A history of canning, the derivation of ‘can’, sardines, pilchards, herrings and sprats, the great nations and the Great Sardine Litigation

CANNING

The initial imperative that led to canned food was military. As C.L. Cutting points out in Fish Saving (1955), Marlborough’s army at Blenheim in 1704 numbered only 54,000 men, who could almost live off the land. Napoleon invaded Russia in 1811 with over a million, and a highly organized food commissariat was required.

Nicholas Appert

In 1795, a prize of 12,000 francs was offered by the French Directory for a means of preserving not just food, but a significant proportion of original taste and texture. Nicholas Appert won the award in 1809 for a bottling process.

The Book for All Households, or the Art of Preserving Animal and Vegetable Substances for Many Years, which he published in 1810, was translated into English the following year. Appert was supplying the French government by 1814 and preserved fish was among the products.

The Dutch were already selling salted, juniper-smoked potted salmon in tinned-iron boxes and in 1810, the British merchant Peter Durand speculatively patented a tin-plate container, which could be adapted for Appert’s new technique.

When applying for an American patent in 1818, Durand coined the term tin canister, from the Greek word κάναστρου, meaning a basket of reeds – something regularly used for holding foodstuffs in the early C19th.

The Americans & the French

From 1819 Thomas Kensett and Ezra Dagget began preserving seafood in New York, later extending the business to Baltimore. They patented an improvement to the canning process in 1825. From the early 1820s William Underwood was preserving salmon, lobster and other products in Boston.

Canisters became cans in 1839, an abbreviation introduced by Underwood’s book-keepers.

The Maine or Brunswick Sardine, first successfully canned in 1876 by Julius Wolff and Herman Ressing in Eastport, Maine, is an immature Atlantic herring, just as European sardines are immature pilchards. All sardines from the North American Atlantic coast are herrings that were renamed in order to break into the market developed from the 1820s by Joseph Colin in the French Atlantic port of Nantes.

The French sardine canneries spread to Brittany, but then, in search of more reliable supplies, to Portugal and Morocco. Wolff and Ressing’s breakthrough led to a rapid expansion of canneries along the coasts of Maine, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

In 1871 immature menhaden, a gastronomically unpopular species of the Clupeidae, were marketed in New Jersey as shadines, but it didn’t catch on.

In 1874, A.K. Shriver of Baltimore had come up with a steam kettle, using superheated water, which by maintaining pressure outside the can prevented bursting. In 1900, Joseph Sutton Clark invented the can opened with a key, but it wasn’t until 1932, in Blacks Harbour, New Brunswick, that Henry T. Austin developed the iconic sardine tin with a detachable key.

Ring-pulls have now superseded this wonder of twentieth century technology, but Blacks Harbour is home to Connors Bros, the largest sardine cannery in the world, a business begun with fruit, clams and scallops in 1885. It was the Brunswick Sardine and a commitment to mechanisation that transformed the fortunes of Lewis and Patrick Connors.

When is a Sardine Not a Sardine?

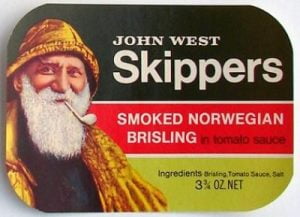

The Norwegians moved into booming market for tinned sardines, creating a product using smoked juvenile herring and sprats. Early on, they developed a relationship in the UK with the Tyneside grocery entrepreneur Angus Watson.

Watson had been shown a can that had been sent to his employer at the time. He doesn’t date the incident, but it seems to have been in the late 1890s. The fish, though crudely packed, were dainty and attractive, he wrote later. They were cheaper than French or Portuguese sardines. Watson suggested that it might be worth going over to see the Norwegian canners, but his employer wasn’t keen. Watson bought a frock coat and a silk hat and went himself.

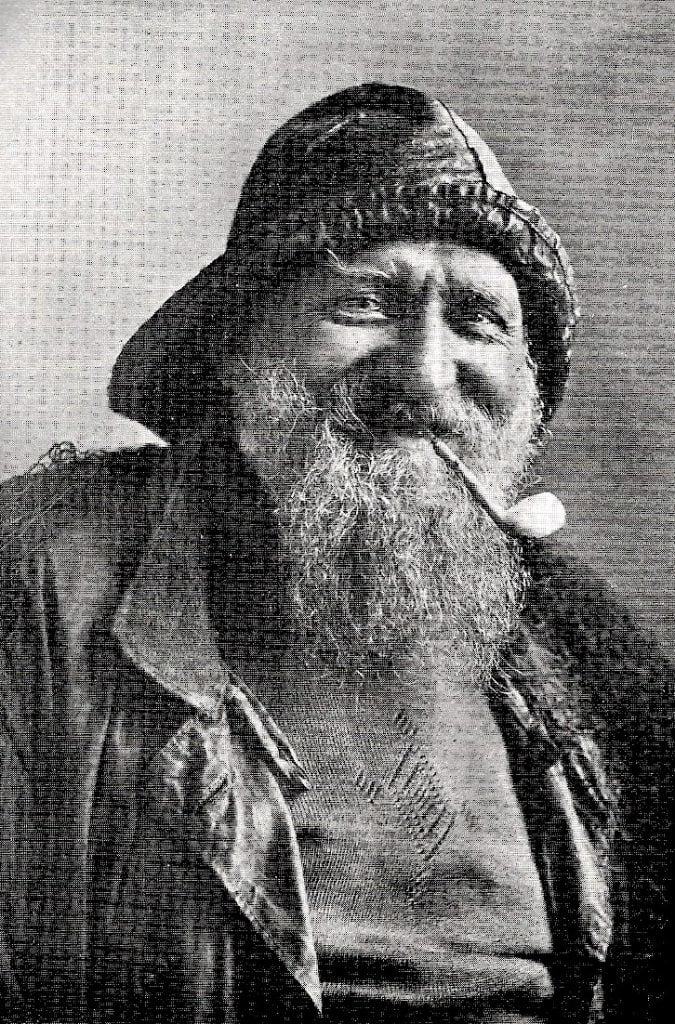

Helping the Norwegians develop their production capacity, by the early 1900s he had his own Tyneside business and was putting his mind to marketing the tins for which he was the sole international representative. Together with a colleague he hit upon Skipper as a brand name and, on a visit to London, saw what was to become the brand image in a photographer’s window in Oxford Street.

Meanwhile, in Stavanger, the Norwegians were developing their production for the international market – King Oscar, Bjelland & Co, Atlas, Saga and many other brands. The Norwegian Canning Museum in Stavanger has a collection of over 30,000 different sardine can labels.

Everything was going swimmingly. Too swimmingly. The French went to court in a number of countries to insist that a canned sardine could only be a pilchard (Sardina pilchardus). The Great Sardine Litigation lasted from 1911 to 1915 and though the position has its illogicalities (see Sardines) the decisions went their way. They tried to extend their success beyond Europe, but gave up – North American East Coast sardines are still herrings. Elsewhere they can be a range of other clupeid species. But in Europe, since 1915 Norwegian canned juvenile herrings have been sold as Sild (herring) or Brisling (sprats).

More recently, following EU guidelines, anything of a sardine-type can be sold as a Sardine if labelled with its actual species – so John West, which was formed in 1961 out of a merger of three companies including Angus Watson & Co, is now labelling its product Sardines (Sprattus sprattus). But not in Australia, where they are Wild Scottish Sardines.

Canned Herring

Adult pilchards are still canned as pilchards, although they’ve never really achieved the popularity of sardines. And on the slab at the fishmongers, they’re mostly now called sardines, letting the Great British Public know that this is what they were eating from the grill at that Portuguese beach restaurant. But you rarely see canned adult herrings these days. Another North East England firm, Tyne Brand, was quite active in production, but again, they never really captured the public imagination.

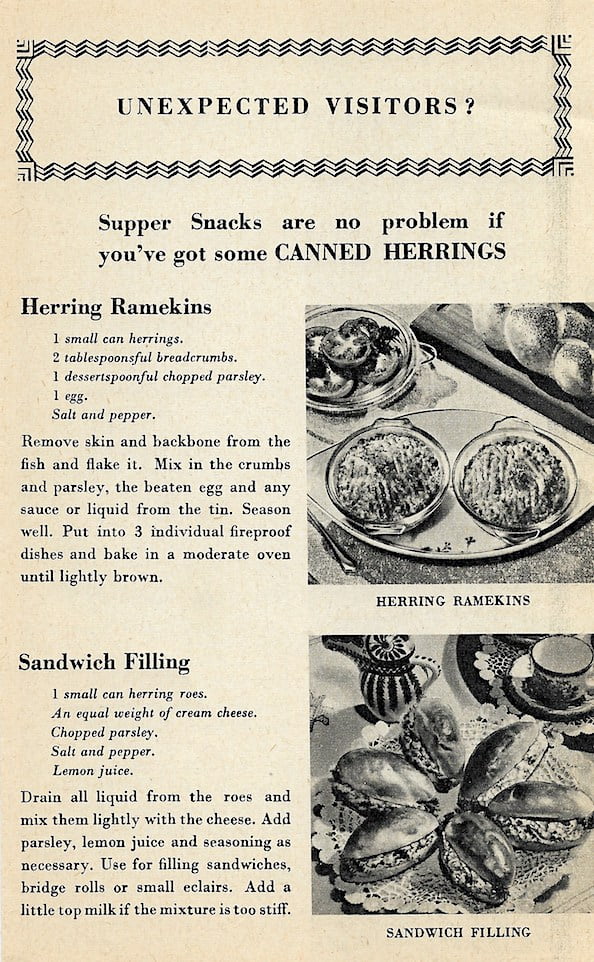

In its Have Herrings post-war promotional recipe leaflets, the Herring Industry Board were clearly pushing canned herrings, giving feature pages for them. Having lost the huge Russian and German markets that had sustained the heyday of the British herring fisheries, there was an increasing desperation in their attempts to encourage a compensatory home market. The housewife wanted convenience. What could be more convenient that a tin of herrings? They are just as tasty as fresh herrings, they assured their June readers. But they weren’t buying fresh herrings either.

Meanwhile, the Norwegian Canning Museum in Stavanger is one the world’s truly beautiful museums and well worth a visit. It’s been closed for a while as part of a Stavanger cultural redevelopment, which is going to see a new printing museum, too – an interesting pairing, given their sardine label extraordinary collection. It reopens in June 2021!