HERRING INDUSTRY BOARD

A child of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, the Herring Industry Board was shaped by his Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries the Scottish Unionist Walter Elliot, MP for Glasgow Kelvingrove. The Herring Industry Act that created it was passed on 24th May 1935. In failing health MacDonald resigned on 7th June and Elliot became Stanley Baldwin’s Secretary of State for Scotland, but retained a guiding interest in the Board.

The Herring Industry Board had been established to rebuild a fishery which had caught and sold staggeringly large numbers in 1913, but which, by the 30s, was in serious decline. It tried hard.

The herring fishery was seen by the politicians as a largely Scottish concern. A 1937 parliamentary debate on the Board’s work was held in Scottish parliamentary time and Pierse Loftus, Conservative MP for Lowestoft prefaced his contribution, I feel that I ought to apologise, as the representative of an English constituency, for rising at all in a Scottish Debate, but Lowestoft is the largest herring port in Great Britain, and the Lowestoft boats land double the quantity of herring landed at any other port in Great Britain, and that is my reason for intervening.

It was not the size of the port, though, or the catch of the boats, but the size of the fleet and the scale of involvement in the curing trade. As the Scottish boats followed the herring, the Scottish curers followed the fleet, contracting the Scottish herring lasses to follow it with them.

Walter Elliot opened the debate, while his fellow Unionist Under-Secretary Henry Scrymgeour-Wedderburn (West Renfrewshire) closed it.

The Problems

Focusing the mind of politicians, the industry and the newly established board, there were three major problems. The British annual herring catch had dramatically fallen from its pre-World War I high of 540,000 tons to just over 250,000 tons by the early 30s. Meanwhile, a collapse in exports meant that, even so, there were often unsold surpluses. To top things off, although the home market wasn’t on anything like the scale of exports, it too was decreasing.

Before the First World War, Russia and Germany had provided the great markets for British salt herring – the so-called Scotch Cure – taking 80% of exported production, which was most of the production. The beauties of salt herring almost entirely passed the English by, but it accounted for the bulk of the catch.

Between the wars, the Soviet Union and Germany were short on hard currency. The Soviets, in particular, played hardball on price, helped by the more competitive Norwegian and Icelandic herring fisheries, both of which were early adopters of purse seining. The Soviets and the Germans had also begun to increase their own herring fishing capacities.

Between jokey, constituent-facing claims as to where the best herrings come from, the positions in the 1937 debate are mostly gloomy, angry or defensive. Given the scale of the problem and the Board’s resources, the politicians were clearly expecting too much too soon, but the Board’s Annual Report gave little ground for optimism. It’s easy to imagine HIB representatives up in the gallery, head in hands.

Robert Boothby (Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern) offers a rare ray of hope in increasing exports to the USA and Palestine. These, however, mostly grew out of Poland’s encouraged Jewish emigration: schmaltz herring shifts rather than actual new markets.

Productivism

Despite general catch declines, herring could still be caught in abundance. Reduced salt herring production, however, also reduced temporary storage solutions for gluts and catches were sometimes thrown overboard. In the 20s and the 30s, with hunger an issue that had some political traction, the sense of this waste particularly exercised the Left in the debate.

Walter Elliot was a productivist: catch as many herrings as you can and create the markets to accommodate any resulting oversupply.

There are markets, though, and markets.

At MAFF, Elliot had been the man who introduced free school milk to address dairy industry gluts. He was urged, likewise, to distribute herring gluts to the poor, but he stood firm: You cannot feed necessitous children on raw salt herring. I can imagine nothing which would upset a child more. Not even hunger. And yet, there are plenty of cooked salt herring recipes. Tatties & (salt) Herring is a classic Scottish dish and was still widely eaten at the time – But maybe not in Glasgow Kelvingrove.

To be fair to Elliot, a free herring distribution schememight not have been the answer. The strange decline in Britain’s herring consumption has been linked aspirant social mobility and, very precisely, to the perception that it was food for the poor.

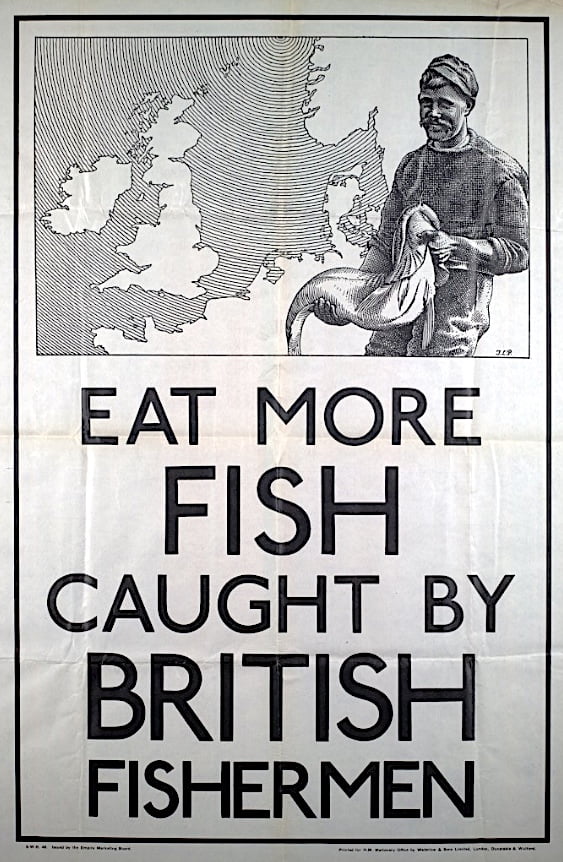

Elliot was a herring man, though. In the late 20s he’d worked with Financial Secretary to the Treasury AM Samuel – author of The Herring: Its Effect on the History of Britain (1918). Together, they had enabled the Empire Marketing Board’s support for the first documentary film, John Grierson’s Drifters (1929). Linked to the film’s release, before the EMB was wound up in 1933, it had mounted an advertising campaign, supporting British fishing, laying the ground for the HIB’s marketing work.

Eat more herrings!

In bringing the debate to its conclusion, Henry Scrymgeour-Wedderburn defended one strand of the Board’s work:

I do not know why herring are not more popular. I do not know enough about cooking, but I believe that cooking is one difficulty. They take a long time to cook, and also people do not think that they are good for children to eat because they have so many bones. If that is so, the best way of proceeding is to try to overcome that prejudice, and advertisement is one of the best ways of doing it.

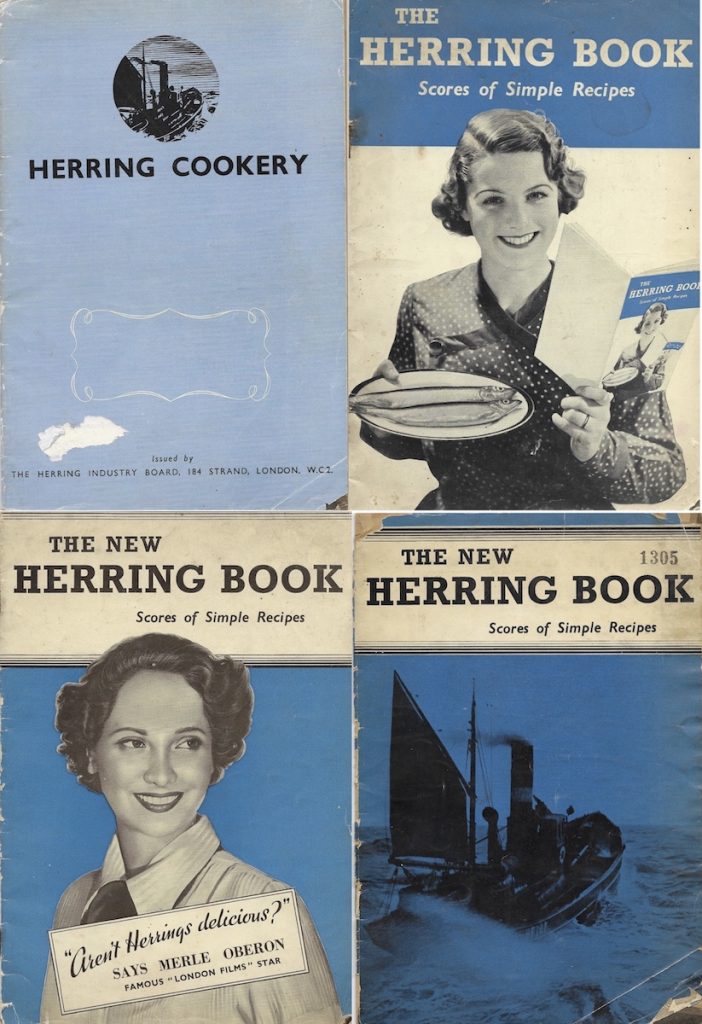

Between 1935 and 1938, the Herring Industry Board produced at least four versions of what was essentially the same booklet: Herring Cookery, The Herring Book and The New Herring Book (two editions). Strangely, the first is attributedto Mrs Arthur Webb, the well-known B.B.C. Cookery Expert, the second to another cookery writer of the time, Mrs Stanley Wrench. Both editions of The New Herring Book are back with Mrs Webb. The fourth was published as a Souvenir of the Herring Cookery Demonstrations Held at Great Yarmouth, August 15 – 19, 1938.

Sweating their assets, in the late 30s they also produced another booklet, In Search of Silver Treasure, using the cover photograph from the cooking demo souvenir, rehashing some of the material and dropping both cookery writers from the credits.

In March 1938 the Board made a bid to enlist educators working in schools, colleges and community contexts such as the Women’s Institute and the Workers’ Educational Association. Lecture Notes on the Herring speaks to an imagined proselytising army of harengophiles:

The subjoined lecture notes on the herring and the herring industry have been furnished in a partially connected form with a view to assisting those desirous of giving instruction on this subject to either juveniles or adults.

The wording has been rendered as simple as possible and it has been left to the discretion of the lecturer or instructor to make such alterations in phraseology or such additions in respect of local colour as may be deemed necessary to make the discourse suitable to the mentality of the audience addressed.

Meanwhile, the celebrated Parisian fish restaurateur Madame Simone Prunier opened a London branch in 1935 and it seems likely that the HIB was involved at least in encouraging her response to the difficulties of the East Anglian herring fishery. The Prunier Trophy, sculpted by Charles Robinson Sykes, who had designed the Rolls-Royce Spirit of Ecstasy, was awarded to the boat that made the largest single shot herring catch of the year. Winners also received £25 and an invitation Maison Prunier.

The first winner, in 1936, the Aberdeen steam drifter Boy Andrew (Skipper: J Mair) caught 231 crans of herring. The last, thirty years later, was the Fraserburgh motor drifter Tea Rose (Skipper: C Duthie) with only 128 crans.

Madame Prunier celebrated the award by getting her chef Maurice Cochois to create Filets de Harengs Trophy:

Fry fillets of herrings in clarified butter, and serve them in this way. Two fillets on each plate, roughly chopped tomatoes tossed in butter on top, then another fillet to make a sandwich. Cover with a light Sauce Thermidor, and brown lightly.

Interlude with bombs

The Herring Industry Board took a break from its work during the Second World War. Much of the fishing fleet was commandeered by the Royal Navy and directed towards mine clearance – coincidentally noticing the effectiveness of ASDIC and SONAR equipment in identifying shoals of fish.

Meanwhile, Walter Elliot, having returned to the back benches, was passing the Houses of Parliament on the night of September 26th, when they were being fire-bombed. It was he who told the firemen to concentrate on saving Westminster Hall and its medieval hammerbeam roof and not to bother about the House of Commons, which was only Victorian Gothic.

Overfishing

With hindsight it’s easy to see signs of overfishing between the wars. Drift net herring fishers had identified the danger back in the mid C19th, when they fought against the rise of ring netting on Scotland’s West Coast.

They had played a key role in encouraging the development of scientific fishery studies in the late C19th. They’d wanted impact assessments of the greater and indiscriminate catch capacity of trawl-based methods (which included ring netting). Thomas Huxley, the big boy of late C19th fishery science, had, however, decided that to all intents and purposes, herring populations (and other fishing stocks) represented a limitless supply.

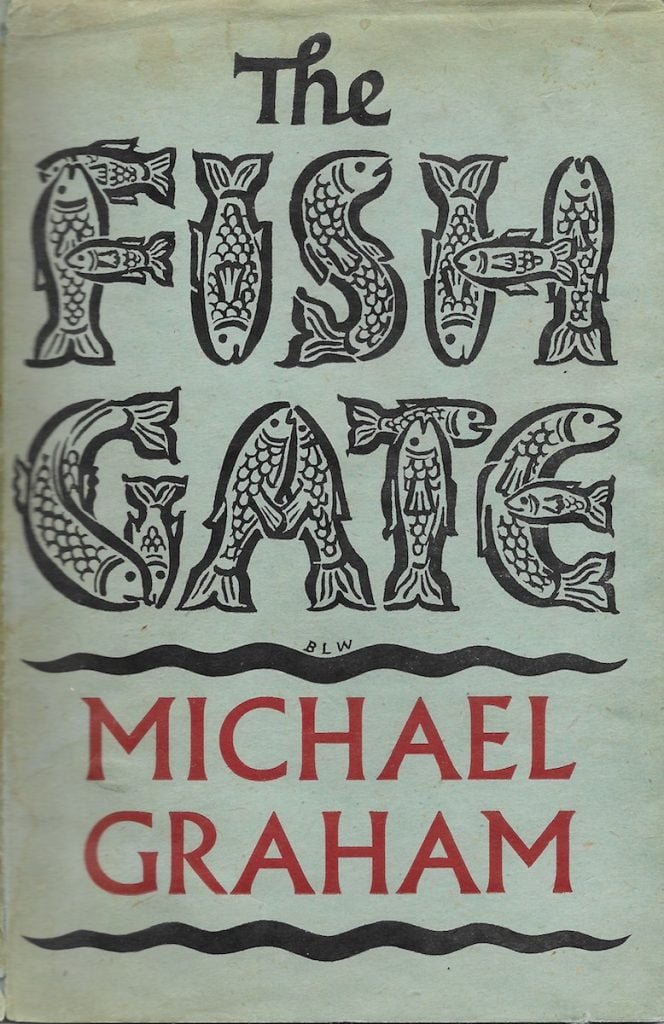

In 1943, the visionary fish scientist Michael Graham published The Fish Gate (named after one of the entrances to Jerusalem). At the heart of it is what he calls The Great Law of Fishing: Fisheries that are unlimited become unprofitable. He continues, Perhaps it is necessary to have a version for the socialist state of mind. If so, we might put it: Fisheries that are unlimited become inefficient, but I shall continue to use the word ‘profit’ here, having noted that in my argument it is only an index of efficiency.

A couple of pages earlier, he had written:

One of the strangest and most sardonic effects is on the position of the inventor. His invention is first hailed as just what is required, to remedy the fallen catch per ship with the old gear. The novelty produces excellent trips of fish at first. Those who use it say, ‘You must be up to date’. But soon everyone has it; and then, in a year or two, it reduces the stock to a new low level. The yield goes back to no more than before, perhaps less; but the fisherman must still use the new gear. He was better off without it; but, owing to the depleted stock, he could not manage without it now. He needs the additional fishing power that it gives, in order merely to stay where he was before it came in, so he has to accept the expense.

From 1945 to 1958, Graham was Director at the Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries’ Lowestoft laboratory – running what later became CEFAS (Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science). Some at the HIB, at least, will have read the book. In 1975, 17 years after Graham had retired, they included it in The Herring Story’s suggested further reading list.

The Fish Gate provides a yardstick by which to measure the Board’s work from the mid-40s onwards. By 1975, of course, North Sea herring populations were collapsing.

Modernising the British fleet

In a tragic opera of post-war UK herring fishing, the final act would come with those collapses. Initially led by Britain, in 1977 there was a European Community ban on herring fishing in the North Sea. The fishery on the West Coast of Scotland was closed the following year. In the Southern North Sea and on the West Coast, fisheries reopened in 1981, in the rest of the North Sea two years later. Populations have recovered variously, but the home market for herring never has, really.

It’s unusual to say this, but the British weren’t the prime culprits in the overfishing. Those honours go mainly to Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands, who, between the wars, had invested in diesel, pelagic trawl and purse seining. Britain had come late to the party.

In the late 30s, the Board had invested in decommissioning, made loans for new equipment and unsuccessfully set up a scheme to encourage new boat purchase. In the 1940s, however, the British North Sea herring fleet was still mainly made up of steam drifters.

By the early 60s, the once great East Anglian herring fleet had more-or-less gone. Blaming trawlers for its ills, there had been a reluctance to accept the full logics of modernisation. The Scottish industry, on the other hand, enjoyed a short-lived, minor boom on the back of HIB-supported investment in new boats and equipment.

The mesh of a drift net is designed to catch mature herrings, juveniles swimmming through. Mid-water or pelagic trawl nets and purse seine nets are dragged through the shoal. With echo location technology and large enough nets, they can surround it. Either way, the weight of fish caught blocks escape, juveniles included. As Michael Graham argued, without limits placed on the catch, the efficiency generates inefficiency.

The Icelandic herring fisheries had collapsed in the 1960s, so there’d been plenty of warning. Interviewed in 2005, the retired Scottish West Coast fisherman Jim Muir wryly notes the way the HIB enabled British fishermen to buy Iceland’s decommissioned purse seiners: The Icelandics have a good herring fishery yet. We don’t.

There is a remarkable passage in the Herring Industry Board’s Twenty-seventh Annual Report (1961):

The herring fishermen of this country are not directly affected by what happens to the Scandinavian herring stocks, only the fringe of which they touch by chance on rare occasions. They are well aware, however, that a great increase in the amount of trawling around Norway has been accompanied by a fall in the yield from the principal Norwegian herring-fishery just as catastrophic as that which has taken place in the North Sea.

Having regard to these misgivings, it may seem strange that, in 1961, the Board sponsored and supported financially experimental herring-trawling voyages by British craft and that they aim to repeat the exercise – on a larger scale – in 1962. The policy stems from two considerations. If trawling has no harmful effects on the stocks, it is proper to engage in it because of the possibilities which are claimed to be inherent in the method, of thereby reducing costs of catching and increasing profitability. If on the other hand, trawling for herring is harmful, we, in this country, are likely to be no worse off by joining others who fish in this manner and taking all we can get while the going’s good. Indeed, so doing and thereby threatening to bring so much nearer the time when there won’t be enough herring left to make fishing for them worth while, is likely to make all concerned far more eager than they now appear to be to agree upon and introduce measures of conservation. As Dr Samuel Johnson so cogently observed: “Depend upon it, Sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight’s time, it concentrates his mind wonderfully”.

If anybody happens to be in the market for a UK herring industry opera, this would be the basis for its big aria. Something in it speaks to Hamlet’s There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow soliloquy.

Reduction plants

British herring fishing had traditionally been focused on human consumption. To cope with their indiscriminate catches Norway, Denmark and Iceland had long since developed reduction plants for the production of herring oil and fishmeal.

Herring oil was used in manufacturing high explosives and had been key to the German war effort. With this in mind, in 1941, 570 British commandos had destroyed four Norwegian fish oil plants on the island of Måløy. Fishmeal is less exciting, mainly used agricultural feed (complaints of mass-produced Danish pork tasting of fish are not uncommon).

After the war, the HIB encouraged the development of the UK’s own fish processing plants, mostly in Scotland. The surplus herring was transported from port to plant by road and rail, but there were problems. After complaints about the smell, the board had to go to the unplanned expense of sealed steel containers. And then, after all the Board’s investment, in the late 50s Peru went and undercut European fishmeal.

The devastation of Peruvian anchoveta shoals led to a collapse in seabird populations and, consequently, guano production, but that’s another story. Well, all right, it’s the same story with different fish.

The Board did its best to keep going with its reduction plant strategy in the 1960s, but it became increasingly untenable.

The home market

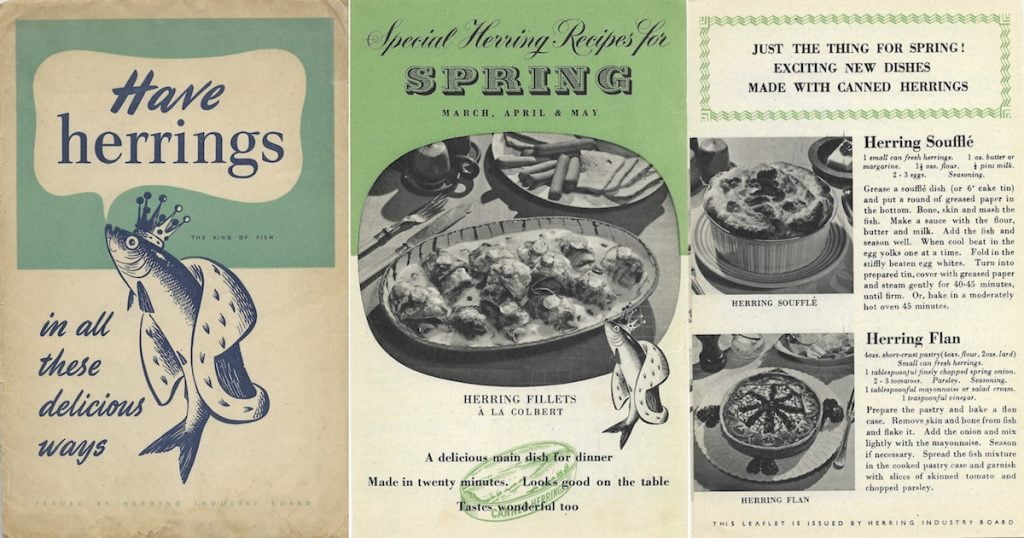

The 1961 Annual Report admits, herring and kippers are not, unfortunately, items which appear either regularly or, indeed frequently in every housewife’s shopping-list. There’s a feature in the Co-operative Wholesale Society’s Family Fare recipe book (1960), A Herring Dish for Every Month of the Year and eight of its recipes come from earlier HIB publications in my collection. Names are sometimes changed and CWS margarine, chutney and salad cream are substituted for some of the original ingredients, but the Board’s hand in encouraging change in the housewife’s shopping list is clear.

The 1961 Annual Report reveals experiments with packs of kippers suitable for dispensing from coin-operated machines. There’s a nice 50s/60s Sci Fi feel to the idea, but the Modern Age clearly wasn’t ready for Vend-O-Kippers.

Driven by a tragic sense of the herring simply not swimming with Britain’s changing times, the Board was always focused on its bones and the British housewife’s relentless search for increased convenience. Where the 1930s booklets had diagrams of how to fillet them, the monthly recipe leaflets of Have Herrings (1940s or 50s)all included features on canned herring dishes.

The board developed several experiments in fish freezing technology. In the early 50s at their Great Yarmouth plant, Birds Eye Frozen Foods developed prototypes of a herring fish finger, but by 1955 sampling groups of the British housewife had shown a clear preference for the alternative offering of cod.

Sometimes the gods themselves are against you.

The end

Around the same time as the Herring Industry Board was repackaging and updating its interesting educational facts in The Story of the Herring, it brought out a new edition of The Herring Book with colour spreads and entirely new recipes. I was sent a copy by a kind woman at Caledonian Oysters, but, in trying to get an exact date for it, I haven’t yet found another copy online.

Maybe distribution was paused with the 1977 moratorium on herring fishing. In 1981 the Herring Industry Board was merged with the White Fish Authority to for the Sea Fish Authority. With no one to fight its corner anymore, even though herring fishing started up again, fewer and fewer found their way to the fishmongers’ slabs of Great Britain.

Acknowledgements

In writing this entry on the Herring Industry Board, I have drawn on two articles by the excellent Chris Reid of Portsmouth University, From Boom to Bust: The Herring Industry in the Twentieth Century (2000, included in England’s Sea Fisheries: The Commercial Sea Fisheries of England and Wales since 1300, ed Starkey, Reid & Ashcroft, Chatham Publishing) and Underutilization, Undersupply, and Overfishing in the Herring Industry 1930 – 1980: A Case Study in the Evolution of Britain’s Productivist Fisheries Policy (2020, included in Too Valuable to be Lost: Overfishing in the North Atlantic, ed Garrido & Starkey, De Gruyter Oldenbourg).

I’d also like to thank Leila Burrell-Davis and Ros Castell for the Great Yarmouth Cookery Demonstrations 1938 Souvenir edition of The New Herring Book, @Oyster_Lady of Caledonian Oysters for her mother’s 1970s Herring Book and Nod Knowles for the Co-operative Wholesale Society’s Family Fayre (1960) with its A Herring Dish for Each Month of the Year promotion.

Parliamentary Herring Industry Debate, 1937

A big thanks to Hansard for this transcript of the herring industry debate. I’ve reformatted it and clarified some of the MPs names and constituencies. It’s always a joy to sample the quality of our masters’ deliberations…

Parliamentary herring industry debate, 22 July 1937

Motion made, and Question proposed, That a sum, not exceeding £35,000, be granted to His Majesty, to complete the sum necessary to defray the charge which will come in course of payment during the year ending on the 31st day of March, 1938, for Grants in Aid of the general administrative and other expenses of the Herring Industry Board and of the Herring Marketing Fund.” Note: £17,000 has been voted on account.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

I think it is of interest that this Debate, although it takes place on the Scottish Estimates day, is in fact a United Kingdom Debate. The Herring Industry Board is a United Kingdom body, and, as was pointed out when the scheme was going through the House, although the headquarters of the industry are in Scotland, the Board itself covers the United Kingdom, and, as its activities cover the United Kingdom, any of its functions can be raised today. That is specially necessary in connection with the herring industry, because, although we have two Ministries, the Scottish Fishery Board and the English Department of Fisheries, the herring fishing is, as we all know, one fishing, and its problems cannot be considered separately for Scotland and for England. Consequently, the Minister, that is, the joint Minister, as the spokesman of the Board, has to justify the Estimates laid before the House.

It appears that this will be the only occasion on which the great British industry of fishing can be discussed this Session. The herring and white fishing play an important part in the life of the nation. Last year the British Fisheries produced 1,000,000 tons of fish, valued at the ports of landing at £15,750,000. Of these herring were a small fraction. The weight was 278,000 tons and the value £2,405,000. The herring and white fishing industry are also closely bound up together and in discussing, as we shall do, the affairs of the herring industry we must not forget entirely that the white fishing industry is also going through a difficult time and is making very active efforts to reorganise itself, the result of which efforts will come before the House, I hope, next Session.

But the economic importance of the fisheries is even greater in Scotland than in England. It is specially so in the case of the herring industry. The Board, accordingly, shows a reasonable division between Scotsmen and Englishmen for a United Kingdom body – six Scotsmen and three Englishmen. The most remarkable thing about the report is that it has been signed unanimously. It is signed by the Chairman, Sir Thomas Whitson, of Edinburgh, Mr Adam Brown, of Fraserburgh, Mr Gordon Davidson, of Glasgow, Mr William Forman, of Peterhead, Mr Mitchell, a curer, and also by Mr Neil Mackay, who, though his activities are mostly in England, is interested in the large curing industry in Scotland also. It is all the more interesting since the report does not entirely flatter our Scottish pride, and we owe a great debt of gratitude to the Board and its members for the very frank way in which they have stated conclusions which are in many respects not flattering to those who come from North of the Tweed.

The great industry of the herring fishing is the following of the shoals down the coast. We are fortunately placed, in that the track of the great shoals runs parallel to our east coast and, consequently, the fishers continually have the shoals before them as they pass down from Lerwick past Peterhead, past the Northumberland ports, right down to Yarmouth and Lowestoft and in some cases right down into the English Channel. The herring is a perishable fish and it is that perishable quality that has led to the great and important industry of herring curing. It is also that perishable quality that has led to certain incidents in the industry which have, perhaps, attracted more attention than they deserve in comparison with the importance of the industry itself. I refer to the temporary gluts which take place from time to time and on which the House feels very keenly that, having been once caught, any portion of the catch should be surrendered. It appears to some Members to be a paradox, an anomaly and even a crime.

Let me explain how this glut arises. I have said that the essential feature of the herring industry is the track of the great shoals right down the east coast from the northern islands. It has another feature. As the shoals reach our coasts in the first instance, the fish are not of such good quality as they are later on, and the May and June herring are not of such good quality as those that are taken in the autumn catch. The early summer herring used to be caught in great numbers and were sold for the export trade. Our people, fastidious and well supplied with food, have always shown themselves very chary of anything in the way of cured herring taken from the earlier shoals.

Mr Robert Boothby, Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern

Is it not a fact that the July Scotch herring is the cream of the whole?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

I do not wish to go into detail. I am doing my best to keep to the 15 minutes to which Scottish Members desire that I should limit myself. I will not go into the particular quality of a particular catch taken off a particular constituency, but I think in general the summer herring are for the export trade and the difficulty has been that that portion of the trade has become more and more difficult in recent years. In the far distant ports, for instance Lerwick, and even ports relatively distant, such as Peterhead and Fraserburgh, which though very near important centres, such as Aberdeen, are at a greater distance from the more important centres of population in the South, these highly perishable fish are taken in great numbers. A glut arises and herring are rejected, not in the sense of being thrown away to preserve the price but simply because it is not physically possible to handle them and get them as fresh herring to any place where they can be eaten in time. In so far as the destruction of fish can be explained by merely physical reasons, that they could not be processed in time to be brought to a place where they could be eaten, I hope the Committee will accept that as a full explanation. What is resented is the case, if such cases exist, where fish fit for consumption, near a market, are destroyed wantonly, or merely for the purpose of keeping up the price.

In the summer the fishing from Peterhead, Fraserburgh and other ports, such as Lerwick and Stornoway, inevitably leads to a certain number of gluts. I hope I can convince the Committee, from the examination that I have been able to give to the question, that these gluts arise from physical causes and that it will never be possible entirely to avoid gluts of herring when a large catch is landed at a distant port. Later on, during the curing season, it is seldom that any dumping takes place. As far as I am advised, if it takes place it is due to the fact that the staff and the plant are physically incapable of dealing with the whole catch, or that the herring reach port in such poor condition that they are not worth curing. No organisation can ever be maintained at a point where it will deal with very rarely recurring peak conditions and, if you were to retain the overhead charges of an organisation which could deal with the whole catch when every boat has come home fully loaded, you would be maintaining an overhead which would be itself a heavy burden on the industry.

There are no doubt occasions upon which a dispute arises between the curers and the fishermen as to whether, when there is an exceptional catch, the curers can pay the price asked, for to deal with such a catch exceptionally expensive processing must be undertaken, and naturally at that point the curers want a reduction upon the price they have previously paid and the fishermen naturally object to that reduction. My information is that in such cases it is very seldom that a dispute arises, that in most cases the two get together, and by turning a blind eye to some regulation or other they come to an amicable arrangement. But I do not deny that there may be some cases in which an actual destruction of fish takes place under these conditions. They are, however, extremely rare. The whole of the dumping of fish, taken together, amounts to not 1 per cent of the catch in the year, and 99 per cent of the fish caught are, in fact, brought to shore and used as human food. That perhaps helps the Committee to put in better proportion an essential feature of fishing – the occasional dumping.

Mr David Kirkwood, Dumbarton District of Burghs

Is the statement authentic that 99 per cent of the catch is not destroyed and that only 1 per cent is lost by being put into the sea again?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

Yes, I took great care to work out the facts. I am giving the figures for the year 1936 and those are the exact facts for that year. It was a fairly average year as these things go. With a full sense of responsibility I say that the average consumption of these fish caught around our shores is 99 per cent of the fish caught; one fish out of 100 may be thrown away, but the remaining 99 are brought to shore and used for food.

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

That refers to herring?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

Yes, it refers to herring. The proportion of white fish is different, because white fish keep better. Let me give the House two figures. In 1913 the British catch was 588,000 tons and in 1936 278,000 tons. That is a measure of the enormous falling off in the take of this industry. I do not think that the falling off is due to a shortage of fish. The herring are there to be taken, but what I have already stated shows that what we are dealing with is not the fact that an odd fish, one out of 100, goes back to the sea, but the failure to take the 200,000 to 300,000 tons which could be taken if the industry was on the same scale as it was before the War. The difficulty, of course, arises very largely in the export market, and there again let us recall the difficulties of other sections of the fishing industry as well as those of the herring section. The herring is an export fish, the white fish industry is an import industry, and the interests of the two sections are divergent. At one moment our white fishermen come and say, “We wish you to cut down the German quota of fish landed in this country, for you are putting our people out of work;” and at the same moment the other fishermen say, “By hook or by crook you must succeed in getting our quota of fish into Germany extended, or we shall be out of work.” Those are the difficulties of the post-war world. But they are the difficulties with which the Herring Board has to grapple.

Let us remember these difficulties when we feel inclined, as some people or some Members of the Committee do, to raise our fists to high Heaven and call for the heads of nearly all those who sit on this side of the Committee.

[Interruption.]

If my Hon Friend the Member for East Aberdeen (Mr Boothby) were in Russia today, he would be foremost in campaigns against wreckers. The problem before the Herring Board was a very difficult one. It called not only for energy and wise administration on the Board’s part, but for the co-operation and sympathetic understanding of the industry. No doubt the two sides have honestly tried to carry out the trust imposed upon them. I cannot claim, and I do not think they claim, that every step they have taken has been the very best that could have been taken, but I would also say that the industry itself has from time to time not been blameless in its attitude towards the Board. It has been a little apt to consider the Board as a committee of archangels sent to lift it out of its troubles, and not as a number of very human men, most themselves engaged in the industry, bending their energies to deal with the extraordinarily difficult problem which I have detailed to the Committee.

One of the main complaints made by the industry is that sufficient energy has not been displayed in recapturing the export markets. Take two of the great export markets, Soviet Russia and Germany. The characteristic of the purchases of Soviet Russia is that they are made by very hard-fisted buyers. In Russia you have the whole of that industry united in one single control of an ironclad character, and it is one of the hardest bargainers in the international trade. The quantities sold to Russia vary very much – from 12,000 barrels in 1930 to 105,000 barrels in 1935 and down to 20,000 barrels in 1936. The two last years, 1935 and 1936, exemplify the character of the Russian purchases, in that the 105,000 barrels were sold on contracts and for these the price was only 27s or rather less; and in the case of the 20,000 barrels the Board refused or failed to negotiate a contract, and these herring were sold at the market price. When Soviet Russia had to pay the market price it paid 35s a barrel for herring which the previous year it had bought at 27s. That explains the uneasiness of the Herring Board in coming into close bargaining with these extremely acute business men.

It is easier to deal with the comparatively mild and unbusinesslike purchasers of Nazi Germany. They purchase herring in enormous quantities and they buy them at the market price. As against the Russian purchases of 20,000 barrels and 105,000 barrels and 70,000 barrels the German purchase has run pretty steadily to such figures as 406,000 barrels in 1932; 375,000 in 1933; 258,000 in 1934; 438,000 in 1935; and 417,000 in 1936. It is true to say that the Central European market is proving more easy to sell in than the Eastern market of European Russia; the middle of the Baltic is easier than the far end, because in addition to the German purchases there are the Polish purchases, which are very important. We sold to Poland in 1932, 238,000 barrels; 213,000 barrels in 1933; 246,000 barrels in 1934; 269,000 in 1935; and 309,000 barrels in 1936. It is impossible, of course, to leave out of account altogether the influence of trade agreements in these matters, and the trade agreements have helped, I think. But let us not deceive ourselves. There are signs of a strong effort being made by Germany to develop her own fishing and to catch her fish for herself. We have to watch these developments of fishing fleets in other countries.

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

Is it not the case, as stated in the Annual Report of the Fishery Board, on page 25, that all imports of fish to the German market are regulated by a committee just as the Russian market purchases are regulated, and that British exporters have the same difficulty with regard to price in Germany as in Russia?

Mr William Thorne, West Ham Plaistow

Are the German fishermen entitled to fish in the same waters as our people from Scotland and England?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

Yes, certainly; these are international waters and anyone can fish in them. They are outside the three-miles limit. The herring shoals are out of sight of land very often.

Mr Frederick Macquisten, Argyll

They are fishing in Loch Fyne sometimes.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

There are very few Germans who fish in Loch Fyne.

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

What about the reference that I have mentioned?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

Of course it is true that in both Russia and Germany the import trade is highly regulated, but I think that the figures I have given show that up to the present it has been possible to sell a very much larger number of herring to Germany, and, indeed, to Poland, than to Russia. The price has been much closer to the world price than the very closely negotiated price obtained for the relatively small number of herring which the Russian market was willing to take. If we can get an improvement of international conditions then no doubt a general improvement of this export trade can be expected. But the white fish industry and the herring industry are to some extent at loggerheads, and we must take both their difficulties into account when we call for the utmost efforts to be made to get our export trade going again and to get fish into these foreign markets. That does not leave out of account the question of the most efficient and the most economical production of the herring here at home.

Mr David Kirkwood, Dumbarton District of Burghs

Before the Right Hon Gentleman leaves the question of exports of herring, what about our trade with America? Is our export of herring to America increasing or decreasing?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

The Board has published a very interesting table showing figures which include America. The figures of the American trade have recently been declining. I think that that is partly due to a falling off in the catch. There were 24,000 barrels exported in 1935, but the figure had come down to 18,000 barrels in 1936. There was some difficulty with the catch; there was not the same amount of herring available last year, but leaving the catch on the market resulted in a much higher price being paid for the fish. I do not wish to go into details; they are given at great length on page 16 of the report of the Herring Industry Board.

Mr David Kirkwood, Dumbarton District of Burghs

The great majority of those interested will read the report of these proceedings during the weekend.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

I believe that the people engaged in this trade read anything that is connected with the prosperity of their industry very closely indeed.

Mr David Kirkwood, Dumbarton District of Burghs

There are hundreds of people who will never see this report.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

What I am now saying will be of value to them and will excuse the trespass which I am making upon the time of the Committee. On the question of the production or economic catching of herring, the report of the Herring Industry Board is really of very great value indeed. They have compared the results achieved by the Northern and the Southern half of this industry, and even the most vehement of us who come from the North must admit that it makes very strange reading. On page 9, after reviewing the catchings, they say: These figures show a difference in favour of the English vessels of 42 per cent in the amount of crans per landing and over 34 per cent in earnings per vessel. They go on to say: Even if full allowance is made for the greater knowledge of the English fishermen of their home grounds it seems that this difference must be attributed in the main to general inefficiency due to the effect of autumn weather upon vessels and gear which had become inefficient owing to long continued lack of repair and maintenance, but if these disabilities were removed and the vessels and gear put into good order there is no reason why the Scottish earnings from week-day fishings should not be on a scale comparable with those of the English. It is true that the facts seem to show that the English system is, for some reason or other, better fitted to existing conditions than the Scottish system, and I have been asked what the difference is. The general reason I have been given is that the English fishing is conducted by much larger units than the Scottish fishing. I do not mean in larger boats, but in larger aggregations of boats. It is done by companies, and these companies are able to give better service and also – and this is very important – to stand the loss which occasionally arises from accidents due to storm or to stress of weather. The companies are able to stand the expenditure upon an individual boat much better than an individual whose whole capital is invested in the undertaking. This is a further rather unpalatable fact. The English boats keep at sea longer than the Scottish boats. The Scotsman, with his whole capital invested in one boat, when a storm begins to rise and the sky becomes overcast, not only risks his life, but his gear, and, therefore, makes for home. The Englishman, with the very much greater resources of a company behind him, is willing to take the risk, and very often successfully takes the risk, and thereafter he is on the spot to begin fishing again, whereas his Scottish colleague has run for port and has to make his way out again to the fishing ground. He meets, on his way out to the fishing ground, his English competitor coming in fully loaded to meet a short market.

Sir James Henderson-Stewart, Fife Eastern

Is the Right Hon Gentleman satisfied that this is a fair general picture of the position between the two countries? It does not seem to me to be quite a fair representation of the Scottish fisherman’s job.

Mr George Garro-Jones, Aberdeen North

I do not wish to interrupt the Right Hon Gentleman’s very interesting survey, but is it not the fact that the value of this comparison is almost entirely set off by the fact that it does not take into account the comparative cost of running the two fleets, the English fleet being known to have larger overhead and other charges than the Scottish fleet.

Mr Frederick Macquisten, Argyll

Is not the fish caught by the Scottish fishermen much fresher than that caught by the English fishermen? Is not Loch Fyne-caught fish landed beautifully fresh; and it is not much better than fish sold in London?

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

Loch Fyne is nearer Glasgow than the Dogger Bank is to London. You cannot get away from that fact. The Lower Clyde is very near to a great centre of population, but I do not wish to go into that point. Fish is certainly fresher if a man has been on the Bank all night and has risked the weather and then comes in with a cargo of fish, than is the case of fish caught by someone who has been hanging about. The Hon Member for East Fife (Mr Henderson-Stewart) asked if that is a fair picture. It is just that danger which makes me unwilling to dogmatise. I think we should be rash in coming forthwith to a conclusion on this matter. I am only telling the House what has been told me. Moreover, a private individual who gives up his trade and independence to a large company will have the greatest difficulty in ever recovering it again. We must be sure, before we urge people into a collective system, that they will get benefit from it.

I would say in reply to the Hon Member for North Aberdeen (Mr Garro Jones) that I do not think it can entirely be said that the extra takings of English vessels are offset by the extra costs. The board have a paragraph on the point. In paragraph 45 they say: When statements on the above lines have appeared in the Press they have been met by the criticism that a comparison of gross earnings leads to fallacious conclusions and by the suggestion that the English owners of vessels and nets and the English crews are no better off in the long run for their longer and more intensive fishing because their extra earnings are all absorbed by – I think that that was the Hon Member’s point – additional expenses. They give figures to show that that is not entirely borne out, at least by arithmetic, since they show that: the English owner has more than two-and-a-half times as much money available to meet the costs of maintenance and repair of his vessel and nets, depreciation and overhead charges as had his Scottish competitor. I do not think that this discussion is yet settled, but in drawing attention to these comparative figures, the Board have performed a valuable service to the industry, and more particularly to those of us who are interested in the Scottish industry. Here is a point to which this House, the industry and the Herring Industry Board will need to devote attention. It is no use saying that we should get out of our difficulties by some grant, or subsidy or other. The difficulty lies far deeper. It has been suggested in a memorial put forward that a subsidy should be granted to the herring industry. That is a very curious remedy, and the Right Hon Gentleman the Member for West Stirling (Mr Johnston), who has so often, and quite rightly, inveighed against selling milk to Czechoslovakia at a price lower than that at which we can get it over here, would also comment on the fact if, by reason of a subsidy, we were selling to Continental nations, either to Russia or to Germany, herring at prices below those at which the poorer people in this country could get them.

Mr Robert Boothby, Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern

There is this difference. The Germans and the Russians like raw salt herring and our people will not eat them.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

I would not like to be given the task of justifying to an unemployed man in Bridgeton the selling of herring to Russia at half the price at which I was willing to sell it to him. It has often been suggested that in some way or other we should deal with the question of gluts by picking out the poorer classes of the community and making the herring available to them at cheaper prices. But we might run into very considerable difficulty. That seems to be getting pretty close to the old theory of relief in kind. We have to sell herring to people because they like herring, and not because we have got a lot of herring and want to get rid of it. There is nothing that the unemployed would resent more than feeling that they were the dumping ground for some surplus food product.

Mr William Gallacher, Fife Western

You try it.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

I can imagine the Hon Member for West Fife (Mr Gallacher) making a very effective speech on the subject.

Mr William Thorne, West Ham Plaistow

That does not apply to feeding necessitous children.

Mr Walter Elliot, Glasgow Kelvingrove

You cannot feed necessitous children on raw salt herring. I can imagine nothing which would upset a child more.

We must make every effort to develop the export market, but also I do not take the view of the memorialists, that the home market is saturated and cannot absorb more herring. I think there is every reason to think that it can absorb more herring. We are more likely to find an outlet there than before especially now that times are more prosperous and there is more employment about and more purchasing power in the hands of the people. The northern half of the industry is taking less fish and less money than the southern half, and the northern half is less highly organised than the southern half. Would the northern half be willing to work under the mere highly organised conditions of the south and take more fish and more money? The Board do not come to a conclusion on that point and I am disinclined to come to a conclusion on that point myself. I shall consider very carefully the further investigations of the Board, and I shall especially value the opinions of Hon and Right Hon Members of this House.

The fact is that the industry is undoubtedly still in a very serious position. At the same time, the position is not without hope. The value of herring landed in Great Britain went up from £1,519,000 in 1934, to £1,960,000 in 1935, and to £2,406,000 in 1936. Between 1934 and 1936 the increase was over £800,000, or 33 per cent It is the same for the earnings of the average drifter, even for the Scottish drifter. In 1934 the average earnings were £915, and in 1936 they were £1,685. It, therefore, seems that the position, though difficult, has hopeful features in it, and it is clear that there is a living in the herring industry for many thousands of our own people. It is to the improvement of their position and to the extension of the industry that the Committee, Parliament and the Herring Board must bend all their efforts in the immediate future.

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

I beg to move, to reduce the Vote by £100.

I move the reduction with a view to calling attention to the perilous plight of the herring industry in Scotland and the extraordinary document which has been issued by the Herring Industry Board. I have never read a more depressing White Paper. It goes to the length of discussing whether our great herring industry may some day be lost to us. It is a document the writers of which spend most of their time in trying to prove that nothing can be done for the industry. Every proposal that is put to them for aiding the industry in the difficult times through which it is passing is politely pushed aside for one reason or another. That attitude the Right Hon Gentleman has endorsed this afternoon, with the exception of his closing sentences.

What is the position in which we find ourselves? I spent some time yesterday in the Library looking through the census figures, and I noticed that in the county of Aberdeen the fishing population has fallen by one-third in the last 10 years. I looked at the report of the Ministry of Fisheries for June of this year and I saw that 70 trawlers were laid up in Aberdeen Harbour. We have it officially stated that the Buckie herring fleet is only now at one-half its pre-War strength and that it is disappearing at such a rate that in five years it will have disappeared altogether. One drifter goes every 10 days. Steam drifters are disappearing at the rate of 12 per cent per annum, and the value of the fishing fleet is falling by £68,000 per annum. What is the remedy? What are we told this afternoon? There are 58,000 workers employed in the industry either at sea or on shore. I am not sure whether that figure includes the workers employed in curing, but leaving aside the question of whether or not the curers are included, it is a fact that the men, women and children depending upon the industry number somewhere about 250,000 persons. Yet the Herring Fishery Board in regard to herring, which are our greatest catch, have nothing positive to offer, nothing immediate, nothing really hopeful to put before us.

I want to devote myself this afternoon to constructive rather than destructive criticism. I have no reason to contradict what the Right Hon Gentleman said about the personnel of the Herring Board. I know nothing about them personally. The Hon Member for East Aberdeen (Mr Boothby) has views on the personality of the Board and perhaps he will state them. It is not with the individuals that I am concerned. I want to see whether it is possible within what we call the capitalist method of production and distribution to find a better living for the people who are now engaged in this industry. If it is not possible to continue as we are doing, with competing sections operating for profit and all failing in the process, is it possible to suggest alternative methods?

I have been at some pains to go into this matter. There are two markets for our herring, the home market and the foreign market. The home market is, roughly, one-third of the total. Obviously, the remedy that must be applied or sought for must be different. In regard to the home market the Right Hon Gentleman has dismissed, with some rather injudicious phrases, the idea that we should supply any herring surplus to the normal quantities that the markets can take, cheaply to the needy and the poor who cannot purchase at present prices. He said it would be an insult to the poor – I did not take down his words exactly – to ask them to consume this food at lower prices. I dispute that entirely. It is no insult to the poor to consume cheaper milk either in schools or elsewhere. It is no insult to the poor to get reductions in house rents.

It is a vital necessity both to consumers and producers that there should be as few barriers as possible between the worker who produces good food and the empty stomachs in our industrial areas. I have heard all sorts of fancy objections put up against a scheme of that kind. I am told that we cannot maintain a permanent system of distribution to deal with occasional surpluses or exceptional gluts. That is true, and nobody has ever proposed anything of the sort. Last Friday I met a number of directors of the Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society, with their fishery buyers, and I have had a letter from them this morning confirming what was said to me last Friday. Here is the greatest trading organisation in Scotland – whether one likes co-operative societies or private traders does not matter – with agencies in every industrial town, and every industrial village in Scotland and the co-operative wholesale society directors – I can give the Right Hon Gentleman the secretary’s letter to me – declare that they are willing to place their great organisation at the disposal of the Secretary of State, to ask for no profit at all, in order to deal with this question of occasional surplus and to see to it that these surpluses reach the stomachs of the poor in the depressed areas at the minimum possible price. That is not an offer that can be derided. It is not an offer that the Secretary of State can turn aside with a joke about poor people, babies and toddlers eating salt herring.

Here are masses of our people not getting enough to eat, here is probably the most nutritious fish in the market, as the herring certainly is when it is fresh, and here are the hungry and distressed fishing population. It is our duty to organise production and distribution in such a way that production shall not be for profit but for use, and we have the Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society saying that they are willing to work a scheme without profit. I suggest to the Secretary of State that without further ado he should get one or two of the very able young civil servants on his staff, than whom there are none abler in Whitehall – they are not a band of no-men such as they collect at the Treasury; they are men with open and agile minds, willing to break new ground – and send them to negotiate with the Scottish Cooperative Wholesale Society and see what is in the proposal.

Mr Pierse Loftus, Lowestoft

Is the proposal to distribute fresh herring during periods of glut or to salt and distribute them?

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

I am talking about fresh herring during periods of glut. I said that the herring when it is fresh is the most nutritious fish. The Secretary of State said that only 1 per cent of our herring catch was thrown back into the sea in 1936. That may be true, but it does not face up to the fact that you are deliberately restricting your market. That is the policy of the Herring Industry Board. You are buying up trawlers and vessels and destroying vessels. You are limiting the output in every possible way, and when the Right Hon Gentleman says that only 1 per cent of the fish caught are destroyed that does not meet the whole difficulty. The point is that the fishing population is steadily on the decline and that you are throwing more and more upon the Poor Law and public assistance at a time when the people ought to eat more fish.

I should like briefly to refer to the export market. I want to keep strictly to my time limit in order to set a good example to other Hon Members. The Right Hon Gentleman told us something about the Russian and German purchases. Here, again, he ought to send his ablest civil servants. I do beg of him not to accept these cast-iron, individualistic, nonsensical stories that are being handed out. I have been to the Russian buying organisation in London this week. I had a discussion with the officials, and I have the figures. I have the inside story of prices. I know what they are paying for their herring and I know what they are willing to negotiate upon. We sold to Russia last year 4,450 tons of fish. I cannot translate it into crans and barrels. They bought 10,330 tons from Holland and 6,280 tons from Norway. For the 6,280 tons from Norway they paid about 650,000 roubles less than they had to pay for our 4,450 tons. There is something to be looked into here, something to be examined. I have seen their papers and I am prepared to stand by these figures. You cannot develop a trade on those lines.

What are the Russians prepared to do? If the Right Hon Gentleman can organise something in the nature of a co-operative organisation among the fishermen and curers in Scotland, the Russians are willing to deal with them on this basis, that they will take at the normal market price whatever it is, a bigger proportion of the catch at that price than they bought last year. The Right Hon Gentleman hardly did justice to the Russian market. It is true that they bought 20,000 barrels last year, but there have been years when they have bought 700,000 barrels, and 750,000 barrels.

Mr Frederick Macquisten, Argyll

How long ago?

Mr Thomas Johnston, Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

I think that was in 1911. This is a great market, an almost unlimited market. They are willing to take salted fish, the peasants like it, and they are willing to pay for it. In 1931 I was set the task in the Labour Government of trying to get trade going quickly, and I induced the Russian Government to give us £6,000,000 of orders for the engineering firms in this country, and I got credits extended to Russian trade. They are willing to take more barrels of any alleged surplus at a lower rate, which can be agreed upon. We have sold herring to Russia at 22s 6d a barrel, the price last year was 26s. It is always fluctuating. Why not give a firm deal to these people. They are not fools. If they can buy herring cheaper in Norway and Holland they will do so; but they are friendly disposed to us. Credits have been extended; and all the credits granted by the Government have not been eaten up. I hope the Right Hon Gentleman will send one or two of his staff to discuss the matter with Mr Bogomoloff, Mr Pickman and Dr Segal of the Russian delegation, and the appalling state of affairs on our Scottish coasts can be tackled. It can only be tackled by co-operation at both ends. Individualism must go. Waste within the industry must disappear. If the Government will examine the problem on these lines then the expectation printed in a Government document that the day may come when we shall see the last of our herring industry, need no longer be printed in a Government publication.

Sir Archibald Sinclair, Caithness and Sutherland

I join with the Right Hon Member for West Stirling (Mr Johnston) in protesting against the pessimism in regard to the future which marks the report of the Herring Board, and also in emphasising the present depression in the industry. There is the formidable paragraph on page 6 of the report where they point out that: When the proper deductions from the total revenue realised by the catchers are made for the value of herrings caught by trawlers, ring-netters and inshore fishermen the amount remaining is not sufficient for the maintenance of the main drifting fleet and their crews. It is from that that all the ills of the herring fishery flow. The unemployment figures in these ports are tremendous. In Wick it is 28 per cent, Peterhead 21 per cent, Buckie 20 per cent, Lerwick 20 per cent and Stornoway 43·8 per cent These percentages were for the period when the herring fishing season was getting into its stride – the end of June. A few months before they were much worse. At the beginning of July there was a total collapse of the industry in some places, and in Wick, one of the principal fishing ports in Scotland, there was one day when only three arrivals of herring fishing boats took place. What are the causes? The report points out a number of them. There is first the lack of resilience in the home market. I have always doubted whether the home market would fulfil the expectations which many Hon Members have expressed, and actually, in spite of all the efforts made by the Board, the consumption at home declined last year from 491,000 cran to 473,000 cran. Nevertheless, the Board point out that you cannot judge by one year’s efforts, and it is reasonable to suppose that these efforts will show greater fruits in later years. They mean to continue them, and I wish them luck, but at the same time I hope they will consider new ideas such as that of working with the Co-operative Wholesale Society as suggested for by the Right Hon Member for West Stirling. It was impossible for the Right Hon Gentleman in a speech of a quarter of an hour to develop the ideas he has, but I hope the Secretary of State will go carefully into the prospect of developing the home market on the lines suggested by him.

I was not convinced by what the Secretary of State said that the poor would regard it as an insult to have herring at a cheap price. We have a milk scheme to give people, who cannot afford to pay the ordinary prices of milk, cheap milk, and a potato scheme was tried in one depressed area. Why cannot we have a herring scheme? I do not suggest that the Government should rush into a great scheme embracing the whole country next week, but, at any rate, let us have an experimental scheme and it may be that something may come out of the proposal put forward by the Right Hon Gentleman. Why cannot we have an experimental scheme on these lines in some great centre of population for the sale of herring at cheap prices to the unemployed, and to those who cannot afford to buy them at the ordinary market price? At any rate, I am sure that it is only on lines such as these that you will be able to develop the home market. I doubt very much whether it is capable of much development on normal lines. But far more important is the need for developing the foreign market. The Board point out in paragraph 83 that: It is impossible to increase trade with certain countries because of the existence of import duties which when added to the cost of production, processing and transport make the price almost prohibitive to the local population. That, of course, is another illustration of the fact that the tariff as a bargaining weapon has completely failed to make room for our exports in foreign countries. The Board also point out the need for lower catching and curing costs. That is a fundamental question, whether you are going to sell in the home market or in the foreign market. High prices, the Board point out in paragraphs scattered all over their report, have proved an obstacle to them in developing the home and foreign markets. The Secretary of State referred to the development of fishing fleets by Germany. That, of course, is part of their policy of autarchy upon which they have embarked. Dr Schacht declares that they have done so unwillingly and that they would much prefer to enter into a policy for the general lowering of trade barriers and a revival of overseas trade. In short, the main lesson to be drawn from the Herring Board’s report is that no industry stands to gain more – both by a reduction of its costs and by entry into foreign markets – from a policy of economic disarmament and freer trade than the herring fishing industry, and I wish I could believe that there was any prospect of the Government throwing itself into this policy, to which they constantly pay lip-service, with that energy and resolution and even that measure of ruthlessness which it requires for success.

Of course, of the foreign markets, Russia is the most important. The Right Hon Gentleman referred to the fact that the Russians were able to buy Dutch and Norwegian herring cheaper than Scottish herring. So can anybody else. They are not so valuable an article. Their price on the world market is lower than the price of Scottish herring. I agree with the Right Hon Gentleman that we should reorganise our fishing industry and assist in the development of its marketing organisation, but if he means that we are to recast our system in order to meet the views and convenience of the Russians I do not see why we should do that. It is only if he means that we should impart into our marketing arrangements the maximum degree of efficiency and deal with the Russians on level terms that I entirely agree.

As a matter of fact, one of the difficulties of dealing with Russia has been that they drive too hard a bargain. It has more than once happened that when the Board has tried to make a bargain at a certain price the Russians have refused it and afterwards they have come back and bought herring at the very price at which they were first offered them by the Board some months earlier. I agree with the Right Hon Gentleman in saying that we must put our own house in order, make ourselves as efficient as we can, but I would also say to the trading representatives of Russia to whose courtesy I should like to pay a tribute, or perhaps to say to their masters, that really in these troublous times in which we are living, when it is of vital importance that there should be friendship between the great Russian people and the people of these islands in the defence of great interests which we hold in common, it would be good policy if they would abandon their efforts to cut down the price of herring to the last shilling, and show their willingness to co-operate with us in restoring this industry which means so much to us in Scotland and to our people generally. They would be doing a good stroke of policy for Russia and for a better understanding between the two peoples.

In their report the Herring Board also draw attention to another problem, and that is the recruitment of women workers. It is getting more difficult to get women workers into the industry. Much has been done to improve the conditions of their work and I hope more will be done in the future. One of the difficulties is the difficulty about the unemployment insurance regulations. The women workers feel that the regulations are not fair. I do not intend to speak further on that matter, because it is not really a matter for which the Secretary of State is responsible; but as it greatly affects the interests of the fishing industry, for whose welfare the Right Hon Gentleman is so largely responsible, I ask him to consult his colleague the Minister of Labour on that point, which is brought to our attention in the report of the Board.

Time does not permit me to follow the Secretary of State in detail into his analysis of the Board’s statement about the comparative earnings of Scottish and English boats, but there are one or two remarks I would like to make on that, and I will do as the Right Hon Gentleman so prudently did, and refrain from dogmatism. The Board’s comments, and the comments made in certain letters and articles which appeared in the Daily Mail newspaper two or three weeks ago, seem to me to be unfair to the Scottish drifters and to show too little regard for the peculiarity of their circumstances. Scottish fishermen hold firmly to the system of individual and family ownership of their boats, or ownership by partners belonging to the local community. They would regard the prospects of company ownership with repugnance, for reasons connected with circumstances and traditions with which I fully sympathise. I would add that I do not believe that these English boats, which are supposed to be so successful, are all run by big companies.

Mr Pierse Loftus , Lowestoft

Hear, hear.

Sir Archibald Sinclair, Caithness and Sutherland

The Hon Member for Lowestoft (Mr Loftus) supports me. Many of them are owned by families and by quite small partnerships. It would be interesting to know whether the big companies in England are any more successful than these small partnerships. Moreover, in paragraph 38 it is pointed out that when the Scottish fishing boats meet the English boats on level terms, they get as good earnings as the English do; there is a difference of only £100 less for the Scottish – and their season was shorter. Another point to be remembered about the English boats is that their debts are much higher than the debts of Scottish boats. The English communities are much more deeply in debt. Therefore, we ought to approach the subject with care, and I was delighted that the Secretary of State refused to dogmatise about it and that he is keeping an open mind; but I would certainly lay it down that an alteration in the Scottish system of boat ownership ought not to be a condition of help from the State in the re-organisation of the fishing fleet.

What of future policy? First of all, it is vitally necessary to have new boats. As the Right Hon Gentleman the Member for West Stirling pointed out, the boats are now rapidly going out of use. There must be help in renewing the fleet. Moreover, the continual contraction of the fishing fleet is very dangerous from the standpoint of National Defence, a subject on which I have spoken before and which I will not elaborate now. Nevertheless I suggest to the Secretary of State that he might tell us whether there is any prospect of a retaining fee being paid to the owners of drifters who are prepared to hold them at the service of the State in the event of war. The mere re-conditioning of old drifters will not help. New boats are necessary. They cost about £6,000 each, and substantial help is required.

Secondly, a new sort of drifter is required. I have argued that for some years past, and I am glad to see that at last the Board are taking steps on these lines. Motor power will increasingly take the place of steam power, unless this new kind of steam drifter can be evolved. I hope that money will be available for experiments, and that a certain amount of priority will be given to them, even in these difficult times when so much of the Government’s resources is being devoted to Defence expenditure. Thirdly, I venture to say that too many restrictions are being issued by the Herring Board. Pages of this report are devoted to a list of all the restrictions which have been put on the work of the industry. We need to increase production and thus ease the burden of overhead charges. I hope that some such scheme as working with the Co-operative Society, if it will indeed help to get rid of surpluses and expand the home market, will assist towards that end.

In conclusion, I notice that the Board is to visit Scottish parts. I am sorry that Wick does not appear to be included in the itinerary, but I hope that that omission will yet be repaired. In my opinion, the Board ought not to return from Scotland, but ought to stay there, for that is its right place. One of the worst things in the report is to be found on page 2 where the address of the Board is given – 184, Strand, London. The Board ought to be in Edinburgh, for this herring fishing industry is much more a Scottish interest than it is an English interest. The powers of the Board should be extended, for it can do little at the present time except restrict. In England, with all its great industries – in London, the hub of the world’s commerce – the herring fishing industry may well seem insignificant and almost a superfluity, but it is indispensable to the economic life of Scotland. Let the Board throw off its pessimism and have faith in the future of the industry, and resolution to promote its revival.

Sir Arthur Harbord, Great Yarmouth

Hon Members are aware of the serious plight of the great herring industry. As is pointed out by the Board, that industry was placed in difficulties after the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, but those difficulties were overcome largely because of a greater demand from the Continent. Of recent years, however, a lesser demand has adversely affected the industry. The Right Hon Gentleman the Member for West Stirling (Mr T Johnston) said that Russia would be our good friend in the matter of buying herring, but my experience has been that the Russians try to cut down to the lowest possible figure the price they pay for our herring, which are of superior quality to the Norwegian herring. Incidentally, it must be remembered that the Norwegian fishermen catch the herring in the Fjords, which are quite near, and that they catch them in great volume, so that their catching costs are not as heavy as those which face our fishermen in the North Sea and elsewhere.

I ask the Government to give extended powers to the Board. I do not complain of the Board, for I believe that its chairman and members, faced with a difficult task, have conscientiously tried to better the conditions of all classes who are engaged in the herring industry. In my opinion, the Scottish boats are not kept in such good state as English boats; the English boats are better preserved than the Scottish boats. While I do not say that a complete reconditioning scheme could be adopted in the case of the fishing boats, there are certain classes of boats which have been well kept and well maintained and which, by wise expenditure, could be fitted to continue fishing.

I feel that the Government are unmindful of their obligations to the fishing industry. They have been most generous to the agricultural industry, giving it subsidies on meat, beet, wheat and beef, and excusal in the matter of rates, but when the suggestion is made that some subsidy should be given to the fishing community for purchasing new boats or reconditioning existing boats, every obstacle is placed in the way. During the Great War the fishing industry did great service to the country by minesweeping and mine-laying in all kinds of seas, in all conditions of rough weather, and with great loss of life. The work which those brave fellows did placed the Government under a great obligation to them. They helped to prevent the country from being starved into submission to its enemies. We need these fishermen as an auxiliary of our Navy.

The Right Hon Gentleman the Member for Caithness and Sutherland (Sir A. Sinclair) suggested that Germany would welcome arrangements which would promote freer trade, but I am doubtful whether that is so. By increased taxation of our imports they made it more difficult. Why are the Germans building their fishing fleet with such rapidity? It is because it will be an auxiliary of their navy and increase their armed strength. Russia is also building a fishing fleet. The difficulties which face our fishing industry are greater and harder than any which it has ever experienced before. The Government have not risen to the occasion. They have not sufficient faith in their own child, the Herring Industry Board. I urge them to give extended powers to that Board. The Government have such facilities of borrowing money at their disposal that they could scrap all the obsolete vessels at once and replace them by a smaller type of Diesel vessel, which as has been proved by recent experience, is more likely to be profitable and useful to the community. Such boats could be worked much more economically, thus puting the industry in a better condition to meet its competitors in foreign markets.

That help is due to that brave class of men whose bravery, heroism and sacrifice in the service of their country during the Great War earned such praise from Earl Beatty and Viscount Jellicoe. I am one of those who have not lost faith in the home market. I think it could be better exploited, and that there could be a greater consumption of British herring in this country. I do not think a sufficiently long time has passed for us to be able to judge the value of the publicity campaign. I believe that that campaign will have good results, and will lead to a greater consumption of herring by our people. I do not know whether the question of selling herring to Canada has been given sufficient attention. I should have thought that by the establishment of agencies there and by the use of various types of refrigerating craft it would be possible to send herring to Canada at a time when they would be very acceptable there. It is on those lines that assistance can be given to the industry. I thank the Fishing Industry Board for what they have done. I think they ought to receive encouragement rather than blame and that they ought to be backed up with greater financial assistance.

Mr Robert Boothby , Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern

I sometimes wonder to myself whether a rigid time-limit in these Debates is a good thing. This is the first occasion on which the herring fishing industry, which is vital to my constituency, has been discussed for a long time; and probably it will be the last for a long time to come. I could not help being impressed by the effect of the time limit on the speech of the Right Hon Gentleman the Member for Caithness and Sutherland (Sir A. Sinclair). All the way through, it seemed to me, he was on the brink of making an interesting speech; but just when he was coming to the point he would look at the clock and say, “I have not time to develop that point now.”

Mr David Kirkwood , Dumbarton District of Burghs

Does the Hon Member mean to say that the Right Hon Gentleman did not make an interesting speech?

Mr Robert Boothby, Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern

At all events I am going to make an interesting speech. It took me 18 minutes to make it in my bedroom this morning, and it will probably take me 22 minutes here; but I ask the indulgence of the Committee, because of the importance of this subject to my constituents.

Mr Thomas Johnston , Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire Western

Will the Hon Member permit me to say that while he and every other Hon Member of the Committee has of course the right to speak, it should be recognised that the only possible way of allowing all those who wish to take part in the Debate to do so, is by agreement among Hon Members themselves? I would beg the Hon Member, who will have other opportunities of raising this matter, not to upset the arrangement.

Mr Robert Boothby, Aberdeenshire and Kincardineshire Eastern