An account of the herring’s long misunderstood migratory travels, the pursuit of abundance and factors that enable or would inhibit this

MIGRATION & MOVEMENT

The general diagrammatic principle of fish migration is the triangle.

First there is a denatant journey between the spawning ground at point A and the nursery ground at point B – eggs and larvae drifting or swimming with the current. Recruitment sees the surviving young fish swim from B to the adult feeding ground at point C.

The third side of the triangle is a contranatant journey (against the current) from C back to the spawning grounds at A. The fish then take a denatant journey back to C, then go back and forth contra- and denatantly until the grim reaper intervenes.

Speed & Distance

Fish such as salmon, cod and herring can travel at speeds of up to three times their length per second, which works out at around 1.5 knots for a 25 cm herring. In consequence of the three times principle, the largest fish, as the strongest swimmers, will always be at the front of the shoal.

This may explain the East Anglian folk belief that shoals were led by a ‘demon herring’ or even a shad.

The migratory journey of the Norwegian spring herring stands at 1,800 miles. Although elsewhere its journeys are shorter, as a whole, Atlantic herrings make the longest migrations among the Clupeidae.

Movement

The dorsal fin allows the fish to move in a straight line and to stabilize in body turns. The anal fin allows it to raise and lower its head and move the tail end in the opposite direction to the front. Experimental removal of the anal fin apparently leaves herrings unable to lower their heads at all.

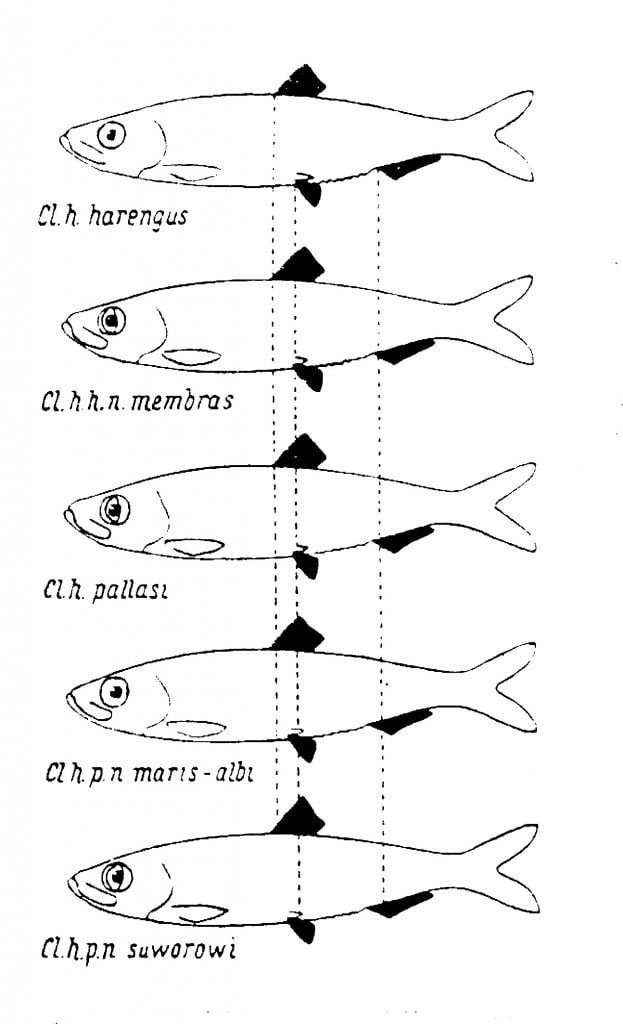

The distance between dorsal and anal fins in the Clupeidae is significant in sustaining the possibility of longer migrations and is consequently greatest in the Atlantic herring. Body pigmentation is also apparently strongest in the more extensively migrant.

Abundance

Migration is an adaptation towards abundance, it being unlikely that there will be enough food on one ground to support both immature and mature fish belonging to large populations. The pursuit of abundance leads to abundant stocks and, in fishery terms, commercial importance.

The abundance of stocks in absolute terms (if over-fishing is removed from the equation) is determined both by the migration’s range and its duration, Norwegian and Murman herring populations being particularly large.

The basic migratory triangle is complicated by the use of different feeding grounds. In Clupeidae (1952), basing his account on the work of Rass (1939) and Marti (1941), Svetovidov tells the story the Murman herring’s travels:

Larvae from the spawning grounds near the Lofoten and Vestvogoy Islands drift northward and eastward along the North Cape branch of the North Atlantic Drift, passing the littoral stage of development at the age of 4 – 5 months near the shores of Finnmark and Murman. Following their metamorphoses, the fry actively distribute themselves through the central and eastern parts of the Barents Sea via the sea currents. During the summer, during their second and third year of life, the herrings have the broadest range throughout the Barents Sea, while during the winter, while moving to central and western regions of the sea, these herrings occupy a more limited range. Commencing with the fourth year of life, their range shifts to the west. In the summer, herrings of this age spread eastward, while in the fall and winter they move westward and approach the coastal regions, entering the inlets of the Murman Coast in mass during certain years. The maturing herrings, starting in the fall and during the winter, gradually leave the western part of the sea and move towards the spawning grounds, initially breeding in the northern parts of the spawning grounds. Following first spawning, 5 and 6 year old herrings leave the spawning grounds for the western part of the Barents Sea, apparently staying along its border with the Norwegian Sea. When they spawn for the second time, herrings (8 year-olds and over) reproduce in the more southerly parts of the spawning grounds and, following spawning, travel northward to Spitsbergen.

Electrical Impulses

As a fish of such quasi-miraculous properties, it is not surprising to discover that Svetivodov numbers it among those with a finely developed network of cutaneous nerve endings. They appear to respond to the natural electrical currents that occur in the sea.

In experiments conducted by the Russians in the 1940s, the Atlantic herring reacted very sensitively to artificially introduced electrical impulses, orienting themselves in the direction of the anode and moving toward it when a direct current field is set up.

In this way, Svetivodov noted, shoals of fish may be held in one place or moved at will. The practical applications of this technology aren’t explored, but may not be consistent with a sustainable fishery.