On the spawning preferences of the herring, together with a list of the spawning grounds for the main Eastern Atlantic populations

SPAWNING

Shoals of herring gather at the edges of their spawning grounds before moving into shallow waters to lay and fertilize the eggs. Shallow is a relative term. Near the shores of Greenland, this can be less than 1m, but in some oceanic, offshore populations it occurs at depths of up to 200m.

Most inshore spawning is on banks between 15 and 20m deep. Cossar Ewart (see Racial Theory) first described spawning behaviour in the 1880s, from observations of herrings in tanks. The female deposits her eggs in ribbons, which sometimes gather into little cone-shaped heaps. Males release milt into the water around the females. There is no indication of pairing.

Harden Jones (Fish Migration, 1968) lowered hydrophones into or close to spawning shoals and concluded that, unlike the cod – which by all accounts is a noisy reproducer – and despite its communicative squeaking or farting from the swim bladder, sound plays no part in a herring’s sexual activity.

Egg Laying

The herring is unusual amongst pelagic species of the Atlantic in having demersal eggs – laid on the bottom rather than floating. They are between .9 and 1.5mm in diameter, heavier than water and adhesive, deposited in a sticky mass and in large numbers. The adhesive is produced by an ovarian secretion from granulosa cells.

A female generally lays between 10,000 and 60,000 eggs, although figures as high as 95,000 have been recorded in the estuary of the River Schley. The most cold-loving of all the herrings, Clupea (harengus) pallasii n maris-albi spawns at Oº C, but the varieties of the Atlantic herring spawn at between 5º and 14º C, with hatching taking approximately 22 days at the lower, 8 – 10 days at the higher end of that range.

They avoid silt or sand-silt beds and tend to lay the eggs on areas with small stones, gravel, broken shells, sand grains or at least seaweed. These individual beds can be quite small within the spawning grounds.

Upwelling water can sometimes take the milt away from the eggs, disrupting fertilization, and if this happens over a broad area it can have severe effects on the size of a particular year group. Beam trawling, scallop dredging and the habit of dumping industrial waste at sea all threaten the herring’s spawning grounds and have led to the loss of a number of the sites.

Cod and haddock have a noted taste for herring eggs. Fishing for full herring – when they are at their tastiest – clearly doesn’t improve matters. They seem to like hemlock branches – the Sitka tribe in Alaska traditionally harvest the spawned eggs of Clupea pallasii with them, although there is conflict with the fishery regulators on the practice. The method does suggest a way forward could be found in compensatory interventions to increase the number and size of suitable sites.

Salinity

Although the species tolerates a wide range of salinity, the individual varieties are very sensitive. This has been observed in the population of spring spawning herrings in the northern North Sea plateau, where normal levels of salinity (33 – 34%) on the Viking Bank, for example, can be affected by low saline water coming from the Baltic (below 30%) or higher saline water from the Atlantic (over 35%). On these occasions the herring leave the coastal areas and spawn further out to sea.

Populations of the Baltic herring, cut off from the sea, have adapted to fresh water conditions, but, in experiments where eggs are transplanted from sea to fresh water, even though they themselves develop normally, the hatched larvae die within a day.

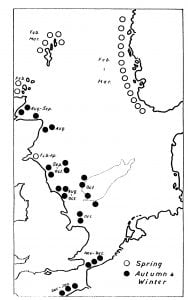

Spawning Groups

The spawning groups are broken down by geographical location and by season, although some confusion has occurred in herring studies through different scientific nationalities adopting different seasonal definitions.

Oceanic Spawners

Greenland: Small numbers on the west and east coast and in the Denmark Strait, spawning in August and September, probably related to Icelandic summer spawners.

Iceland: Spring spawners in the Selvogsbanki area, off the south west coast; summer spawners in the same area, further west at Faxafloi and south east at Horna Fjord.

Faroes: Spring spawners (March and April) to the south and south east of the Faroe Islands.

Hiberno-Caledonian: Spring and summer spawners in the Minch and on the continental shelf west of the Hebrides; also possibly near the Flannan Isle.

Shetlands, Orkneys and the Scottish coast: Spring spawners to the north and west of the Shetlands, to the west and east of the Orkneys, off the coasts of Sutherland and Caithness, Fife Ness and Berwick.

Northern North Sea Plateau: Some spring spawners on the north east edge of the plateau and on the western edge of the Norwegian Rinne.

Norway: Off the south west coast between Egersund and Bergen and between Stadt and Kristiansund (the Norwegian spring herring); off Lofoten and Vesterålen on the northern coast (the Murman spring herring).

North Sea Spawners

Buchan: Northern North Sea summer and autumn spawners with grounds off Copinsay in Orkney, in the Moray Firth and on the Turbot, Aberdeen, Montrose and Berwick Banks.

Dogger: The autumn spawning stock on the Dogger Bank has collapsed. Other grounds for this group lie off Whitby and Scarborough, off the Humber, the Wash and the north east coast of Norfolk.

Downs: Winter spawners, also referred to as Channel or Southern Bight herring, from the Gabbard Light Vessel of the East Anglian coast to Pointe d’Ailly to the west of Dieppe.

Other Main Groups

The Southern Entrance to the Irish Sea: Winter/spring spawners, related to the Hiberno-Caledonians.

The Danish Straits: A complex of mixed populations including winter herrings of the Kattegat, autumn herrings of the north east Kattegat, autumn herrings of the southern Kattegat and the Sound and spring herrings of the Skagerrak, Kattegat and the Belt. They are variously related to Oceanic, Bank and Baltic herrings.

Baltic: Spring spawners normally close to the shores in the eastern Baltic and the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland; autumn spawners closer to the open sea.

North America: Offshore oceanic spring spawners; spring and autumn spawners in the Gulf of St Lawrence, at Grande-Rivière in Québec and near the western coast of Nova Scotia; spring and late summer spawners in the Bay of Fundy; late summer / autumn herrings to the south of Cape Cod.