An 8,000 year history of salt and salt pickling, paying particular attention to the preservation of herrings by the German Hanse, the Dutch and the British.

SALT

A kiss without a beard is like an egg without salt, my sister used to tell me. It is an act of betrayal to eat an egg saltless, anyway. And the last time I shaved off my beard (1988) I was threatened with divorce. It is hard to overestimate the importance of salt.

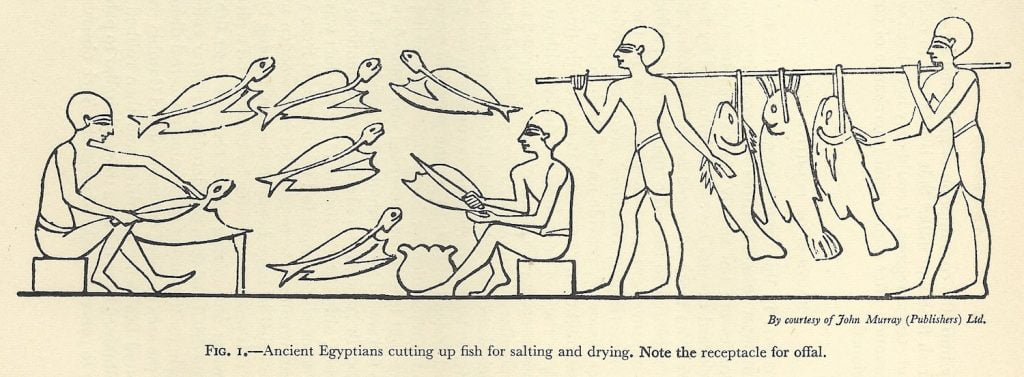

The earliest salt harvesting – simultaneously in Romania and at a salt lake near Yuncheng, some 500 miles south west of Beijing – seems to have been around 6,000 BC. There was salt pickled fish in China around 2,000 BC. The Ancient Egyptians had also developed a taste for it by this time – there are pictures in tombs. It has been suggested, however, the art originated with the Harappan civilization in the Indus Valley, some 400 years earlier.

I like to think of the Harappans enjoying a bit of Bombay duck from just down the road at Arnala on the Maharashtran coast, where I once spent an idyllic week. As to whether they invented the salt pickling of fish I confess to having doubts. It’s hard to imagine a salt harvesting industry that took 3,600 years to discover you could do more with it than sprinkle it on your chips.

It’s been said – don’t ask, I can’t remember where – more of this country’s forests were cut down producing salt than ships. Having cleared most of Norfolk’s trees, the Broads were dug out for peat between the C12th and C14th. The proximity of Yarmouth places herring salting at the heart of demand.

Preserving Herrings

The herring is an oily fish, which makes it harder to dry, but the oil contains several polyunsaturated fatty acids – including the health food-beloved Omega-3 ones, DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic). Sadly, unsaturated oils are also good at combining with atmospheric oxygen: herrings go off quickly.

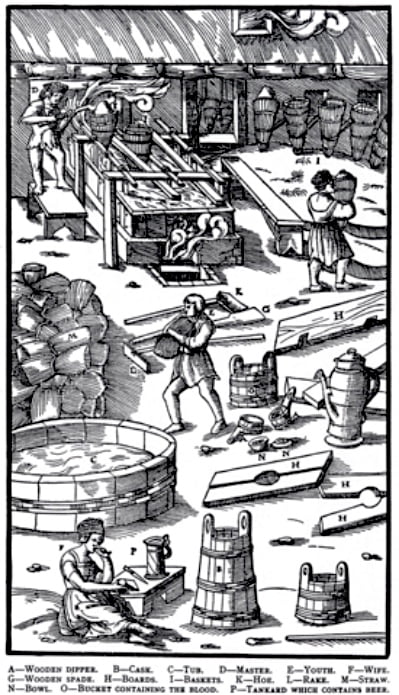

Pickling in salt, minimises oxidation. Salt draws water from the fish by osmosis and in brine concentrations of around 20% kills off most dangerous bacteria. Tightly barrelling the brined herring further minimises the access of oxygen. This gives you a product, white herring, with an extensive shelf-life. Shelf-life is marketability. The scale of herring catches, combined with shelf-life, insisted on the development of trade. This simple fact lies at the heart of most of the herripedia’s entries.

Smoking delivers tarry phenols, which also have antioxidant properties. Salt (dry or brine) and smoke is another one of those marriages made in Heaven. Highly salted and highly smoked red herrings have similar shelf-lives to white herring. Reds were barrelled up dry, but were less dependent on it for their longevity.

The preservative qualities with both white and red herring were reliable enough for them to become an effective currency in the Middle Ages, the barrels of red breaking down into convenient units of small change.

Lightly salted and smoked cures, such as the kipper and the Yarmouth bloater, were inventions of the railway age, which also enabled the development of the fresh fish trade.

The Quality of Salt

Some people are pickier than others – it is to them we should be grateful for the advances in salt and salting. As communities and nations competed for trade opportunities – and Catholic fasting tradition’s quasi-insistence on fish eating on Fridays and during Lent created huge opportunities – the quality of the salt became ever more important, especially with white herring.

Purity was a factor. Salt whether from the sea or from brine pits was evaporated, either by the sun or by fire. Sand, silt and soot all presented problems. A further problem was what is known as bittern. With salt, it’s sodium chloride you’re after. Evaporating seawater or the water from brine pits, you get lots of sodium chloride, but you also get calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, sulphates, bromides, iodides and more. In salt manufacture, these are called bitterns and they give a bitter flavour.

Essentially there’s sea salt and there’s rock salt, but there are different processes.

Sea Salt

A salt marsh will see crystals forming by natural evaporation. It won’t have taken much for the recognition of this to inform industrial development. As John Collins says in Salt and Fishery (1682), Where the Sun shines hot, and the Tides vary but little, tis easie to have Salt enough. In Europe, however, the Atlantic herring only swims as far south as the Bay of Biscay.

A number of herring populations favour the Baltic, even adapting to the low salinity of its eastern and northern waters with the variant Clupea harengus n membras or Baltic herring. But getting salt out of low saline seas is hard work. Two things come from this: trade and engineering innovation.

Where there is a significant tidal difference, salt producers can work with this, taking seawater at high tide – spring tides by preference – and channeling it into shallow holding pools or salt pans. The less silt and sand you take in the better, but the holding pools allow both to settle to the bottom.

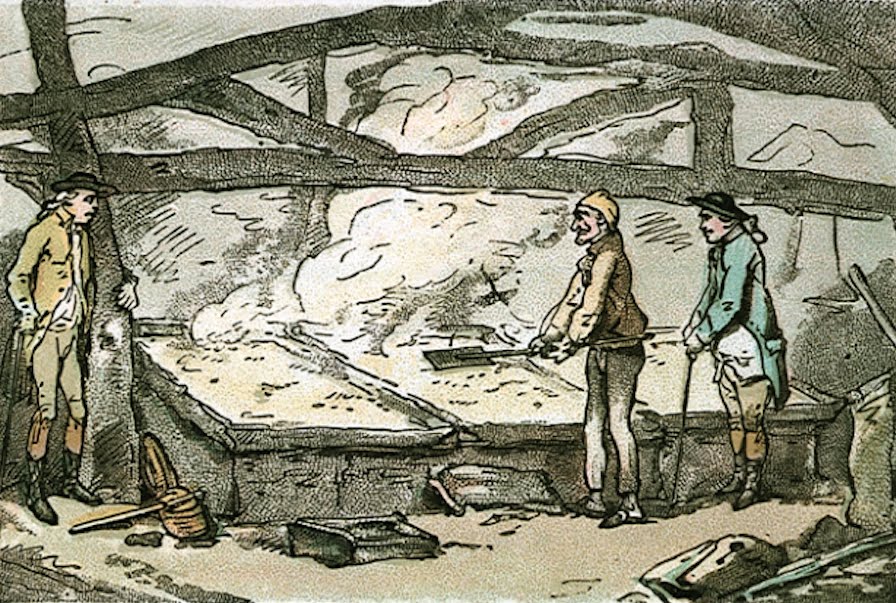

There can be a series of ponds, taking advantage of the sun or not, depending on its general availability. In northern climes, the brine is channeled into metal salt pans. Originally lead, then wrought iron, these days stainless steel, the salt pan allows evaporation by wood, peat, coal or gas fires.

John Collins goes into detail on traditional English sea salt making, focusing on the two main production centres in his day, Lymington in Hampshire, where both sunshine and coal were used, and South Shields on the Tyne, where, understandably, they just used coal.

The want of Brine-Springs on the Eastern Coasts of England, begat the necessity of making much salt at sheilds, and in the Counties of Durham, and Northumberland.

The Pans there used are made of wrought Iron, of 18 or 19 foot long, 12 foot broad, and 14 inches deep; the Fewel being for the most part, a sort of crusty, drossy, mouldring Coal, taken from the upper part of the Mine, which if not spent this way, would be for little or no other use, to the prejudice of the Coal Miners, and be mingled with the better sort of Coals, to the great dammage of the Buyers, especially those of London.

The Sea-water they commonly at Spring-Tide let into Ponds called Sumps, from whence ’tis pumpt into their Pans, which are six or seven times filled, and half or more every time Boyled away, before it becomes Salt.

Bay Salt: Technically this is the term for the sea salt, sun-evaporated in the Bay of Bourgneuf, near Nantes, particularly Guérande and Noirmoutier. It was the closest traditional sun-evaporated salt production to the major herring grounds and the term came to describe any salt produced in this way – in Spain, Portugal or the Mediterranean and, as Europe’s colonial expansion grew, in Cape Verde and the Caribbean. The Dutch, however, leading the charge on quality, used the term specifically to ban the use of salt from Bourgneuf, because of its high clay content.

Jerbo Salt:

At Jerbo, a place n Barbary, 30 Leagues to the Westward of Tripoly, is much Salt made, on a plain of red Sand, by the Sun’s vigour: the Sea (which ebbs and flows but about a foot,) making its way through the Sea sandy-Banks into the Plain aforesaid. A Bassa seeing a Ship Arrive from Sea, and Anchoring on the shoales where is safe Riding, estimates her Bulk, and sells her Lading for about two Dollers a Ton, the which is carried on Board by Turks, or Moors into the bargain.

This Salt is of so strong a Grain, that it will not readily Dissolve in fresh-water, wherefore if it be necessary the Marriners put fresh water to it, to wash out the Dirt and Sand, powring away the Liquor that will run.

Salt and Fishery, John Collins (1682)

Moor Salt: The Dutch produced this by soaking and evaporating the ashes from burning salt-rich estuarial turf. It was purer than Bay Salt, but fairly soon they found they didn’t have enough estuarial turf to cope with demand.

Fleur de Sel: Flower of Salt in English, Flor de Sal in Spanish Portuguese and Catalan, this is the artisan-gathered crust of salt crystals that forms on the surface of evaporating seawater. Collected since Roman times it has always played to the top end of the gourmet market and mostly hasn’t been used for salting herrings.

Given England’s historically lamentable reputation for salt, it’s interesting, however, that Maldon Sea Salt – a firm established in 1882 – has developed an international reputation out of its salt crystal production. Many of the Essex salt producers at the time were coal merchants, making salt on the side. Maldon developed a carefully controlled version of metal salt pan production, these days using gas. It’s a splendid product.

Rock Salt

Of Salt made of the Brine from Pits

One of the most Ancient ways to make Salt, is by boyling of Bryne from Springs or Pits; whereof the most Eminent are found Cheshire, and Worcestershire, of which in Order.

The Cheif in Cheshire are at Northwich, Middlewich, Namptwich, of which those at Northwich have the perheminence.

Salt and Fishery, John Collins (1682)

The brine combines fresh water with rock salt deposits – either salt domes or salt beds. -Wich is a common place-name suffix for salt producing towns and villages in Cheshire and Worcestershire. It may derive separately to the Scandinavian -wicks and -wiches (simply towns) of Eastern England. Collins provides an account of production at Droitwich:

There are many Salt-Springs, particularly one in the great Pit at Upwich, of which is made 450 Bushels of Salt in every 24 hours, so strong that 4 Tuns of Brine make one Tun of Salt.

The Brine is said to be so strong, that it cannot be Boyled in Iron-Pans, neither Cast nor Wrought, because the former breaks, and the latter is too soon Corroded…

They say they are therefore driven to the use of Leaden-Pans, 5 foot and a half long, and 3 foot wide, whereof the sides and ends are beaten up.

Their Fuel was formerly all Wood, but since the Ironworks in the Forrest of Dean have destroyed the Wood there, etc. they cannot at any resonable distance be supplied for one quarter of a Year, and are now forces to use Pit Coles, that are brought 13 or 14 miles.

Collins is a great advocate of the quality of Cheshire’s and Worcestershire’s rock salt. The problem it had in his time was that it was on the wrong side of the country for the major herring fisheries and land transport was expensive.

Rock salt has been mined at Hallstatt in Austria since 5,000 BC, but it wasn’t until the C17th that the deposits in Cheshire began to be directly mined. With the development of the railways in the C19th, transport economics shifted in favour of the UK’s rock salt and this took over from sea salt as the prime herring curing product.

These days, the making of most salt in this country is achieved by forcing water down a borehole into underground salt domes and salt beds. This creates what is known as solution-mined brine. The water is then vacuum evaporated (more reliable than sunshine in the UK), centrifuge-dried and then, for table salt, finished off by drier-coolers.

Salt on Salt

Of Salt upon Salt, or Salt made by Refining of Forreign Salt

The Dutch above 50 years since finding the ill qualities and effects of French Salt, both as to Fishery uses, and for curing of Flesh for long Voyages, besides the discolouring of Butter and Cheese, Prohibited the use thereof by Law, and being at Wars with Spain, Traded to Portugal, St Tubas, and the Isle of May, for Salt granulated or kerned meerly by the heat or vigour of the Sun, and fell to the refining thereof at home by Boyling it up with Sea-water, and thereby cleansing it of the three ill Qualities, to wit, Dirt, Sand and Bittern.

In the UK the refining of Salt on Salt was also achieved by adding rock salt brine.

Size of Grain

Collins was on a mission to encourage the English salt industry – both sea and rock. He rarely misses an opportunity to point out how Portsea Salt from Lymington or Cheshire’s rock salt might, with advantage, replace fishery dependence on Bay Salt. Salt shortages, due to wars with Spain and France in the C16th and C17th had led to petitioned encouragement of native salt making, which Charles I, a herring industry enthusiast like all the Stuarts, happily granted in 1630.

CL Cutting in Fish Saving: A History of Fish Processing from Ancient to Modern Times (1955) points to the disincentives. Apart from the reputation for impurity, which was obviously even worse than that of Bay Salt, fire-dried salt was produced too quickly. This affected the size of the grains. It delivered a smaller kerned salt (from kernel and from which corned beef).

Large grained salt obtained by slow crystallisation was preferred to finer salt. The reason for this is now believed to be that fine salt rapidly coagulates the surface tissues, preventing further penetration of salt into the flesh, giving rise to a condition known to the trade as ‘salt burn’.

Salt Use of the Great Historical Herring Fisheries

Skåne: In the context of the huge C12th to C15th shoals off the Skåne coast of southern Sweden, it was Lüneberg’s rock salt that enabled the German Hanse to lever control of the international herring trade developed by the Danes. The Dutch, English, Scottish, Norwegian and other fishermen who flocked to the miraculous fishery were not allowed to cure or even keep their own catches. They were only allowed to sell them to the Hanseatic curing stations on shore.

By the late C14th, the Dutch were shipping Bay Salt to the Baltic and the Skåne fishery. It probably became competitive because of the cost of land transport.

The Dutch: Long before the dawn of the Dutch Republic, as far back as the C7th Dutch fishermen were exploiting the herring off the English coast. They will have helped to shape the Yarmouth Herring Fair, which ran from Michaelmas (20th September) to Martinmas (11th November). There were several salt pans in the area and, curing on the shore, they were most likely to have used local salt. On the way over, they will have been keen to fill their holds with goods they could sell at the fair.

The development of the Dutch herring buss in the C15th increased the hold capacity. Dutch curing regulations increasingly insisted on better quality salt and salting at sea. An additional incentive to staying offshore was avoidance of licence payments in waters they also avoided recognising as English or Scottish.

Initially, they used Bourgneuf Bay Salt, in which they were already trading, shifted to Moor Salt, then Portuguese Lisboa and Salt on Salt. They managed to maintain access to Portuguese and Spanish salt even when they were locked in war with Spain.

The British: The salt production industry is the most fully recorded in The Domesday Book of 1086, both sea and rock salt. Records of Scottish sea salt pans go back to the C12th, when Prestonpans was given a royal warrant – it continued production through until 1959.

By the C17th English production was focused on Lymington’s Portsea Salt (named after Portsea Island at Portsmouth, from which it was shipped); the rock salt of North-, Nant-, Droit- and the other -wiches of Cheshire and Worcestershire; the coal-dried sea salt of the River Tyne, notably at South Shields.

Scottish production, which had moved similarly to the use of coal, was mostly based on the Forth, with pans at Culross, St Monans, Joppa and elsewhere. During the Siege of Newcastle in 1644, the Scottish Army of the Solemn League and Covenant, took the opportunity (while helping out English Parliamentary forces) to systematically destroy the salt pans and boiling houses of the Tyne, eliminating the competition.

Benefitting from lower and less rigorous salt taxes, from the C17th the Scots flooded the English market with smuggled salt, but the English continued to import Bay Salt. Scottish salt production largely collapsed after the duty on salt was abolished in 1825.

In one of the frequent oversights of colonialism, the British continued to impose the salt tax in India for well over 100 more years. Gandhi’s Salt March of 1930 was one of the key protests leading to Indian independence.

Lymington continued producing salt until 1865, but was ultimately disadvantaged by the cost of coal on the South Coast. Collins details the complaints of Tyneside’s salt makers – Scottish depredations, Scottish smuggling, unfair English taxes administered by over-greedy tax farmers, the land rentals charged by the Church at Durham. There’s no getting round the fact, however, that the salt they made had a bad reputation and production declined over the C18th.

Maybe using the most of its bitterns, the combination of salt and coal on Tyneside contributed to the growth of a chemical industry. This moved to Teesside in the C19th, helped by the discovery there of a rock salt deposit.

With technological improvements to the process enabling variety in grain size, it was the -wiches which won out in British salt production and supply, Maldon as a late runner, coming in to capture the quality end of the market.

NOTE: A link to the Hathi Trust’s freely available PDF of John Collins’ Salt and Fishery is provided below. Due to sloppy typesetting in 1682 it looks like pages 33 to 48 are missing, but they’re not. It is just a page numbering error.

See also

- BALTIC HERRING

- BATTLE OF THE HERRINGS (1429)

- BEUCKEL, Willem

- BLACK HERRING

- BLOATER

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BUCKLING

- BUSS

- DRIED HERRING

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- FASTING

- GERMAN SPIES

- GOLDEN HERRING

- HARENG SAUR

- HERRING LASSES

- HERRING UNDER A FUR COAT

- ICELANDIC FISHERY

- JANSSON’S TEMPTATION

- JEWISH RECIPES

- KIPPER

- KLONDYKING

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- PICKELHERING

- RED HERRING

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- ROLLMOPS & BISMARCKS

- SCHMALTZ HERRING

- SILVER HERRING

- SUFFERING SALTWORKERS OF SHIELDS

- SURSTRÖMMING

- VENTJAGER

- WHITE HERRING

- WHEN HERRINGS LIVED ON DRY LAND