An account of early underachievement, overdue triumph and eventual decline in both England and Scotland, featuring kings, economists and fishermen

BRITISH FISHERY

When, in his Histoire Naturelle des Poissons (1798) the Comte de Lacépède’s wrote, The herring is one of those products, the use of which decides the destiny of empires, he may well have had the combined English and Scottish fisheries and the British Empire in mind as the third example. If they’d tried harder they could have been the first or at least the second.

From an early start in the trade and an overwhelming natural advantage, it took nearly 200 years of incompetence to oust the Dutch as top herring nation. They only just got in under the wire for any kind of inclusion in Lacépède’s thinking.

By 1798, if he did indeed have them in mind, it was probably more a case that, after a series of herring-related Scottish-Dutch and Anglo-Dutch wars, he could see the way things were going. From the C16th to the C18th the British were actually better at empires than the use of herring.

The major British fishery considered here involved the same fish as the Dutch Grand Fishery. Around the coast of the British Isles, there are also a number of inshore herring populations which have never shown much interest in empires.

I: After Cerdic – The Medieval Fisheries

Cerdic the Saxon

The English herring fishery was, by tradition, founded not long after 495 AD when Cerdic the Saxon landed on Cerdic Sands (or Cerdic Shore), near what would become Great Yarmouth. The association with Cerdic’s landing is important, because from his loins sprang the Kings of Wessex and the subsequent English royal line.

There are nitpickers. Some say that Cerdic is a Romano-British name. Some say he landed in Hampshire. As a direct descendent of the Teutonic god Woden, he was, of course, capable of accommodating several alternate realities. He died in battle shortly after landing and his son Cenric carried Woden’s DNA into the succession of English royal houses.

Yarmouth & the Early English Fisheries

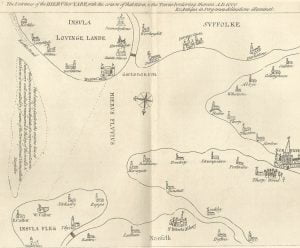

The Romans, we are told, looked upon the herring as a dainty dish, and their knowledge of it is believed to have been obtained from their soldiers on the Eastern Coast at a mural encampment called Garianonum, that is ‘the mouth of the Yare.’

The Herring and the Herring Fishery, JW de Caux (1881)

De Caux, like so many herring historians, is light on attribution: he doesn’t say who told us. Gariannonum may have been at Caister on Sea, north of Yarmouth. It may have been at Burgh Castle. The coastline around the mouth of the River Yare has changed hugely over the centuries and the sandbank upon which Yarmouth was eventually built only began to emerge at the time of the birth of Christ.

At some point after the arrival of Cerdic a herring fair was established at Yarmouth. Attracting fishermen and traders not just from England, but from France, Normandy, Flanders and Holland, it ran from Michaelmas (20th September) to Martinmas (11th November).

In his History and Antiquities of Great Yarmouth (1772) Henry Swinden writes that St Bennet’s Church was built in 647 and a godly man placed in it to pray for the health and success of the fishermen that came to fish at Yarmouth in the herring season.

This suggests a herring fair was held at Yarmouth from the early C7th at least – considerably earlier than the one at Skänor in Southern Sweden, from which the English and the Scots were sometimes banned for bad behaviour.

The known fishing grounds were largely inshore; fishermen had to salt their fish and dry their nets on land; they had to buy provisions; they brought tradable goods with them. A lot of beer had to be brewed. It was a natural market and you only had to put up with the wild disorder for a couple of months.

Yarmouth’s fair shaped the laissez-faire beginnings of an internationally significant English herring fishery.

By 670, the Abbey at Barking was levying ‘herring silver’, a tax on herring, probably also paid in fish. In 709 herring is mentioned in the accounts of the Monastery of Evesham, nearly 200 miles from the fishing grounds. Salted in barrels or smoked its value was reliable enough to be used effectively as currency.

Yarmouth After the Conquest

The Normans placed the Yarmouth Herring Fair and the fishery under the control of the Barons of the Cinque Ports. The relationship was not happy and the town worked to undermine it. King John transferred some rights back in return for naval service.

Henry III started calling it Great Yarmouth, but it was Edward III who really shifted things back in the town’s favour. Having already returned the bulk of Yarmouth’s rights, with the Statute of the Herrings of 1357 he officially concentrated the market there.

The statute confirmed a free right of fishermen and traders to buy or sell to and from anybody they chose, whilst fixing a maximum price.

Edward codified what had long been English policy – back in 1295 Edward I had been commanding his subjects to be nice to the fishermen from Holland, Zealand and Friesland, ‘who are our friends’. As long as everyone paid their dues, the monarchy was happy to see a reasonably free international fishery.

Peter Chivalier

English legend had it that the salting of herring was invented by a Peter Chivalier at some point in the C12th and somewhere in the West Country. As with the Dutch Willem Beuckels there may have been a basis for this in some lost history, but, quite apart from the long history of fish salting, the C11th Domesday Book was already recording three salt pans Gorleston, just to the south of Yarmouth.

Historically, the reputation of English salt-cured herring was not strong, so whatever the techniques were that Chivalier brought to the trade, they were either lost or not worth preserving.

Early Scottish Fisheries

As with England, Herring will have been fished for on the coasts of Scotland from early times, but the first speciific mention is not until 1138, when David I granted fishing rights to the Abbey of Holyrood. The early Scottish herring fisheries were concentrated in the firths of the Forth and the Clyde.

Coull (The Sea Fisheries of Scotland, 1996) sees the Scottish feudal system as having acted against the development and modernisation of fishing from the C15th. Traditionally the fishermen had no rights in their land and houses and therefore no access to capital.

The lairds were responsible for investing in new boats and their willingness to do so depended on how much spare money they felt they had. There was tendency to conservatism and to an investment just in the small boats that were suited to the firths.

Scottish kings, on the other hand, were resentful observers of the hugely successful Dutch herring fishing off in what they considered to be Scottish waters.

By the 1470s James III was encouraging the building of Dutch-style herring busses. Between 1532 and 1541 James V went to war with the Dutch over his insistence on a 14 mile limit within which they were not allowed to fish.

Coull identifies the advantages the Dutch held over the Scots: technique, capital, organisation and control of the market. Pretty much everything, in fact, but the fish.

II: Herring Mad – The House of Stuart

Looking Across the Water

From James III onwards, the House of Stuart was herring mad. To understand this – and the way it played out in the C17th – it is necessary to look, with the Stuart kings, across the water at the rapid growth of Dutch sea power, wealth and empire.

Dutch self-promotion itself placed the herring at the heart of the divine providence on which the nation’s wealth was founded. It brought trade and riches and provided a school for sailors.

God drove the herring towards their nets, whether this was off the Shetland Islands, off the Hebrides or working down the North Sea coast.

The unity of purpose, which the Dutch nation brought to the herring trade, was the grateful response of a chosen people.

James VI & I

On the death of Elizabeth I, in 1603 James VI of Scotland became also James I of England & Ireland. Six years later the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius published Mare Liberum, asserting the principle that all seas were international waters, open to trade by all.

Grotius doesn’t mention fishing, but James understood that this was included. He issued a proclamation forbidding foreign fishermen from all British coasts unless they paid for the appropriate licences.

The Dutch pointed to treaties agreeing to unimpeded and unlicensed Dutch fishing in English seas, but James was having none of it. At the end of the day, however, he was a cautious king.

In negotiations stretching over the rest of his reign, the Dutch resolutely pursued a policy of delay and limited compromise. To counter Grotius, James encouraged John Selden to write Mare Clausum, asserting the principle of territorial waters, but then wouldn’t allow it to be published.

Knowing it was something James wanted to hear, during his reign pamphleteers constantly pointed to the riches a herring buss fishery would bring. In prison, Sir Walter Raleigh attempted to curry favour, arguing the case in Observations Touching Trade and Commerce, which was presented to the king in 1605.

Two years later William Camden updated his national epic Britannia to include an acknowledgement of the goodness of God towards us in the herring fisheries off the British coast – a divine providence that was being falsely claimed by the Dutch.

In 1614 Tobias Gentleman published England’s Way to Win Wealth, giving a detailed account of the Dutch fishery and the wealth derived from it.

Encouraging the demand side, in 1619 James forbade the eating of flesh during Lent – Protestant England’s lack of interest in fasting affected the home market for herring. On the supply side, he tried to establish a fishery on the Isle of Lewis, granting patents to merchant adventurers. The Earl of Seaforth, who owned Lewis, was more interested, however, in working with the Dutch.

Even though Seaforth was happily granting the Dutch nearly all his own people’s traditional fishing rights and privileges, the islanders of Lewis still set about the task of dissuading James’ adventurers – in a number of cases terminally.

Charles I

Successor to the Stuart thrones, Charles I inherited James’ interest in herring, but not his caution. In trying to establish a herring buss fishery he wrote to Scotland’s Estates, This is a worke of so great good to both my kingdomes that I have thought it good by these few lynes of my owne hand seriouslie to recommend it unto you. The furthering or hindering of whiche will ather oblige me or disoblige me more than anie one business that hes happened in my tyme.

He told the Privy Council, Among other good services done be you for the publict good of that our ancient kingdome we will accompt this one of the greatest.

Charles’ vision of how it would transform his nations’ wealth, trade and naval power was not shared by the lairds and burghs of Scotland. He ordered Seaforth to kick out the Dutch and announced a grand plan for an Association for the Fishing, a joint stock company with rights in English, Scottish and Irish waters.

There would be 200 busses of between 30 and 40 tons following the herring around the British coast from June to the end of January. The Scots were focused on their own inshore fisheries and as keen to keep out the English ‘strangers’ as the Dutch. After much haggling an agreement was reached in 1632, largely giving Charles what he wanted.

If buss building enthusiasm was limited, it declined further as Dutch men of war and privateers from Dunkirk took the few that were completed or bought from Holland in the first place.

In 1635, Charles ordered the publication of Selden’s Mare Clausum. He sent a fleet of 26 ships into the North Sea to enforce recognition of his dominion. The following year he issued proclamations forbidding foreigners from fishing without a licence. The islanders of Lewis were told that the Association’s adventurers were neither strangers nor foreigners.

The Earl of Northumberland was sent to English fishing grounds with 12 ships and 300 licences signed by the king. The Scots decided they wanted a year or so to think about the best and most faisable way to collect fees.

The Dutch sent Admiral Van Dorp to counter Northumberland’s threat, but he arrived too late. Feeling he didn’t have the authority to engage the English fleet, he sailed home to public censure.

In 1637 the Dutch sent a larger convoy to protect their fishing fleet and Charles backed down. A successful herring fishery would fill the coffers of the nation, but he couldn’t achieve one without the strong navy it would ultimately finance and sustain.

He’d been trying to address this problem for three years, levying peacetime ‘ship money’ not just in the coastal towns, which were used to it and could see the benefit of naval protection, but in inland counties where they weren’t and couldn’t.

By 1636 it had become clear to England’s propertied classes that the king saw ship money as a permanent tax. Their resentment of this was one of the key causes of the English Civil Wars, the pressures of which then distracted Charles from his pursuit of the herring.

Other factors applied in the build up to the Civil War and it is not known to what extent, as he laid his head on the executioner’s block, Charles reflected on the herring and its role in his misfortunes.

The Protectorate

Oliver Cromwell wasn’t necessarily a herring man, but he built up the English navy, which under Admiral Blake fought the first Anglo-Dutch War (1652-54).

The English won the Battle of the Kentish Knock. The Dutch won the Battle of Dungeness. The English won the Battles of Portland, the Gabbard and Scheveningen. But the Dutch succeeded in lifting the English blockade of their ports.

By the end of 1652, the people of Yarmouth were already complaining to Cromwell’s General Monck that they’d lost £200,000 and Not three boats are now preparing to go forth fishing, where 150 sail used to be making ready at this season.

In addition to the Dutch, English fishermen were having to put up with Prince Rupert’s small Royalist navy and the usual privateers from Dunkirk and Ostend. The conclusion of the war, which had devastated both British and Dutch herring fleets, left matters unresolved.

Charles II

If Cromwell’s Protectorate had offered little protection to its fishermen, it had offered even less encouragement to the observation of religious fasts. A true Stuart, after the Restoration Charles II outdid even his grandfather: a proclamation of 1662 encouraged the observation of Lent and throughout the year Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays were to be fish days.

To England’s Protestants it smacked of popery, but to Charles, Catholicism and a strong herring fishery were complementary virtues. A man on a mission, he announced an intention to give £200 to anyone who built a herring buss by the following June.

It took him nearly three years, but in March 1664 he established two Corporations for the Royal Fishery – learning from his father’s struggles, he gave Scotland its own. He made his brother James Governor of the English corporation.

Samuel Pepys was himself a member of the council he described in his diary as being made up of Several other very great persons, to the number of thirty-two. By July, however, Pepys was finding the company generally so ill-fitted for so serious a worke that I do much fear it will come to little.

By September his diary records, After dinner to Whitehall, to the Fishing Committee, but not above four of us went, which could do nothing, and a sad thing it is to see so great a work so ill followed, for at this pass, it can come to nothing but disgrace to us all.

To the charge of incompetence, Pepys was soon adding more than a suggestion of corruption, but fortunately all of the Corporation’s records were destroyed in London’s Great Fire.

The Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1665-67 and 1672-74), together with the five years of hostilities between them, finally did for the Corporation. Conflict discourages investment, but there was also public suspicion of James, whose conversion to Catholicism had became public in 1673.

It turned out Charles, the great herring promoter, was in cahoots with Louis XIV and, for French support, had been secretly promising his own public conversion and more. The Third Anglo-Dutch War went even worse than the Second. Parliament insisted on peace without any benefits to the herring industry at all.

The Corporation reorganised and tried to raise more capital, but gave up when Charles died in 1685. The parallel company Charles had set up in Scotland had already abandoned fishing – although it managed to continue collecting taxes until this was noticed in 1690.

The Last of the Stuarts

James became king on his brother’s death, but didn’t last long enough to do anything of importance for the herring fisheries.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought in William and Mary. Stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands as well as King of England, Ireland and Scotland, William can be forgiven a lack of commitment to the Stuart herring cause.

Queen Anne usefully reorganised herring laws, bringing regulations on the quality of curing salt and introducing bounties to encourage exports, but that was about it.

The Stuarts’ huge ambitions for the herring industry didn’t come to much, but the struggle they launched broke the back of the Dutch fishery. They can be credited with clearing the way for the eventual rise of the British herring fleet – although it still took pretty much until the C19th to get there.

III: The Wealth of Nations – The C18th and C19th

Recovering Credit

1718, early in the reign of George I, saw An Act for recovering the credit of the British fishery in foreign parts, the title speaking to Britain’s other herring problem. The Dutch may have been weakened, but the reputation of English and Scottish curing was poor.

Poor salt, poor salting, relaxed approaches to when catches were salted, the use of thumbs rather than knives for gutting, bad barrels, bad barrel-packing: the complaints were general and widespread.

There was an export trade but it underachieved. For red herring (ungutted, heavily salted, heavily smoked and very much associated with Great Yarmouth and the East Anglian ports) there was a good market in the Mediterranean. The huge European opportunities in the quality end of the white herring market, however, were mostly ignored.

Red herring keeps well in hot climates and a market for it survives in Italy, Greece and Egypt. Some argued the fish off Scotland’s West Coast weren’t suitable for good red herring, but the fishery there was well placed to supply the slave plantations of the West Indies, where quality control wasn’t a major concern.

The Scots rose the the challenge and red herring remains in the culinary traditions of the Caribbean. It’s also still eaten in Ghana – possibly from its being a saleable English commodity on the first leg of the slave trade triangle.

At the same time, the Scottish fisheries addressed the white herring problem earlier and more consistently than the English. From 1710 onwards their curers slowly broke into the important Hamburg market, where the weakened Dutch found it difficult to maintain the monopolies they had negotiated in better times.

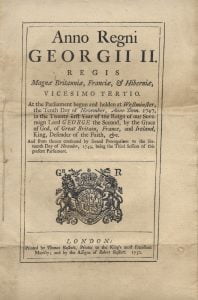

George II raised the question of the herring industry at the opening of Parliament in 1749. The Society of the Free British Fishery was established with Frederick, Prince of Wales, as its Governor.

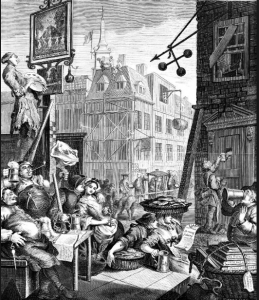

The Society appointed John Lockman, The Herring Poet, as Secretary. Beer Street, Hogarth’s print of 1751, shows a couple of fishwives with Lockman’s New Ballad on the Herring Fishery. Other notable works include The Shetland Herring and the Peruvian Gold-Mine.

Lockman had his accusers and he accused them right back, sometimes in verse. In cultivating his literary reputation he was known to give away pickled herrings along with his poems and he may not always have paid for it. But there were others more venal. The Society lasted until 1772, when it went the way of previous attempts.

The Wealth of Nations

The government’s fishing acts of 1750, 1753 and 1755 introduced, then modified a system of bounties on the building and fitting out of herring busses capable of extending the range of the fleet. On the back of the subsidy they enforced improved regulation.

In Book 4 of The Wealth of Nations, published in the revised edition of 1784, Adam Smith weighs in against the whole principle of subsidy. The bounty to the white-herring fishery is a tonnage bounty, and is proportioned to the burden of the ship, not to her diligence or success in the fishery; and it has, I am afraid, been too common for the vessels to fit out for the sole purpose of catching, not the fish but the bounty. He was clearly pleased with the quip.

Smith ignores the fact that the market, in which he held such faith, had spent over 200 years conspicuously failing to match the interventionism of the Dutch state. For most of the C18th Sweden and Denmark did much better.

Smith argues support for the Buss fishery had almost destroyed Scotland’s inshore ‘boat fishery’. Basing his arguments on the figures for 1771 – 1781, he ignores any effects from the fourth Anglo-Dutch War or from the American War of Independence, which disturbed Scotland’s trade with the West Indies and probably had more of an effect on the boat fishery.

But it seems the figures are dodgy anyway.

Accusing him of statistical manipulation, J Travis Jenkins points out that Smith places annual bounty inputs against the outputs of only the first voyage of each season – a herring buss would make two or three. The whole point of the buss fishery was its capacity to follow the herring from fishing grounds to fishing grounds and from May to January.

Smith chooses to ignore over 150 years of pamphlets making the economic case for a buss fishery.

As a backhanded compliment to his boat fishery advocacy, in 1786 the parliamentary committee looking into matters extended the bounty system to include the smaller inshore vessels.

Change

Between 1762 and 1796 Jenkins shows a doubling of the tonnage involved in the Scottish herring fishery and more than a tripling of the catch. Like any subsidy, the bounty system was open to fraud, but most herring writers see it as having provided one of the keys to the eventual establishment of England and particularly Scotland as top herring nations.

The C18th saw the square rig of the herring buss shift to the backward slanting rig of the lugger. In Sailing Drifters (1952) Edgar March points to the advantages of speed, lugger outsailing the boats of the Revenue Men. By the 1750s, he writes, it was a moot point whether many a fisherman on the South Coast was a smuggler in off moments, or a smuggler who went fishing in his spare time.

Along with the bounties, this may also have played a role in shifting opinion in favour of the larger boat, but it was the period of peace following the Napoleonic Wars that provided the context for the rapid growth of the British fisheries.

With the size of catches increasing – and perhaps with income diversification – the need for the bounty system declined and it was phased out completely by 1829.

The coming of the railways radically opened up inland markets for fresh fish. England and Scotland may never quite have shared Northern Europe’s enthusiasm for white herring, but the appearance of fresh challenged what there was. At the same time, rail enabled the development of milder smoked cures.

John Woodger of Seahouses in Northumberland invented the kipper in 1843, rapidly then establishing himself in North Shields, where transport links were better. In 1844, when trains came to Great Yarmouth, the bloater, a lightly cured version of red herring, met them on the platform.

The Rise of Scotland

Scotland came to be the dominant force in the UK’s fisheries. Well placed for efficient access to all the key herring grounds where the Dutch caught their premium herrings, it benefited from investment in harbours – often by expatriate Scots keen to alleviate the suffering created by the Highland clearances.

It drew huge advantage from its earlier challenge to Dutch dominance in the white herring trade. The Scotch Cure and the Crown Brand which guaranteed it became famous. It was actually the Dutch cure and the Scots were applying it with the same attention to detail.

By the end of the C19th, on its own it was catching more herring than the Dutch fleets had ever barrelled. Such was its success the 1880s brought a glut, temporarily depressing prices.

In the peak years before World War I the UK was selling 1,400,000,000 cured herrings to the Germans per year and only slightly less to the Russians. Scotland had roughly 60% of the trade.

Along with its fleet, for its expansion into the English fishing grounds from the 1870s, it brought its own curing workforce, in particular ‘the herring girls’. From the West of Scotland, the Hebrides, Shetland and Orkney, the North East of Scotland, some even from Ireland and the Isle of Man, they gutted, salted and barrelled the herring down the East Coast, working for the Scottish companies who set up curing stations in all the major herring ports.

IV: Collapse – The C20th and C21st

The Beginning of the End

The catches, the exports and the profits in the run up to World War I represent the high water mark of the British herring fishery. The sailing drifters were giving way to steam and the increased capacity it brought. Herring populations seemed to offer no limits to the advance of the Scotch Cure.

After the war, it was a different story. The disruptions it had brought were compounded by an economic blockade of the Soviet Union and the impacts of the Treaty of Versailles on the German economy.

British herring curers lost substantial sums to the catastrophic devaluations of the mark and some went out of business. Germany, which began building its own herring fleet before the war, was encouraged in a movement towards self-reliance by its lack of foreign currency.

The relative high cost of exported barrelled herring encouraged the ‘Klondyke’ trade, shipping fresh herrings to the picklers of Hamburg by steamer. This generated a fair bit of excitement, but masked the underlying problems.

When trade was possible with the Soviets, the curers found they drove far harder bargains than the Tsarist importers had done. And they played different national suppliers off against each other.

On Scotland’s West Coast, working in pairs the ring netters had pioneered trawling techniques, but in the North Sea, the British, by and large, stuck to drift netting. It was better at targeting adult fish and delivered a better quality product.

The technique of pelagic or purse seine trawling for herring was developed by the Americans, but was taken up enthusiastically by the Scandinavians, the Icelanders and other European fleets. It proved to be disastrous for the fish populations, but obscene catches deliver profits.

A Herring Board

The Herring Industry Board was set up in 1935 to arrest the decline in the British fishery. It regulated the industry, it offered loans, it encouraged the building of fishmeal plants and tried to encourage the home market for the refrigeration-enabled fresh herring trade with adverts and recipe books.

The British public – particularly the English, who seem never to have shaken off its associations with cheap food, poor quality control and papist fasting – resisted the encouragement to eat more herring. On top of this, even before World War II, herring populations began to show signs of decline.

The Factors of Collapse

Beam trawling had been introduced in the C19th, the nets held down by great wooden beams bumping along the sea bottom. There were investigations into the potential impacts, but people didn’t know enough about herring life cycles to recognise the importance of the gravel beds that were being damaged.

Purse seine trawlers were taking the juvenile herrings. The outlets provided by fish meal and fish oil factories meant that the natural disincentives produced by market gluts disappeared. And steam gave way to diesel and ever-greater catch capacities.

World War II gave the herring some respite. On top of naval commandeering of much of the fishing fleet, Operation Archery or the Måløy Raid in 1941 saw 570 British commandos destroy four Norwegian fish oil plants, the output of which was being used by the Germans in the manufacture of high explosives.

Unlike Operations Grouse, Freshman and Gunnerside, which ultimately destroyed a heavy water plant in Rjukan, the action didn’t get a film with Kirk Douglas, but the herring may have appreciated it.

After the war, things rapidly got worse. The British North Sea fishery began to move towards pelagic trawling in the 1950s, but that just added to the problem. Outside the Common Market, the import duty on British herring gave Dutch and Danish producers the advantage in the important German trade. Meanwhile, the tipping of fly ash from power stations was covering more of the spawning grounds.

The first experiments with the frozen fish finger were actually developed with herring, but it was cod which caught on and the great British public was seduced by the charm of its bland convenience.

The UK’s few fishmeal plants were closing, but encouraged by the Herring Industry Board, pet food plants were taking higher and higher proportions of the catch.

For many of the same reasons, Icelandic herring stocks dramatically collapsed in the 1960s. The collapse in the North Sea herring populations led to the British government initiating a total ban on all directed herring fisheries in its Exclusive Economic Zone in 1977.

A couple of Dutch boats were arrested by the Royal Navy, but the potential for a fifth Anglo-Dutch War was averted by the scientists who persuaded other herring fishing nations to join in with the ban, which lasted until 1983.

Whose Fish?

Costly increases in catching capacity has concentrated ownership of the bigger vessels. The European Community and then the European Union introduced quotas to address overfishing and in the UK they were, by and large, allocated to the large scale owners.

Some EU nations, such as France, protect smaller scale fishermen and their communities, not least because of the role this can play in developing sustainable fisheries.

In recent decades, however, the UK has shown little interest. Globalism and Adam Smith-inspired free market convictions in government and among a small number of very rich quota owners have created the situation in which, according to Greenpeace, around half of England’s quota is ultimately owned by Dutch, Icelandic or Spanish interests.

The overwhelming proportion of England’s herring quota was sold to a single Dutch company (and a single trawler, the Cornelis Vrolijk). It is landed in Ijmuiden in The Netherlands, which accounts for the herring having become such a rarity on English fishmongers’ slabs.

Scottish fishing quotas have largely remained in Scottish hands. The quota system almost reflects the situation prior to James I’s accession to the English throne: rights held by the rich; nationalism north of the border, laissez-faire to the south.

Scotland’s wealthy quota owners, however, have been committed to innovation. Their involvement in the £63m Black Fish Scam between 2002 and 2005 saw fish processing plants in Peterhead and Shetland secretly using underground pipes and secret weighing machines to land 170,000 tonnes of over-quota herring and mackerel.

Books

Salt and Fishery by John Collins, London, 1682

The Herring, its Natural History and National Importance by John M Mitchell, Edinburgh, 1864

The Herring and the Herring Fishery by JW de Caux, London, 1881

The History of the Dutch Sea Fisheries by A Beaujon, London, 1884

The Royal Fishery Companies of the Seventeenth Century by John R Elder, Glasgow, 1912

The Herring; its Effect on the History of Britain by Arthur Michael Samuel, London, 1918

The Herring and the Herring Fisheries by James Travis Jenkins, London, 1927

Sailing Drifters by Edgar J March, London, 1952

The Driftermen by David Butcher, Newton Abbot, 1979

Following the Fishing by David Butcher, Newton Abbot, 1987

The Sea Fisheries of Scotland by James R Coull, Edinburgh, 1996

The British Herring Industry: The Steam Drifter Years, 1900 – 1960 by Christopher Unsworth, Stroud, 2013

See also

- BATTLE OF THE HERRINGS (1429)

- BOHUSLÄN FISHERY

- BLACK HERRING

- BLOATER

- BUSS

- DIVINE PROVIDENCE

- DRIFT OR GILL NETTING

- DRIFTERS (DOCUMENTARY FILM)

- DUMAS ON HERRING

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- ENGLAND’S PATH TO WEALTH AND HONOUR

- EUPHEMISMS

- FASTING

- FIFIE

- FISH FINGERS

- GOLDEN HERRING

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- HERRING LASSES

- ICELANDIC FISHERY

- KIPPER

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- LOCKMAN’S VAST IMPORTANCE

- LUGGER

- MUIR, JIM (HERRING INTERVIEW, ACHILTIBUIE)

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- QUOTAS

- RACIAL THEORY

- RECIPES FROM THE HERRING BOARD

- RED HERRING

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- RING NET: WILL MACLEAN

- RING NETTING

- SALT

- SILVER HERRING

- SMITH, ADAM: WEALTH OF NATIONS

- SUFFERING SALTWORKERS OF SHIELDS

- PURSE SEINING

- SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS

- SWIFT, JONATHAN

- ULLAPOOL

- WHITE HERRING

- WITCHCRAFT

- YAWL

- ZULU