The sardine in cans, on the slab and in popular culture; the limits of self-identification for herrings and non-European pilchards

SARDINES

The difference which stands between

The Cornish pilchard and sardine,

Whilst taxonomically nil,

Is geopolitically still

A matter of which sardine you mean...

To understand the vexed question of sardine identity, we must go back to ancient Greece and Rome.

Paul Neucrantz of Lübeck (De Harengo, 1654) exhaustively establishes that the herring was unknown to classical authority. There is zooarchaeological evidence that Romans ate it in Belgium, but they didn’t tell Pliny. The Greeks and the Romans, however, were familiar with the sardine. The word derives from Greek, while the Romans called it Clupea. In contemporary Greek it is sardélla. The French call it sardine; the Spanish and the Italians sardina; the Portuguese sardinha; the English pilchard.

Linnaeus, father of taxonomy, was Swedish. Coming up with a taxonomical name for the genus of fish which included Atlantic herrings, he hit upon Clupea. And so, in 1758, the Atlantic herring became Clupea harengus. When natural historians considered the pilchard or sardine, it was natural that they should adopt Clupea pilchardus. And many did. In 1792, however, Johann Julius Walbaum of Lübeck, possibly aware of Neucrantz’ deliberations on the distinctly different and classically recognised sardine, came up with Sardina pilchardus.

Why does the sardine matter to an Encyclopaedia of the Herring? Well, apart from the similarity between sardines and herrings, on the eastern seaboard of North America, sardines are Atlantic herrings.

Digression upon Carousel and Juicy by The Notorious B.I.G.

In When the Children are Asleep from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s 1945, Maine-set musical Carousel, the herring fisherman Enoch Snow sings to his gal Carrie:

If I told you my plans and the things I intend,

It’d make ev’ry curl on your head stand on end…

When I make enough money outta one little boat

I’ll put all my money in another little boat.

I’ll make twiced as much outta two little boats

An’ the fust thing you know, I’ll have four little boats,

Then eight little boats, then a fleet of little boats

Then a great big fleet of great big boats –

All catchin’ herring, bringin’ it to shore,

Sailin’ out again an’ bringin’ in more,

An’ more, an’ more, an’ more!

The practically minded Carrie, aware, perhaps, that herring is not as popular as it should be, asks, Who’s gonna eat all that herring? And before resuming his song Enoch explains:

They ain’t gonna be herring. I’m gonna put ’em in cans a an’ call ’em sardines. Aha. Gonna build a little sardine cannery, then a big one, then the biggest one in the whole country. Oh, Carrie, I’m gonna get rich on sardines. Ah! I mean, we’re gonna get rich. You an’ me an’ all of us…

Fish conservationists today might want to interrogate Enoch’s plan, but he was probably still working on the basis of marine biologist Thomas Huxley’s 1880s inaccurate conclusion that herring, to all intents and purposes, was a limitless resource. Limitlessness in a resource-based capitalist model would, of course, have been a good thing, but the resulting low prices are not always associationally advantageous in the context of aspirational capitalism.

In Juicy (1994) when The Notorious B.I.G. or Biggie Smalls discussed his own individual economic and social progress (’cause I rhyme tight) he looked back on earlier days in the ‘hood:

Born sinner, the opposite of a winner;

Remember when I used to eat sardines for dinner.

The implication is that, whilst he still felt close to Ron G, Brucie B, Kid Capri / Funkmaster Flex, Lovebug Starski, there was an unresolved conflict in his sense of the recent past and didn’t eat sardines anymore (Now we sip Champagne when we thirst-ay). He was an East Coast rapper. The sardines he had been eating, back in the day, were almost certainly juvenile herrings. Tracing a narrative through aspirational capitalism in an updated Great American Songbook, they might even have been canned by the Snow family in Maine.

Eight years earlier, in Sardines, the funk/go-go Junk Yard Band, whose ‘hood was the Barry Farm government housing project in Washington DC, were more herring-celebratory (I got sardines on my plate / I don’t need no steak). Their juvenile herrings were an un-conflicted, anti-aspirational expression of community; a messianic, stick-to-your-roots, statement of a continuing bond between a band and its ‘hood, that could feed the 5,000:

Every mornin’ about a quarter to four (Sardines!)

The people are asking for more (Sardines!)

Oh Mamma, O what should I do? (Sardines!)

‘Do the go-go and give them some too!’

Back in Biggie’s world of gangster rap, although Tupac had been born in New York and probably eaten East Coast sardines, by the time he was 17 he’d moved to the West Coast, where the sardines he would have been on the road to giving up were Californian pilchards (Sardinops sagax or caerylius, depending on whether you go with the global fish species database FishBase or the United Nations’ FAO). Having said that, the Californian pilchard population had collapsed in the 1960s and the fishery was closed between 1967 and 1986. Numbers were building again in the 1990s, but this might explain why Tupac, gunned down in 1996, never got round to rapping on the subject.

We had to wait until 2015 and Kendrick Lamar’s For Free? (Interlude) for a West Coast dismissal of sardine-eating assumptions – Evidently all I seen was Spam and raw sardines. Raw plays with to an earlier mention of raw meat and doesn’t suggest he was buying from a fishmonger, where he wouldn’t have seen them anyway in 2015, because the fishery had been closed again. Meanwhile, the flaws in Enoch Snow’s business model are fully exposed in the current herring population failure in the Gulf of Maine.

Biggie Smalls, once been an active participant in a market which contributed to East Coast overfishing, was gunned down six months after Tupac. Heavy One (who loves to eat and was also known for keeping the beat with the demand-side sardine propagandist Junk Yard Band) had been gunned down in Barry Farm back in 1992. It’s hard to draw a conclusion from any of this. In the context of natural resource-based capitalism, celebrity commands a considerably higher price than herrings and pilchards. Or, alternatively, could sardines, re-conceptualised as aspirational, underpin sustainable fisheries?

So what is a sardine and where?

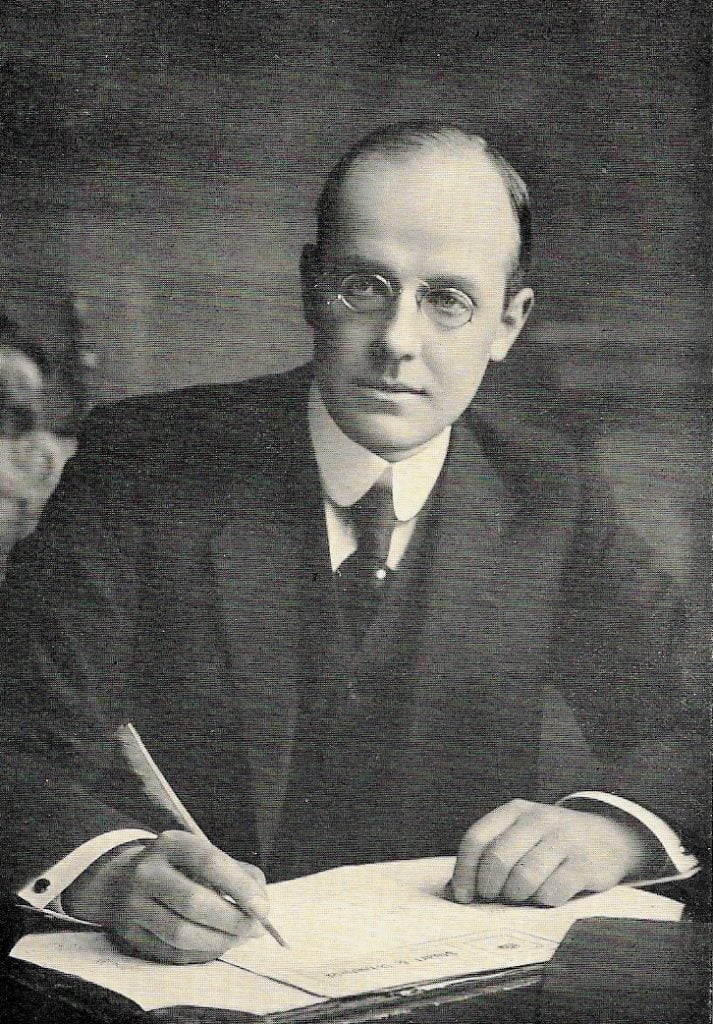

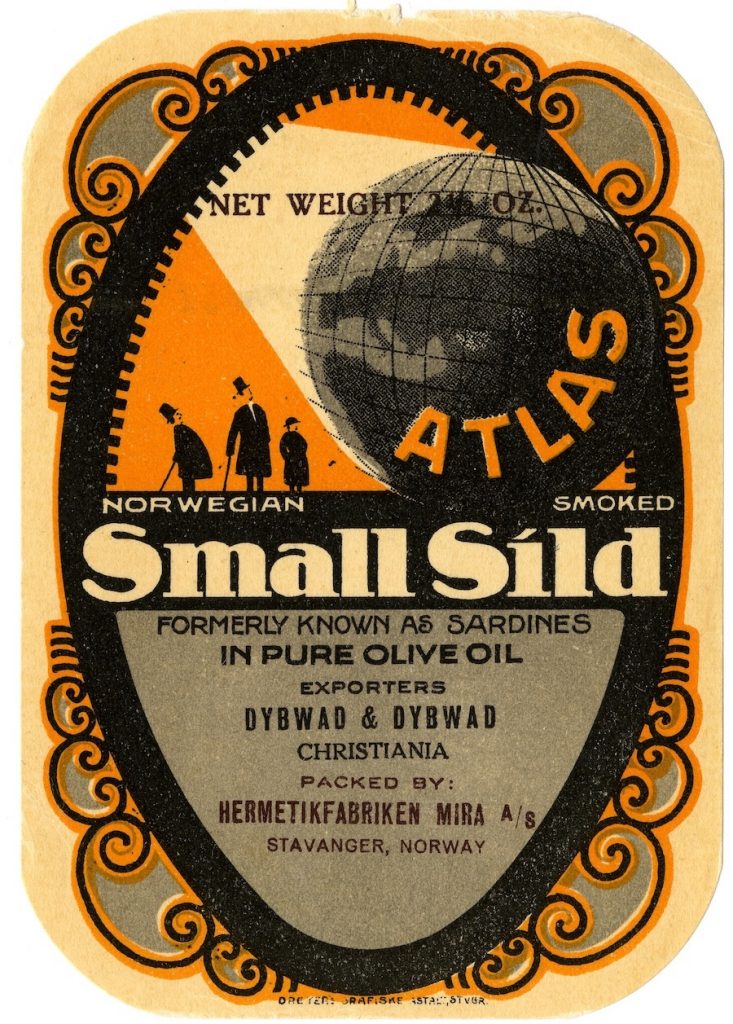

There was a time when almost any clupeid could be pulled out of the sea anywhere and canned as a sardine. Even the English loved sardines out of the can. They liked French and Portuguese sardines too, but Norwegian ones, imported by the Tyneside grocery entrepreneur Angus Watson as Skippers, were cheaper.

French and Portuguese canned sardines are juvenile Sardina pilchardus. Norwegian sardines are both smoked juvenile Clupea harengus (herrings/sild) and Sprattus sprattus (sprats/brisling), which often shoal together.

In 1911 the French went to court in a number of Europe countries to establish the principle that a canned sardine could only be a European pilchard. Angus Watson, who had played a key role in the development of the Norwegian sardine industry was drawn into the Great Sardine Litigation, which, in London, was finally settled in France’s favour in 1915.

Angus Watson on The Great Sardine Litigation

It was in the seventh year of the business that we became involved in litigation which caused much interest at the time, and became known as the ‘Sardine Litigation.’ To explain the issue fully it is necessary briefly to outline what the question involved really was, it being limited to the United Kingdom alone, and it may be mentioned here that the same issue was raised unsuccessfully by the French canners in one or more of the minor courts in France, In Washington, U.S.A., and in Victoria, South Australia.

The process of making sardines almost certainly dates back to the period of early Greece, when historians referred to this product as a dish prepared by the pouring of boiling olive oil over small tunny fish, after which they were served as a delicacy at the royal tables.

More than a hundred years ago the French nation began packing sardines on commercial lines, no doubt using the name ‘sardine’ because they first caught the fish off the coast of Sardinia. There is a diversity of opinion as to what fish was actually used, but there is little doubt that they were pilchards, a small fish which is scientifically known as the Clupea Pilchardus, being one of a small class of fish which are described as ‘Clupeoids’, because they collect their food by swimming through the sea with their mouths open, filtering the food through their gills from the sea-water.

The Clupeoids may be divided into three main classes – the Clupeoid Pilchardus, the Clupeoid Harengus and the Clupeoid Sprattus; the first including pilchards of various kinds, the second some twenty-six different varieties of herrings, and the third some six or seven different types of sprats. In some cases different kinds of small mackerel were also used for the manufacture of sardines, including a well-known one called ‘Chinchard’ which is caught in the Mediterranean. Included in this mackerel group is the red mullet, and some authorities consider that this fish was the first used in the making of sardines by the Greeks, the word being derived from the Greek word ‘sard’ meaning ‘red’, as for example in ‘sardine stone’, which is, of course, a red stone.

The French canners themselves at one time used several varieties of fish in their process of canning, but the pilchard was in later years generally claimed by them as the true sardine, although no fish has this name scientifically applied to it, the term being loosely used in different parts of the world to denote a number of varieties of small fishes. Indeed, there is caught in the Sea of Galilee, a small fish which is so named by the local fishermen. There is also a fish called ‘sardine’ caught off the coast of Peru and also in the St. Lawrence River. I write from memory, but I’m nearly sure that at the first Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace ninety years or so ago there were exhibited tins of sardines from Canada – caught in the St Lawrence – which certainly were not pilchards. This was – I write again from memory – proved by the catalogues of the Exhibition which were put in as evidence. I have not now the catalogues to verify this.

When the Norwegian industry became a formidable competitor to the French and Portuguese packs, they decided to attempt to limit by law the application of the name only to sardines manufactured from pilchards, and as the attempt to set up this standard was first made by them in Great Britain we were involved in testing the question through litigation.

The Norwegian canners were using for their process a small fish, extremely plentiful in the Norwegian fjords during the summer-time, called ‘brisling’ (a member of the Clupeoid Sprattus family), this fish owing the delicacy and richness of its flavour to a minute crustacea which is found in enormous quantities in the fjords and upon which the brisling feed. Here was an issue entirely after the heart of the lawyers: it was a very involved scientific question and there was no fixed standard applied by which it could be tested.

Broadly speaking, the case of the French canners, who were subsidised by the French Government, was that the term ‘sardine’ could only be legally applied to sardines made from pilchards. The Norwegian case was that the term was not applied to a fish (which was indeed true), but to a process of manufacture in which a large number of different fish were used.

One morning our Company was served with a summons to appear at the Guildhall in London to answer a charge under the Merchandise Marks Act of applying the term ‘sardine’ to a product which was incorrectly so described. At the time I did not regard the issue at all seriously, for I knew that we were carrying on an industry that had been conducted on the same lines without change since the late ‘seventies, and when our solicitors began the necessary trade enquiries there appeared to be ample evidence throughout the country with which to support our interpretation of the facts.

After an interval our defence was prepared, and a great deal of trade and scientific evidence on both sides was given at the first hearing. The issue was a long-drawn-out one, lasting more than three months, but at the end of that time a verdict was given in our favour on a technical point. It then remained for the French canners to renew their action if they desired to do so, and this they did again in the London Courts, when after a protracted hearing the verdict was given against the Norwegian canners. We decided to appeal against this decision, and a third hearing was begin at the London Quarter Sessions before Sir Robert Wallace. He gave an unqualified verdict in our favour.

But that was not the end of the case, for the French canners again brought the issue to the Divisional Court, as they had the right to do, and it came before Lord Reading (Lord Chief Justice), Mr. Justice Darling and Mr. Justice Avory. This fourth hearing took place in July 1915, each of the judges deciding in favour of the French canners, though Mr. Justice Darling expressed some doubt. There was no further appeal on this decision.

Although the various hearings were both tedious and exhausting there were several amusing interludes in the arid wastes of expert evidence given during the trial.

On one occasion a scientific witness was in the box, when Mr. Walter, K.C., our leader, rose to cross-examine him. He began by reading an extract from a text-book on the subject, without disclosing its title. The article conflicted strongly with the evidence that the witness had just given.

‘What is your view of that article?’ enquired Counsel.

‘It is sheer nonsense,’ replied the witness.

‘I gather you do not agree with the writer.’ said Mr. Walter.

‘Not at all,’ replied the witness, ‘he obviously has never given any study to the subject.’

‘Would you be surprised to hear that he claims to have expert knowledge on the question?’ queried Counsel.

‘I don’t care what he claims.’ said the witness, ‘I only know that he is entirely wrong in his conclusions.’

Counsel paused for a moment, and then handed a slip of paper to the expert in the box.

‘Look at that,’ he thundered, ‘ it is the receipt for the payment of this article, and you have signed it, for the article was written by you.’

The witness retired.

It is only fair to say that he had long forgotten the existence of this contribution, written years before.

Another expert witness was giving evidence, and Mr. Walter again rose to cross-examine him.

‘I understand that you claim to have an intimate knowledge of this subject,’ he enquired.

‘Yes, certainly,’ was the reply.

‘Well, then, will you tell the learned Judge how many links there are in the spine of a pilchard?’

The witness hesitated, and then frankly admitted that he did not know.

‘Very well, let me try once more and see what you know. How many scales are there on the back of a herring?’

Again the witness confessed his ignorance.

‘You surprise me,’ said Counsel, ‘Then can you tell me the approximate number of eggs in the roe of a mackerel?’

‘I cannot give a true estimate as to that,’ said the witness.

‘And you come here claiming to be an expert,’ said Mr. Walter, throwing down his papers and resuming his seat.

Another witness for the French canners was the managing director of a series of stores, who asserted that the young pilchard alone was the true sardine. Whilst he was giving evidence in chief we obtained a tin of sardines from one of his stores near the court, and on its being opened by one of our scientific witnesses he declared the contents to be small herring, though labelled sardines and with a French label. During his cross-examination by Mr. Walter the latter handed the opened tin to him and asked if he – the witness – considered they were correctly described as sardines. He replied in the affirmative, and on being informed by Mr. Walter they had just been purchased at one of his stores and the contents were young herring, he was obliged to admit that he did not know the difference, and he thought his Company were right in selling them as sardines.

It should be added that Counsel for the French canners disputed the contents as herring but did not call evidence to support this, whilst our scientific witness could not be shaken on the point when he gave evidence.

I always found dialogue of this description interesting and amusing, until I remembered that it was costing us about £500 a day!

The Magistrate who took the first case died before the second hearing: Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett (the father of the distinguished Counsel of the same name who died recently) died during the second hearing: Sir John Dickinson, the chief Magistrate, who followed him, died shortly after the resumed hearing: one of the Counsel briefed committed suicide: one of the witnesses died a violent death.

I was in the witness-box on four occasions under cross-examination for seven hours, and was glad to escape with my life. I have suffered from what the doctors call ‘migraine’ at intervals ever since.

This issue, which was continued for four years, and which involved, in all, the hearing of evidence from more than a hundred witnesses, at a cost to ourselves of some £50,000, settled the matter finally. The Norwegian canners contributed £20,000 towards the costs, and the Norwegian King very graciously decorated me with the First Class Order of St. Olaf in recognition of this long and trying litigation.

Curiously enough, this action had the effect of very considerably increasing our sales, and except for the fact that it made great demands both on my time and energy, the outcome of it could only be regarded as favourable to our business. None-the-less, I was more than satisfied when the issue was finally disposed of.

From My Life by Angus Watson (1937)

The court’s 1915 ruling underpins the current European Union regulation:

In the case of hermetically sealed canned sardine and sardine-type products, only fish of the species Sardina pilchardus can be marketed (labelled) in the EU as ‘Sardine’. Sardine-type species can only be marketed (labelled) under a trade description consisting of the word ‘Sardines’ joined together with the scientific name of the species. A description of these marketing standards, and the species of fish subject to them are found in the Commission Regulation (EC) No 1181/2003 of 2 July 2003 laying down common marketing standards for preserved sardines.

But it stopped there. The French tried to extend their success, but, just as the European pilchard has remained European, so has the ruling. North American East Coast sardines are Clupea harengus and elsewhere they can be various kinds of Sardinops or Sardinella. They can even be the Australian Sandy Sprat, the Perth herring, the red-eye round herring…

And, of course, Norwegian sild and brisling can be sold anywhere outside the EU as sardines. In Australia, the love of food from the ‘home countries’ is such that, in a supermarket in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales I came across John West tins of Wild Scottish Sardines, just hinting at sportsman in his waders, heading out to sea with his fly-fishing tackle…

Commission Regulation (EC) No 1181/2003 defines preserved sardine-type products as:

Products marketed and presented in the same way as preserved sardines and prepared from fish of the following species: (a) Sardinops melanosticus, S. neopilchardus, S. ocellatus, S. sagax, S caryleus; (b) Sardinella aurita, S. brasiliensis, S. maderensis, S. longiceps, S. gibbosa; c) Clupea harengus; (d) Sprattus sprattus; (e) Hyperlophus vittatus; (f) Nematalosa vlaminghi; (g) Etrumeus teres; (h) Ethmidium maculati; (i) Engraulis anchoita, E. mordax, E. Ringens; (j) Opisthenema ogilinum.

John West was formed in 1961, out of a merger of three Unilever companies including Angus Watson & Co. Following EU regularions, it has recently taken to labelling its cans Norwegian Sardines (Sprattus sprattus). Meanwhile, in the UK, working with the popularity of Mediterranean and Portuguese beach restaurant barbecue-grilled fish, once-derided fresh pilchards now appear on fishmongers’ slabs as Cornish sardines.

Digression upon Angus Watson’s My Life

My grandfather gave me a signed copy of My Life by Angus Watson. It’s one of those books which probably only survives in signed copies. It sat unread on various of my bookshelves for maybe 40 years. One day, my wife was insisting on a clear-out of unwanted books and I put it in the crate for the Oxfam shop.

It was several months later that we were visiting the Norwegian Canning Museum in Stavanger. Suddenly, I was looking at an exhibition text telling the story of Angus Watson, grocery entrepreneur from North East England, who had helped transform Stavanger’s (herring and sprat) sardine industry. I felt sick. I swore I would never throw away another book.

Years later, searching for another book on our overloaded shelves, I came across it, hiding behind a pile of other volumes. I had put it in the crate, but then, obviously, I had thought again.

Angus Watson had been a Methodist teetotaller, like my grandfather. And my grandfather, concerned about some of my personal choices, had given me the book precisely for this reason. He had gone to the same Rothbury chapel as Watson and it had almost certainly been Watson who, in 1938, had found a berth for my dad on a merchant ship, when he’d had been expelled from Gosforth Grammar School for lunchtime drinking and billiards beneath Newcastle City Hall.

There is such a thing as redemption.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Simon Lloyd for drawing attention to the herring / sardine significance of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel. The last time I had seen Carousel was a production by Prudhoe Community High School in which Simon Lloyd’s good friend – and my son – Sam Rigby, played violin. At some point in the late 1990s, I think it was before I began to research herrings properly. That’s my excuse, anyway, for not noticing it before.

Meanwhile, I would like to thank Sam for drawing my attention to the sardine-related work of Biggie Smalls, Junk Yard Band, Kendrick Lamar and Beastie Boys. He also mentioned the Jamaican artist Popcaan, but – with no idea whether Jamaican sardines are imported herrings, Pacific pilchards, European pilchards, sprats or even a Sardinella brasiliensis, it seemed a step too far.

Big thanks to Piers Crocker of the Norwegian Canning Museum.

It’s sadly too late to thank my grandfather for Angus Watson’s My Life.