asleep, hung the herring on a string above the sleeper’s head; then, while the golden fish swung back and forth, he took a sheet of paper and wrote:

Le Hareng Saur

Once there was a high white wall, bare, bare, bare, etc

The poem first appeared in Cros’ slim volume, The Sandalwood Box (1873), most of which, Mauté says was written at her mum’s during the siege. Others suggest the version written then was an early prose piece, which he developed into the poem, which became famous, learnt at school by generations of children.

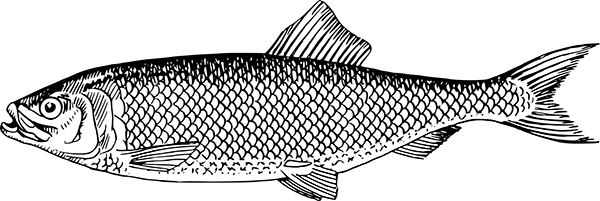

The term, Hareng saur,gets variously translated, partly because it is used for a range of smoke herring products. Cros is specific about its dryness and implicit about its durability. Together with the context of the siege, it all points to it being a hard-salted, hard-smoked red. Cros may have been aware of the figurative use of the fish in English. He later dedicated the poem to his son Guy, born in 1879, to whom quite often he read it at bedtime.

Le Hareng Saur, Charles Cros (1842 – 1888)

The Red Herring

Once there was high white wall – bare, bare, bare,

Against the wall a ladder – high, high, high,

And, on the ground, a red herring – dry, dry, dry.Here he comes and in his hands – dirty, dirty, dirty,

A heavy hammer, a large nail – sharp, sharp, sharp,

A ball of string – big, big, big.So he climbs the ladder – tall, tall, tall,

And bangs in the sharp nail – tap, tap, tap,

Right at the top of the high white wall – bare, bare, bare.He drops the hammer – which falls, which falls, which falls ,

Ties to the nail the string – long, long, long,

And, at the end, the red herring – dry, dry, dry.He climbs down the ladder – high, high, high,

Carries it off with the hammer – heavy, heavy, heavy,

And then, he goes away – far, far, far.And ever since, the red herring – dry, dry, dry,

At the end of that string – long, long, long,

Swings slowly – always, always, always.I made this story up – simple, simple, simple,

To annoy people – so grave, grave, grave,

And entertain the children – little, little, little.

French Text

Le Hareng Saur

Il était un grand mur blanc – nu, nu, nu,

Contre le mur une échelle – haute, haute, haute,

Et, par terre, un hareng saur – sec, sec, sec.

Il vient, tenant dans ses mains – sales, sales, sales,

Un marteau lourd, un grand clou – pointu, pointu, pointu,

Un peloton de ficelle – gros, gros, gros.

Alors il monte à l’échelle – haute, haute, haute,

Et plante le clou pointu – toc, toc, toc,

Tout en haut du grand mur blanc – nu, nu, nu.

Il laisse aller le marteau – qui tombe, qui tombe, qui tombe,

Attache au clou la ficelle – longue, longue, longue,

Et, au bout, le hareng saur – sec, sec, sec.

Il redescend de l’échelle – haute, haute, haute,

L’emporte avec le marteau – lourd, lourd, lourd,

Et puis, il s’en va ailleurs – loin, loin, loin.

Et, depuis, le hareng saur – sec, sec, sec,

Au bout de cette ficelle – longue, longue, longue,

Très lentement se balance – toujours, toujours, toujours.

J’ai composé cette histoire – simple, simple, simple,

Pour mettre en fureur les gens – graves, graves, graves,

Et amuser les enfants – petits, petits, petits.

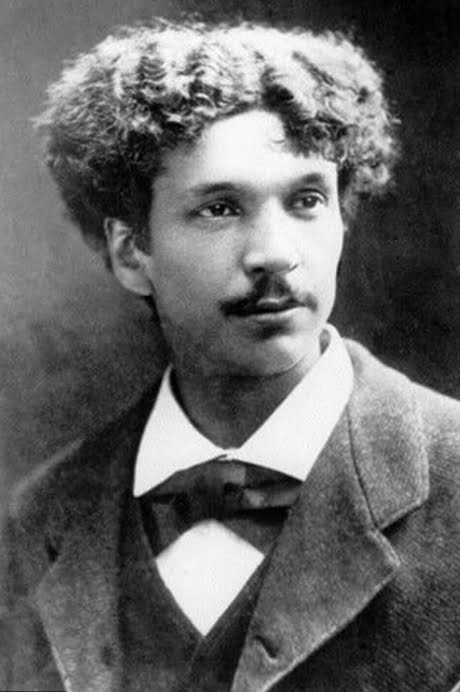

Charles Cros and Le Hareng Saur

A poet and inventor, in 1867 he developed a theoretical method of colour photography a year before Ducos du Hauron patented his. Ten years later he came up with the Paleophone, a phonograph, eight months before Edison patented his method.

He was a key member of Le Cercle des poètes zutique aka Les Zutistes (from the French expression zut! as in Zut alors!). It included fellow poets Verlaine and Rimbaud, the composer Ernest Cabaner and illustrator André Gill and was established in 1871 out of a nostalgia for the comradeship of the Siege.

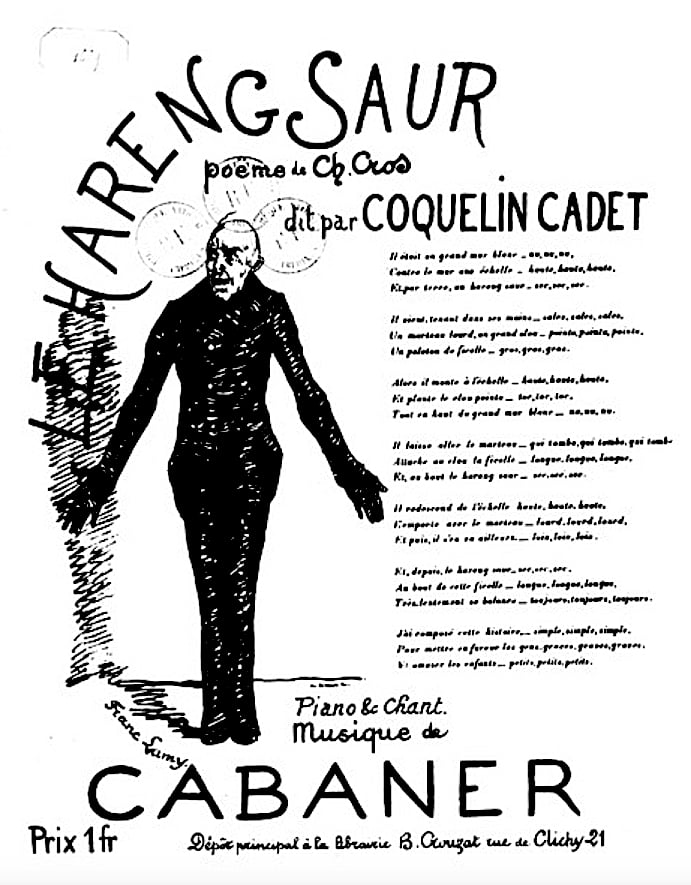

Cabaner set Le Hareng Saur for performance as a musical monologue and Cros’ own delivery was celebrated by those who witnessed it. The performer Coquelin Cadet made it famous:

The monologue is one of the most original forms of contemporary entertainment; an extraordinarily Parisian ragout, in which the French farce smoker and the musical saw meet the shock of America; in which the implausible and the unexpected gambol playfully and peaceably around that which is serious; in which reality and the impossible find their bases in cold-eyed fantasy … I speak of that monologue to which Charles Cros gave birth, I myself, if I may say, playing midwife; that monologue, that oddly-shaped child, whose earliest stutterings were le Hareng Saur … In that moment I saw the dawn of the modern monologue. Never have I been so curiously impressed as when, with the gravity of a man reciting Châteabriand or Lammenais, Cros delivered his incomparable Hareng Saur. Little did I imagine this small fish would grow so large, that it would be so relished by the crowds of Café-Concert goers, that it would so charm that ocean they call Paris.

You can almost feel the reluctance to pay Cros any royalties, but it led to a falling out. I’ve never been one for actors performing poetry: the way Cros performed it seems great. Coquelin Cadet, however, left line by line instructions as to how he felt it should be delivered, which open up on the world of Café Concert monologue performances. You might need to play with the translation a little, but it might be something you’d like to try at home.

Coquelin’s Instructions for the Delivery of Le Hareng Saur

Announce Le Hareng Saur in a strong voice. Do not move; be absolutely still. When giving the title, the audience should feel that it is a black line, standing out against a white background.

Il était un grand mur blanc — nu, nu, nu,

Once there was high white wall – bare, bare, bare,

One senses the straightness and solidity of the wall, its boring monotone, so break the monotony: lengthen the sound of the third nu, it makes the wall bigger, almost giving the audience the experience of its dimension.

Contre le mur une échelle — haute, haute, haute,

Against the wall a ladder – high, high, high,

Use the the same intent and intonation as for the first line and, to impart the idea of height, bring in a falsetto (out of the blue) on the last haute, which will make you laugh, entirely in keeping with the fantasy.

Et, par terre, un hareng saur — sec, sec, sec.

And, on the ground, a red herring – dry, dry, dry.

Point to the ground and say hareng saur with a sad expression which draws attention to this unfortunate herring, the voice, of course, very dry for the three adjectives, sec, sec, sec.

Il vient, tenant dans ses mains — sales, sales, sales,

Here he comes and in his hands – dirty, dirty, dirty,

Support the voice and let us feel the same rhythm in all the stanzas that was in the first. He is our character, we don’t know who he is. Let us see, show us this He, who moves you, the actor, and paint the disgust at a man who never washes his hands in you sales, sales, sales.

Un marteau lourd, un grand clou — pointu, pointu, pointu,

A heavy hammer, a large nail – sharp, sharp, sharp,

Lower your shoulder with the weight of a hammer which is too heavy for you, and show the audience the nail, pointing your index finger at them and pressing the pointu, pointu, pointu, so that the nail makes its entrance into their attention.

Un peloton de ficelle — gros, gros, gros.

A ball of string – big, big, big.

Spread your hands, moving them away from your hips with each gros, gros, gros. He is laden, a heavy hammer, a large sharp nail, an enormous ball of string, this is no small thing, it is necessary to show the burden under which this poor He labours.

Alors il monte à l’échelle — haute, haute, haute,

So he climbs the ladder – high, high, high,

Same game as for the earlier haute, the high note at the end, this insistence can make you laugh.

Et plante le clou pointu — toc, toc, toc,

And bangs in the sharp nail – tap, tap, tap,

he gestures of a man driving in a nail with a hammer, giving voice to the strength of each knock without changing the sound.

Tout en haut du grand mur blanc — nu, nu, nu.

Right at the top of the high white wall – bare, bare, bare.

Keep the voice strong, lengthen the last nu again, making a flat hand gesture to show the indifference of the wall.

Il laisse aller le marteau — qui tombe, qui tombe, qui tombe,

He drops the hammer – which falls, which falls, which falls

,

Lower the pitch by degrees to convey the falling of a hammer. Look at the audience at the first qui tombe, at the ground for the second, and at the audience again for the third, waiting for the effect which must come.

Attache au clou la ficelle — longue, longue, longue,

Ties to the nail the string – long, long, long,

Lengthen each longue by degrees and let the last to be of immense length, a wrong note in the middle of the final intonation, creating a very comical effect.

Et, au bout, le hareng saur — sec, sec, sec.

And, at the end, the red herring – dry, dry, dry.

Allow an increasingly pitiful air to the third sec.

Il redescend de l’échelle — haute, haute, haute,

He climbs down the ladder – tall, tall, tall,

Same game as before, when going up, only going down with the haute, the first in falsetto, the second pitched in the middle, the third pitched low. Musical.

L’emporte avec le marteau — lourd, lourd, lourd,

Carries it off with the hammer – heavy, heavy, heavy,

Bend under the weight of it all. You are broken, you can’t take any more, don’t forget how heavy this hammer is.

Et puis, il s’en va ailleurs — loin, loin, loin.

And then, he goes away – far, far, far.

Let each loin get further and further away, when you come to the third, you will be able to put your hand to your brow shielding your eyes from the light so you can see Him in the distance and, after having spotted Him there, you will say the last loin.

Et, depuis, le hareng saur — sec, sec, sec,

And ever since, the red herring – dry, dry, dry,

More and more pitiful each time.

Au bout de cette ficelle — longue, longue, longue,

At the end of that string – long, long, long,

Lengthen each longue with a very melancholy air, always with the wrong note; don’t worry, it’s a [musical?] saw.

Très lentement se balance — toujours, toujours, toujours.

Swings slowly – always, always, always.

Very sad. And make a swinging gesture with each toujours. Finish the line well, lowering your voice for the third toujours, because the story is over. The last stanza brings only the consolation of a postscript for the audience.

J’ai composé cette histoire — simple, simple, simple,

I made this story up – simple, simple, simple,

Press on simple, so that the audience says to itself, Oh! Yes! Simple!

Pour mettre en fureur les gens — graves, graves, graves,

To annoy people – so grave, so grave, so grave,

Very stuffed shirt; let’s feel those stiff white ties of the civil servants who don’t appreciate such jokes.

Et amuser les enfants — petits, petits, petits.

And entertain the children – little, little, little.

With a very kindly voice, gradually lowering your hand to each little, indicating the height and age of the children. Bow and leave quickly.

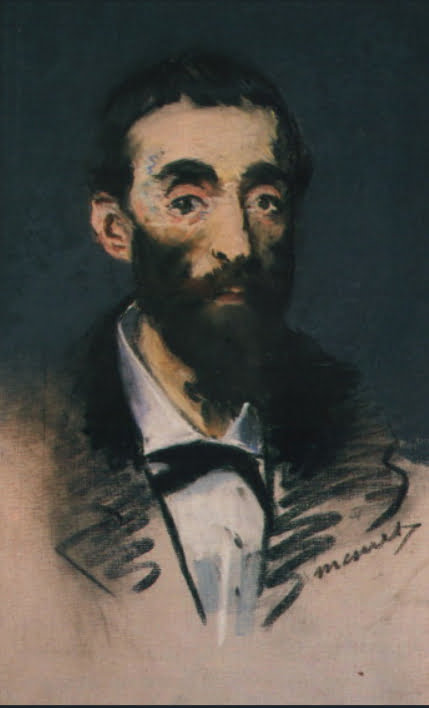

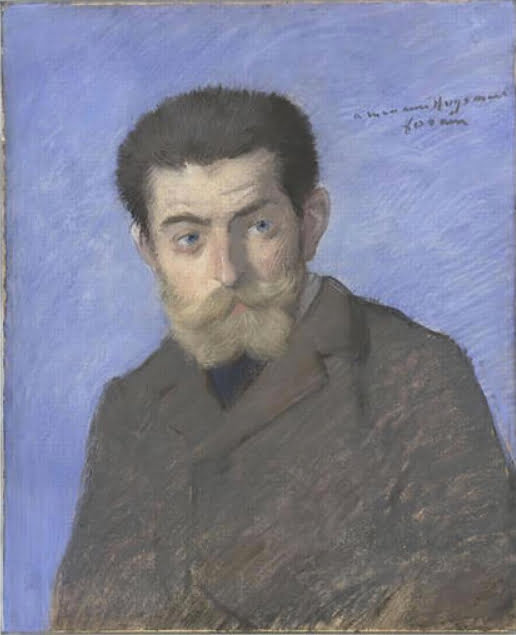

Le Hareng Saur, Joris-Karl Huysmans

The year after Cros first published his Hareng Saur, J K Huysmans published a prose poem of the same name in his first, Baudelaire-influenced slim volume Le Drageoir des Épices (1874, The Spice Box). It isn’t known whether he was aware of Le Cros’ poem, although it is most likely that he was. It wasn’t performed as a monologue – he saw it as a still life – but it is clearly written as a performative piece. It seems to be a deliberate response to Cros, a demand to look at the smoked fish as an example of the extraordinary.

The intensity of the colours he discovers also suggests the highly smoked red herring. Huysmans, who worked as a civil servant, was called up during the Franco-Prussian War, but was invalided out with dysentery. In his writing career, he moved from naturalism, through decadence to Catholicism and is most famous for A Rebours (Against Nature, 1884) and Là-Bas (Down There, 1891).

Le Hareng Saur, JK Huysmans (1848 – 1907)

The Red Herring

Your gown, O Herring, it is the palette of setting suns, the sheen of old copper, the burnished gold of Cordovan leather, the sandalwood and saffron shades of autumn!

Your head, o herring, blazes like a golden helmet, and your eyes are like black nails driven into rings of copper!

All the sad and dreary colours, all the shining, joyful colours, by turn they dull and they illuminate your gown of scales.

Beside to the bitumens, the Judean soil, the Cassel earth, burnt umbers and Scheele’s greens, the Van Dyck browns and Florentine bronzes, the tints of rust and dead leaves bring out the radiance of the green-tinged golds, the yellow ambers, stonecrops, brown ochres, chromes and iron oxides!

O shimmering and smokey, when I behold your coat of mail, I see the works of Rembrandt, I can picture his superb heads, his sunlit flesh, his jewels flickering on black velvet, I can picture his shafts of light in the dark, his trails of golden dust in the shadows, his bursts of sunlight beneath the vaulted blacks!

French Text

Le Hareng Saur

Ta robe, ô hareng, c’est la palette des soleils couchants, la patine du vieux cuivre, le ton d’or bruni des cuirs de Cordoue, les teintes de santal et de safran des feuillages d’automne!

Ta tête, ô hareng, flamboie comme un casque d’or, et l’on dirait de tes yeux des clous noirs plantés dans des cercles de cuivre!

Toutes les nuances tristes et mornes, toutes les nuances rayonnantes et gaies amortissent et illuminent tour à tour ta robe d’écailles.

A côté des bitumes, des terres de Judée et de Cassel, des ombres brûlées et des verts de Scheele, des bruns Van Dyck et des bronzes florentins, des teintes de rouille et de feuille morte, resplendissent, de tout leur éclat, les ors verdis, les ambres jaunes, les orpins, les ocres de rhu, les chromes, les oranges de mars!

Ô miroitant et terne enfumé, quand je contemple ta cotte de mailles, je pense aux tableaux de Rembrandt, je revois ses têtes superbes, ses chairs ensoleillées, ses scintillements de bijoux sur le velours noir; je revois ses jets de lumière dans la nuit, ses traînées de poudre d’or dans l’ombre, ses éclosions de soleils sous les noirs arceaux!

L’Hareng Saur, Jean Richepin (1849 – 1926)

Richepin apostrophises the Le, but this creeping onset of modernity is not the reason for translating the title of his poem as The Bloater. In addressing the smoked herring, he refers to its soubriquet cocasse (funny nickname) which seems a reference to bouffi or bloater (see entry, Hareng Saur). In English there are traditional bloaters (an interchangeable term for red herrings) and Yarmouth bloaters (the milder-cured creation of the railway age).

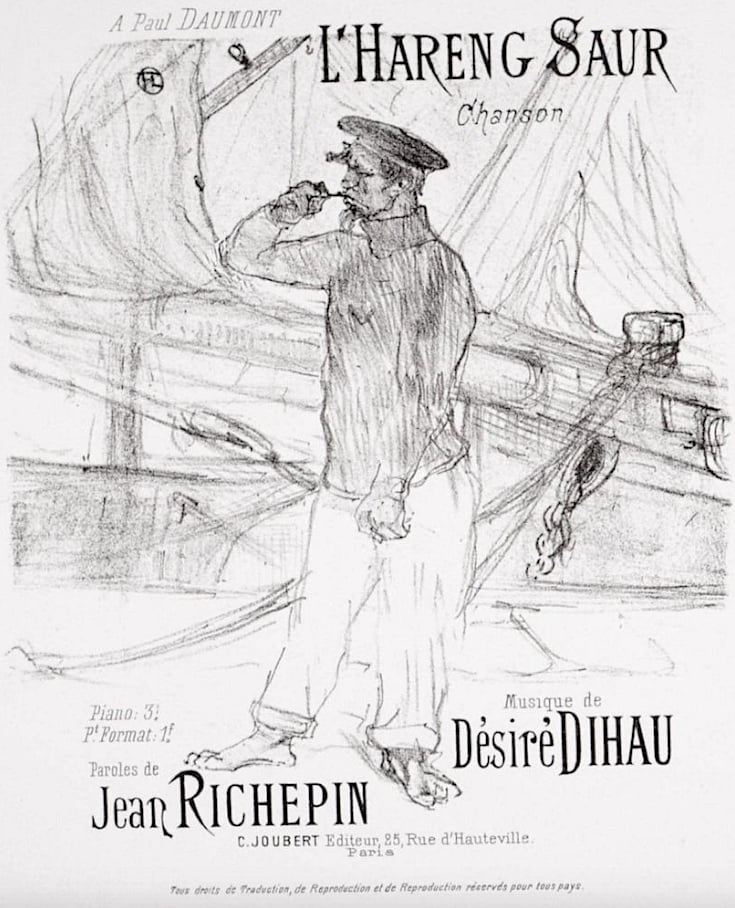

The poem was published in 1886 in Richepin’s collection Le Mer and was intended from the start to be a monologue for the market opened up by Cros, Cabaner and Coquelin. In the Franco-Prussian War, Richepin had fought as franc-tireur or free-shooter, an irregular. He’d worked with André Gill on a play, The Star, in 1873 and had collaborated with Cabaner, who died in 1881. His first volume of poems, La Chanson des Gueux (1876, The Beggars’ Song) saw him imprisoned for offending public decency.

The composer Désiré Dihau set L’Hareng Saur, the sheet music for it illustrated by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Bloater

No blushes please, no carcass-shame,

Old pal o’ mine they call the bloater.

Guard that crazy name they gave you

Like a treasure.Let ’em laugh, that sainted crew –

Fine fellahs all, etcetera.

For ugliness you’re nowhere near

Their la-di-dah!For all those blessed airs and graces,

How long it takes to scrub ’em bright!

Flesh as limpid as the air

And ermine white.Tubs await them every morning

As they tumble from their bedding:

Hands appear, all soap and lather,

For the scrubbing.That precious skin of theirs is like

A blown-up bladder dubbed with lard:

Give me the leather riches of

our old tarp.It’s just anaemia, you know,

That grants that mannered sheen like silk,

That pretty-as-a-petal pink,

Bathed in milk.Is your hide clean or not? Who cares?

Its grain is noble to a fault:

Weather-beaten, it won’t shun

The curer’s salt.Pulling on those offshore breezes,

Cooking, dreaming in the smoker,

While, beneath, those horses charge

With blood like silver.Kit, caboodle meld and settle

In the patina of time:

Strange metals, rare tones

That gleam and shine;And proudly on your solid neck,

That old phizzog: its monkish cast

Holds my gaze, as if a bust

Of gold and brass.

French Text

L’HARENG SAUR

Ne rougis pas de ta carcasse,

Toi, vieux, qu’on nomme l’hareng saur.

Garde ce sobriquet cocasse

Comme un trésor.

Laisse rire ces bons apôtres.

Nos beaux messieurs à tralala.

Car tu n’es pas si laid qu’eux autres.

Bien loin de là!

Ils font les fiers avec leur mine.

Mais c’est l’astiquage qui rend

Leur corps aussi blanc qu’une hermine

Et transparent.

Tous les jours avec de l’eau douce

Ils se lavent au saut du lit

À force de savon qui mousse

Et qui polit.

Ils ont la peau comme une espèce

De baudruche passée au lard.

J’aime mieux ta basane épaisse

Comme un prélart.

Car c’est avant tout la chlorose

Qui donne à leur teint ce reflet

Et fait ces pétales de rose

Trempés de lait.

Toi, que ton cuir soit propre ou sale,

Qu’importe ! Il est d’un fameux grain,

Il se tanne au soleil, se sale

Dans le poudrain,

Se culotte aux souffles du large,

Se cuit même dans ton sommeil;

Mais dessous court au pas de charge

Un sang vermeil.

Et tout cela, mon camarade,

Hâlé, fumé, roux, fauve, brun.

Le soleil, l’eau, l’air de la rade,

Le vent, l’embrun,

Tout cela se fond et s’arrange

Avec la patine des ans

En un riche métal étrange

Aux tons luisants ;

Et, dressé sur ton col robuste,

Ton vieux museau de mathurin

Resplendit pour moi comme un buste

D’or et d’airain.

Translations and Acknowledgements

Firstly, I’d like to thank my good friend, the artist and writer Isis Olivier, who helped with the translations of all three poems/monologues. She is the herripedia’s Official Advisor on French Translation. I’d also like to thank another good friend, Jerry Podmore, who spotted the Toulouse-Lautrec illustration for Richepin’s L’Hareng Saur in an antique shop somewhere in France and who then alerted me to the existence of this third monologue.

In the research for this entry, I read and would recommend Laughing Matter: Charles Cros, From Paléophone to Monologue (Nottingham French Studies, 2020) by Greg Kerr and Chapter 1 of L’art de parler pour ne rien dire, Le monologue fumiste fin de siècle (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2005) by Françoise Dubor. My French can be a bit slow, but when I have time, I will go back to this excellent book and read the lot.

See also

- AQUINAS, ST THOMAS

- BLOATER

- BRITTEN

- CALLER HERRIN’ (FILM)

- CALLER HERRIN’ (SONG)

- DRIED HERRING

- DUMAS ON HERRING

- EYVIND SKÁLDASPILLIR

- HARENG SAUR

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- KIPPER

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- MARTYRED SAINT

- MONKEY BUSINESS

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- OLIVIER, LAURENCE

- PARA HANDY

- PICKELHERING

- PROCESSION OF THE HERRINGS

- RED HERRING

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- RING NET: WILL MACLEAN

- ROLLMOPS & BISMARCKS

- SHOALS OF HERRING, THE

- SINGING THE FISHING

- SMOKEHOUSE TALES: GERRY SKEWS

- SMOKEHOUSE TALES: WILL BUCKENHAM

- SUFFERING SALTWORKERS OF SHIELDS

- SWIFT, JONATHAN

- WHEN HERRINGS LIVED ON DRY LAND

- WILLIAMS, WILLIAM CARLOS: FISH