The rise and fall of the ‘Groote Visserye’, its role in the Dutch War of Independence and in various wars with England and Scotland

DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

On the very first page of his Short Description of the Herring Fishery in Holland (1639) Mynert Semeyns locates the momentous year the first herring was caught and eaten by a Dutchman. It was 1163 AD.

Given the once-healthy inshore population of the Zuyder Zee, this is unlikely. Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn’s Town Atlas of Holland (1634) has Dutch fishermen participating in the Herring Fairs of Skåne in Southern Sweden before the end of C12th, but fishermen and merchants seem to have been active in Scotland and the Yarmouth Herring Fair from much earlier.

Some Dutch towns were members of the Hanse, which controlled the Skåne fishery. They clearly drew on Hanseatic experience in building their own herring fishery off the coasts of Scotland and England.

After the Skåne fishery theirs was the second to justify the Comte de Lacépède saying The herring is one of those products, the use of which decides the destiny of empires. (Histoire Naturelle des Poissons, 1798).

In English, the great sourcebook is Anthony Beaujon’s The History of Dutch Sea Fisheries: Their Progress, Decline and Revival, Especially in Connection with the Legislation in Earlier and Later Times (1884). His story is of a great industry, built on quality control and strangled by regulation.

I: Die Groote Visserye

Edward I

Beaujon notes an order of England’s Edward I announcing in 1295, ‘that many people from Holland, Zealand, and Friesland, who are our friends, will shortly come and fish in our sea off Yarmouth.’ He commands his subjects to treat them civilly, neither molesting, robbing nor plundering them.

Kings of England have not been alone in offering friendship for money, but permission was important. The fishing grounds were close to the English coast and catches had to be salted on shore. Unlike at Skåne, however, where the Hanse took strict control of all sales, the English herrings were then theirs to trade.

Innovation

The first large herring net was made at Hoorn in 1416. The Dutch were building larger fishing boats – the celebrated herring busses – because at some point in the C14th someone, possibly the semi-mythical Willem Beuckel, had developed innovative techniques of gutting, salting and barreling the herring at sea.

At Skäne the Hanseatic League maintained control by insisting on land-based salting, but there the fishery was concentrated on a much smaller stretch of coast. Salting at sea, the Dutch may have naively hoped they would no longer need the friendship of foreign kings, but they also knew that marketable quality depended on the speed with which herring was gutted and salted.

The Dutch built on the quality control regulations of the Hanse, concerning themselves with the details of how the herring was packed in barrels, the best kinds and proportions of salt, the dates between which herring in prime condition was caught and much more.

Die Groote Visserye

Following the sequential arrival of different herring populations down Scotland’s and England’s North Sea coast, they called it Die Groote Visserye, The Grand Fishery. Its marvelled growth was associated – both in their own minds and in the minds of their competitors – with the buss.

With each catch preserved and barrelled on board they could carry on fishing until the much greater capacity of the buss was filled. There was a premium available for the first herrings of the season, however, which gave rise to the ventjager or sale-hunter. Each operating as a tender to ten busses, these were small, fast boats, allowed to operate in the early part of the season.

They bought their herrings from the busses and competed to get the barrels to the market.

Regulation

The Dutch were undoubtedly enthusiastic herring regulators. In 1424 John III, Duke of Bavaria and Count of Holland, also known as John the Pitiless, issued edicts on the fabrication and marking of barrels and on the curing of the fish.

He was poisoned the following year, but it may have had more to do with his pitilessness than his interest in herring.

In 1439 Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, son of Pitiless’ brother-in-law John the Fearless, took up the cause. He issued an edict on Last Money – a tax on each last or 12 barrels – gathered towards the cost of a naval convoy to protect the herring fleet.

Other edicts prohibited selling herring in foreign ports or salting it before St Bartholomew’s Day (August 24th ) and specified the kinds of salt that could be used.

Among other claims to fame, it was Philip’s Burgundian army which caught Joan of Arc and he sold her to the English for £10,000. This only makes the cut in a herring encyclopaedia because of the Battle of the Herrings (1429), at which Sir John Fastolfe (Shakespeare’s Falstaff) fought off combined French and Scottish forces to bring Lenten supplies to the English army at the Siege of Orleans.

Back to fishing regulation, the top herring man was Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. On his abdication tour of 1556, he actually took time to visit the supposed tomb of Willem Beuckel.

37 years earlier, he had inaugurated a systematic approach to fishery legislation. He made obligatory the branding of barrels to establish their quality. Each barrel would bear the marks of both the cooper who made it and the shipmaster who filled it.

New barrels were to be used each time and cure masters were appointed in every fishing town and village to certify them. Only refined salt or moor salt could be used. Quality certificates were required and the amounts to use for the different kinds of salt were specified.

Charles V legislated on the way herring should be packed in the barrel, that different qualities of herring should be packed in different barrels and ones filled with herring caught before St James’ Day (July 25th) should be branded with the scallop shell.

Dealers were required to make a declaration of the quality of herring contained in a barrel. At sea, the salted herring was to be moistened with seawater every fortnight. Inshore herring, caught in the estuary of the River Y was not to be salted for export, but only used for home consumption and buckling.

Helped by the less attentive approaches of others, the Dutch rapidly achieved an enviable reputation for the quality of the herring their merchants sold.

II: The Republic – War and Regulation

Wars, Piracy & Revolution

The busses were seen as the training grounds for Holland’s rise as a naval power, both by the Dutch and their competitors. But War isn’t good for herring fishing and the problem was compounded by the distance the herring fishing grounds were from the Dutch coastline.

Scotland and later England objected to so much apparent wealth being taken from their waters. At war with the French, the Dutch fishing fleet was also vulnerable to Dunkirk privateers – it’s been said that the golden age of piracy saw more fish looted than gold and silver.

As pioneers in on-board salting and barrelling, the Dutch presented the privateers with a ready-packed commodity.

Last money, created to finance the protection of the busses, was increasingly being used for other imperial needs and the fishing fleet convoys were becoming old and ill-equipped. The privateers were usually happy to offer safe conducts for money, but the ship owners then resented still having to pay last money, which the Holy Roman Empire continued to collect – along with additional taxes.

William the Silent, Prince of Orange, appointed Stadtholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrecht in 1559, was strategically lenient in the collection of herring taxes.

Ferdinand Alvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alva, on the other hand, sent to the Netherlands to put an end to Protestant heresy eight years later, further increased the taxes, enforced loans from the ship owners, conducted mass executions and, if engravings are to be believed, ate babies.

He may not have said much, but William was popular and led the Dutch Revolt, which eventually brought about the Dutch Republic.

Dutch Republic

A Dutch herring committee is first mentioned in 1548. Responding to leniency in taxation as well as generous loans, by 1575 the Deputies of the Herring Fishery were agreeing to levy last money themselves. In return they were given a practical voice in the spending of it.

The convergence of interest between state and fishing industry saw the further growth of the herring trade. Increased legislation and codification came with the territory.

The cured herring business was recognised as the chief industry of the country and principal gold-mine to its inhabitants (Resolutions of the States of Holland, 1581). Calvinism, The Republic and the herring industry worked together seemlessly.

The Dutch catch more herrings, and prepare them better, than any other nation ever will, and the Lord has, through the instrument of the herring, made Holland an exchange and staple-market for the whole of Europe. (Meynert Seymens)

The Growth of Subsidy

In the 1580s the herring fishery was granted immunity from the excise duty on salt. Possibly to counter abuse of the privilege, this was converted into an annual payment of 6,000 florins a year. An extraordinary subsidy of 20,000 florins was made to the Fisheries’ Commissioners, out of which they were expected to fund their own men-of-war. By the 1650s this had grown to 30,000 florins a year.

III: Grotius and Selden

The Fishery

Starting at Midsummer in the Shetland Islands and off Fair Isle, The Grand Fishery moved to Buchan Ness in September and then down the coast to Yarmouth, where it operated from 25th November to 1st January. Each buss made three voyages per season, catching an average of forty lasts.

It has been estimated that 1,000 Dutch boats were involved in the fishery in 1560, 2,000 by 1620, when it yielded an annual revenue of two million guilders and supported the employment of 450,000 people (John de Witt, A Representation of the Wholesome Political Grounds and Maxims of the Republic of Holland and West Friesland, 1669).

In 1620, however, the Dutch forbade fishing off Shetland, Ireland and Norway. In theory, this was because the being herring caught was inferior. In reality, it was an attempt to meet the complaints of James I of England, VI of Scotland.

Even before coming to the English throne, the Stuarts had taken considerable interest in the herring. James’ grandfather had conducted a half-hearted war with the Dutch over it in the 1530s.

Grotius & Selden

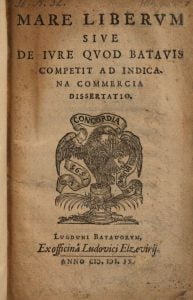

The Dutch jurist Huig de Groot or Hugo Grotius had been brought in by the Dutch East India Company to defend the seizing of a Portuguese ship and its cargo off Singapore in 1603. He developed the legal principles further in 1609 with the publication of Mare Liberum or The Freedom of the Seas.

He argued that the sea was international territory and that, therefore, it was legitimate to take actions that broke up trade monopolies instituted by other nations.

James I & VI saw the concept of international waters as a challenge to his dominion of them and issued a Proclamation Touching Fishing insisting no foreigner was to be allowed to fish in British seas without paying for a licence from the king.

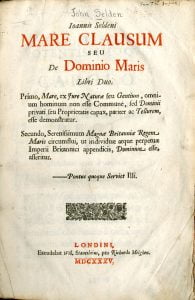

James was ultimately only half-hearted in pursuing his claim and prohibited the publication of John Selden’s Mare Clausum (The Closed Sea), written c 1617 and arguing for the principle of territorial waters. It was not a new concept – in the C16th and C17th, Spain considered the whole of the Pacific Ocean closed to other European powers.

Selden, however, coined the legal principle and James’ son, Charles I, used it to press English and Scottish claims more forcefully. The ban on publication was lifted and Mare Clausum was published in 1635.

IV: Too Many Fish – Monopoly and Supply

Decline

Dutch dominance of the herring trade was built on innovation, quality control and fiercely-held monopolies. They could command a price because they offered a reliable, premium product where the smell of their competitors’ products had become a comic commonplace.

Ultimately the sheer availability of herring worked against them, but success was also problematic.

Holland’s rapid economic growth – and the sense of the role herring played in it – made its fishing fleet a target. The first serious check to the Dutch fishery came with the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Even though they won as many battles as they lost, the disruption was enough.

In 1653 the busses were banned from sailing out of fear of the British naval fleet. In 1665 sailing was banned even before England had declared war. The fishing fleet hardly got out at all in the War of the Spanish Succession. The Peace of Utrecht in 1713 simply came too late.

They had already begun to reassess the quality of their inshore herring and the buss fleet went into decline. In 1736 there were only 300 ships, by 1779 only 162.

The Great Fishery had set the standard against which a barrel of salted herring should be judged. In the long term, once other nations grasped this, it was impossible for the Dutch to protect their trade monopolies from more flexibly regulated competition.

Clearly influenced by Adam Smith’s dodgy analysis of the herring trade in The Wealth of Nations (revised edition, 1784), Beaujon argues that over-regulation, protectionism and subsidy were at the heart of Holland’s failure to adapt to new realities.

In the 1850s the Dutch began to deregulate and abolish subsidies, but by this time the British fisheries had taken their place.

Books

The Herring and the Herring Fishery by JW de Caux, London, 1881

The History of the Dutch Sea Fisheries by A Beaujon, London, 1884

The Royal Fishery Companies of the Seventeenth Century by John R Elder, Glasgow, 1912

The Herring; its Effect on the History of Britain by Arthur Michael Samuel, London, 1918

The Herring and the Herring Fisheries by James Travis Jenkins, London, 1927

See also

- BEUCKEL, Willem

- BOHUSLÄN FISHERY

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BUSS

- DIVINE PROVIDENCE

- DUMAS ON HERRING

- ENGLAND’S PATH TO WEALTH AND HONOUR

- FASTING

- GERMAN SPIES

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- HERRING INDUSTRY BOARD

- HERRING LASSES

- ICELANDIC FISHERY

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- LOCKMAN’S VAST IMPORTANCE

- QUOTAS

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- SALT

- SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS

- SMITH, ADAM: WEALTH OF NATIONS

- SWIFT, JONATHAN

- VENTJAGER

- WEDGWOOD

- ZUYDERZEE