Charles I, The Stuarts, Maritime sovereignty, the herring and the building of a flagship

SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS

Maritime sovereignty was not always a top obsession with the world’s powers and potentates. Enforcement demanded the expense of a standing navy and the greater the coastline, the greater that expense. Scotland has a huge coastline and had very little money, but was, nevertheless an early adopter of the territorial waters obsession.

The Netherlands, at half its size, had grown fabulously wealthy and as salt in the wound put its economic miracle down to the herring shoals God provided specifically for them just off the The Shetlands and coasts of Scotland and England. With James VI of Scotland’s coronation as James I of England, the Stuarts brought their herring shoal obsessions with them. In 1634, James’ son Charles I commissioned the building of a flagship to be called Sovereign of the Seas.

Early approaches to enforcement

Historically, kings had been able to dispense with large standing navies: most imports required ports, where goods could be easily taxed; should strangers wish to fish in what a king considered his waters, they could pay a fee and the nation would be told, These are our friends; if a stranger chose not to be a friend, a king could rely on the natural xenophobia of his own fishermen. Fish had to be cured, nets had to be dried and mended, provisions had to be purchased, vast quantities of beer had to be drunk. Money was made and there was always the danger that this would trump xenophobia, but the key fact was that the strangers had to come ashore.

A land’s kenning

When it came to maritime sovereignty, in the C17th the Dutch were advocates of what later became known as the cannon shot rule – the distance at which a shore-based cannon stood a reasonably reliable chance of hitting a stranger’s vessel (or vice versa). In the early C17th this was only about a mile and was obviously nowhere near good enough for the Stuarts. They favoured a land’s kenning: 14 landlubber’s miles or 12 nautical ones. This was deemed to be the furthest from which, at the top of a mast on a fair day, a seafarer could see the shore.

Standing in an open fishing boat with your eye 5 feet above sea level your horizon is only going to be 2.738 miles away. The mast would need to be 105 feet tall for your crow’s nest lookout to make out the horizon at 12 nautical miles. A boat would need a keel length of between 78 and 84 feet to support that mast. Only the very largest medieval cogs would have been able to ken 12 nauticals. With cliffs or coastal hills, you could achieve some fairly satisfactory kenning, but good luck with East Anglia and Lincolnshire.

There are tables which can be used to make the necessary calculations, but by the time you’ve put refraction, visibility degradation, weather and atmospherics into the equation, you’re going to be lucky if you can see more than 14 miles however tall your mast.

Lookouts were employed, but the idea of a precise land kenning from the top of a mast has the slight whiff of mathematically post-rationalised tavern talk about where a sailor might have been when he once saw Flamborough Head. With a 127′ keel, however, Sovereign of the Seas would be well-equipped to establish Britain’s territorial waters. In the event of an argument, it was also going to have more guns than any ship in the Dutch navy.

The cannon shot rule was formalised in the early C18th and later became the 3 mile limit as accurate ballistic ranges improved. Even the British eventually accepted it, although possibly because, by the late C18th, they were more concerned with the coastlines of others. By that time Sovereign of the Seas was long gone.

The problem with the Dutch

In the early C15th the Dutch developed Die Groote Visserye, its grand herring fishery. It was based aroundits herring buss fleet: hundreds of large factory ships, gutting, salting and barreling at sea. Generally around 50′ long, the Dutch had developed the buss so they could exploit the herring shoals of Shetland, Orkney, Scotland’s east and west coasts and the eastern and southern coasts of England. What people thought of, at the time, as a grand migration of herrings was, in fact, a number of sequentially appearing populations. With their busses, the Dutch were able to fish for herring eight months a year, for the most part working their way north to south. They obviously could come ashore, but they didn’t need to.

They initially seem to have paid for licenses. James III of Scotland, who’d woken up to his nation’s herring potential when he acquired Shetland and the Hebrides as part of the dowry for marrying the 13 year old Margaret of Denmark, only seems to have wanted to emulate the Dutch with Scotland’s own fleet of busses. As Die Groote Vissereye grew, however, the Dutch fishermen were having to pay, at home, for an often inadequate naval support. They were also often forces to pay protection money to the Dunkirk privateers and other pirates – unfortunately, barreling at sea created an attractively tradable booty. Scottish and English demands may have slipped down the list of their priorities.

England had been comparatively relaxed about the Dutch busses. For most of the C16th The Netherlands was still part of the Holy Roman Empire. Henry VIII blew hot and cold with Emperor Charles V, but in one of his warmer phases he may even have granted Dutch herring fishers free access to English waters. The Dutch later claimed he had, anyway. When the Dutch Revolt kicked off in the 1560s, a new Protestant nation emerged. Even more convinced of its God-given herring shoal-funded destiny, it seems to have shown less and less concern for English and Scottish sensibilities. Elizabeth I, however, was more interested in its potential as an ally against Catholic Spain and France.

Things changed with James Stuart’s succession to the throne. On its own Scotland had not had the heft to deal either with the Holy Roman Empire or the Dutch. In 1532, his grandfather had declared a war on The Netherlands, which lasted 9 years. What some have called his navy, some have described as his own licensed privateers. Either way, they seized a few busses, but probably not as many as other pirates seized as a matter of course and at the cost of reciprocal losses. There was eventually an agreement with Charles V, but it didn’t seem to have much effect. Then as now, fishermen at sea can show an opportunistic disregard for regulations and instructions.

James saw his new ‘united’ kingdom as heft at last.

Jurisprudence

The Dutch played a long game. James shouted at their ambassadors, but the English navy was itself quite heftless. Quite apart from its Dutch counterparts, it could be counted in tens, while the Dutch busses were counted in hundreds.

A cat was thrown among the pigeons, when the Dutch commissioned one of their top jurists Hugo Grotius to write and publish Mare Liberum (the free sea, 1609). Technically it had nothing to do with herrings. The Portuguese had complained about a Dutch East Indiaman seizing one of their vessels in what they considered Portuguese East Indian waters.

European colonialism saw a growing interest in maritime sovereignty. The Spaniards considered the whole of the Pacific closed to the other powers. Grotius, however, challenged the very concept of ‘Portuguese’ waters in the East Indies. The sea, he said, was more like the air than it was like the land:

The air belongs to this class of things for two reasons. First it is not susceptible of occupation; and second its common use is destined for all men. For the same reasons the sea is common to all, because it is so limitless that it cannot become a possession of any one, and because it is adapted for the use of all, whether we consider it from the point of view of navigation or of fisheries.

Grotius later claimed he’d only been talking about the freedom to seize other nations’ ships on the high seas, but, of course, his high seas started a mere mile offshore. James understandably read it as an attack on his herring rights. He commissioned top English jurist John Selden to write a counterblast, Mare Clausum (the closed sea).

An obvious person to have asked would have been Scottish jurist William Welwod, who’d written the first book on maritime law, The sea-law of Scotland (1590). With an admirable commitment to accessibility he’d even written it in Scots. Welwod wrote a reponse to Grotius, anyway, updating and expanding his earlier work with An Abridgement of All Sea-Laws (1613). From a fishing perspective, his arguments are by far the most interesting:

If the uses of the Seas may bee in any respect forbidden and stayed, it should be chiefly for the fishing, as by which the fishes may be said to bee exhaust and wasted; which, daily experience these twenty yeares past and more, hath declared to be ever true: for whereas aforetime the white fishes daily abounded even into all the shoares on the Easterne coast of Scotland; now forsooth by the neere and daily approaching of the busse Fishers the sholes of fishes are broken, and so farre scattered away from our shores and coasts, that no fish now can be found worthy of any paines and travels; to the impoverishing of all the sort of our home-fishers, and to the great damage of all the Nation.

It still resonates: maritime sovereignty should first and foremost protect the livelihoods of those who fish from a sovereign’s coastline. Maybe, in a vision, James foresaw a nation that would one day need to shaft its fishermen as a trade off against the greater needs of its financial services sector. It’s worth taking time, however, to imagine Welwod’s principle written into our understanding of maritime sovereignty.

Selden had more of an instinct for the kind of thing James wanted. He dug up the historical precedent of England’s Edgar I, who had claimed to be King of the Seas. Edgar may only have been claiming lordship over various islands, but words is words. Selden also claimed the King Canute Precedent. Sitting on his throne on the beach, Canute legendarily addressed the waves:

Thou, O sea, art under my dominion, like the land on which I sit; nor is there anyone who dares resist my commands. I therefore enjoin thee not to come upon my land, nor to presume to wet the feet or garments of thy lord.

Selden’s argument puts to one side Canute’s intention – to demonstrate in all humility the limits to earthly power. Canute had necessarily asserted sovereignty, in order for the seas to ignore him.

James liked it, but he was a cautious man and chose not to aggravate a difficult situation with an inadequate navy. He also chose not to put the public purse to the expense of preventing its continued deterioration. He didn’t publish Mare Clausum.

Enter King Charles

The fleet stood at a mere 30 ships in 1625, when Charles Iwas crowned King of England, Scotland, Ireland and France. The coronation organising committee had obviously chosen to ignore the fact that Calais, the last bit of English France, had been lost back in 1558, but it probably wouldn’t have made any difference. Charles was not a cautious man.

To be fair, the Dutch navy and the Dunkirk privateers were thinking nothing of continuing their sea battles without regard to proximity, even chasing each other into English ports and marching across English soil, if necessary.

Forget about the 14 miles the Dutch didn’t respect anyway, not only was his bit of the Mare claus-ed, but, even without an inch of its land, as King of France he laid claim to its land’s kenning-worth of sea. His navy would ensure the peaceable traffic through the English Channel of all nations’ merchantmen. As long as they lowered their flags respectfully on approaching any of his ships, he generously offered neither to seize nor sink them.

Crafty Cardinal Richelieu (yes, he) simply told the French navy not to raise its flags in the first place. This kind of cleverness was frustrating for Charles, but he was a big picture man.

Within his claimed waters, he had a vision of a single, united British fishery catching all his herrings. It would be just like the Dutch one, except all that wealth, which had enabled their rise to greatness, would be his. It would be An Association for the Fishing, a joint stock company as part of which English adventurers could fish in Scottish waters, Scottish in English and everybody else would have to pay. He wrote to the Scottish parliament:

This is a worke of so great good to both my kingdomes that I have thought good by these few lynes of my owne hand seriouslie to recommend it unto yow. The furthering or hindering of whiche will ather oblige me or disoblige me more then anie one business that hes happened in my tyme.

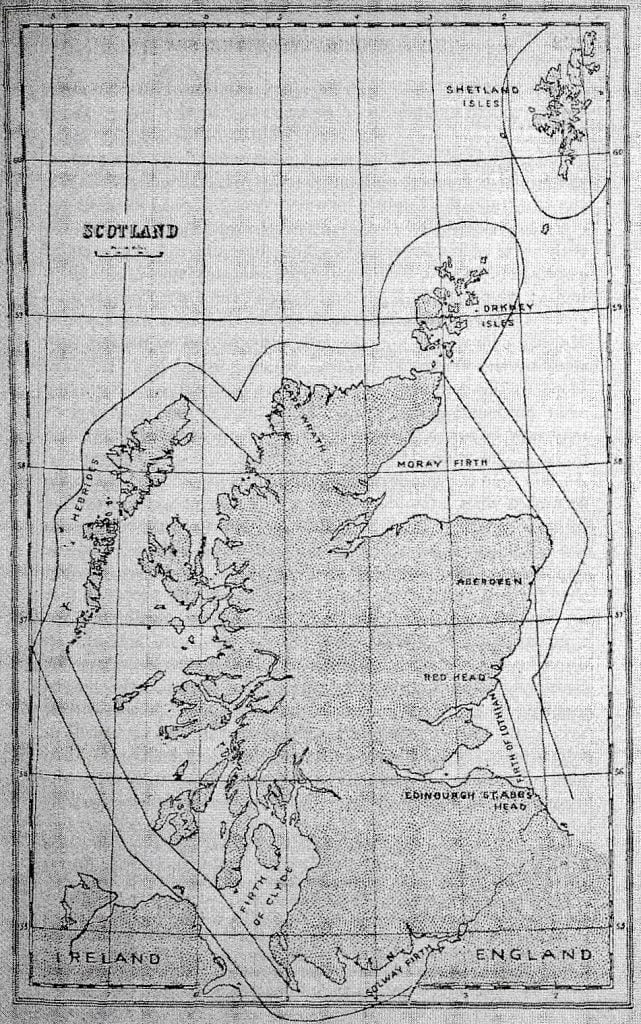

The Scots, possibly following Welwod, went as far as expressing rare concern for the livelihoods of their fishermen and helpfully drew a map of the waters they would like to reserve for Scottish boats: all the firths, together with The Minch and then a further land’s kenning on top of that, plus 14 miles out from the other side of the Outer Hebrides, The Orkneys and around The Shetlands.

The English were welcome to Fair Isle.

As long as they kept outside these lines and if Charles would also rid them of the Hollanders, they would, of course be more than happy to discuss his ‘British’ fishery. Charles pulled the kind of rank only Divine Right gives you and there were compromises, but, when it came to it, neither the English nor the Scots invested in anywhere remotely near the 200 British Busses of Charles’ plans.

Sadly, such English adventurers as there were proved incompetent fishermen. Given time, maybe they could have learnt, but, of the handful of busses built or bought, most were seized by the Dutch or by the Dunkirk privateers.

Build me a navy

Charles ordered a shipbuilding programme, which would include Sovereign of the Seas. It was Selden writ large. The flagship was built by Peter Pett, drawing on the advice of his father, Phineas, the Royal Shipwright. With texts and narratives suggested by the poet and playwright Thomas Heywood, its extensive decorative carving and its mottos were executed by John and Mathias Christmas. Heywood wrote an account of its construction:

What Artist tooke in hand this ship to frame?

Or Who can guesse from whence these tall Okes came?

Unlesse from the ful grown Dodonean grove,

A Wildernesse sole sacred unto Jove.

What Eye such brave Materials hath beheld?

r by what Axes were these Timbers feld?

The artist was actually Charles’ Flemish court painter, Anthony van Dyke, working hand in hand with Heywood himself, who was also a theatrical designer. Meanwhile, far from some Dodonean grove, the oaks mostly came from Chopwell Wood, south west of Newcastle upon Tyne and next to which I happen to live. Let me tell you, it hasn’t ever recovered from the loss of every single one of its mature and healthy oaks. This may have coloured my thinking on the Stuarts.

With the timber still seasoning, in 1635 Charles at last published Selden’s Mare Clausum. He knew Sovereign of the Seas was going to be a corker. It was to be decked out in just black and gold (the gilding alone came to £6,691). Its 102 canons cost £26,442, each one inscribed at an extra £3 a pop with Carolus Edgari sceptrum stabilivit aquarum (Charles established Edgar’s sceptre of the waters). Twelve of the canons were later removed because they affected the ship’s stability, but never mind, King Edgar himself rode its beak-head on a horse, trampling the heads of the seven kings of the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy. It was sea-borne propaganda on the grand scale.

Translating a Latin original by prodigy of the age Henry Jacob, Thomas Cary wrote:

Triton’s auspicious Sound usher Thy raigne

O’re the curl’d billows, Royal SOVERAINE,

Monarchal ship, whose Fabrick doth outpride

The Pharos, Collosse, Memphique Pyramide:

And seemes a moouing Towre, when sprightly gales

Quicken the motion and embreath the sailes.

We yt have heard of SEAVEN now see yt EIGHT

Wonder at home; of Naval art the height:

This Britain ARGO putts down that Greece,

Be-Deck’d with more then one rich Golden Fleece,

Wrought into Sculptures which Emblematize

Pregnant conceipt to the more curious eyes.

eptune is proud o’th burden, and doth wonder

To hear a Fourefold fire out-rore Ioue’s Thunder:

Onn then, Triumphal Arke, with EDGAR’s fame,

To CHARLES his Scepter add ye Trident’s claime.

Some have suggested Cary to be a variant spelling of the Cavalier poet Carew, but Thomas Carew was actually quite good.

The total cost of Sovereign of the Seas was £65,586, which was a lot. Nobody minds a king’s profligacy with his own money, but the standard English way of funding naval building was Ship Money, an occasional tax levied on coastal towns for the protection offered their fishermen, merchants and harbour investments. Having a flagship was, of course, predicated on a significantly expanded fleet with each of its ships requiring its own construction budget. Charles decided to extend Ship Money to his inland towns. Just as the whole Dutch nation had, these would all benefit from the vast accrual of herring fishery profits and come to appreciate the need for increased taxation.

Heywood wrote, optimistically:

Seeing his Majesty is at this infinite charge, both for the honour of this Nation, and the security of his Kingdome, it should bee a great spur and incouragement to all his faithful and loving Subjects to bee liberall and willing Contributaries towards the Ship-money.

It wasn’t and they weren’t. A number of humiliations were inflicted on Charles’ expanding navy, particularly in the English Channel. Dutch, French, Dunkirkers and Spaniards: nobody seemed to be quaking. The presence of a Spanish fleet in English waters was not entirely unplanned. Charles had signed a secret treaty with Spain as an ally against the Dutch and the French. Politically, however, he couldn’t tell the British people, They are our friends. He was suspected of being a closet Catholic, anyway.

With Sovereign of the Seas still being built, Charles sent ships north under the Earl of Northumberland and a number of the Dutch fishermen paid for licences. The amount paid, set against the costs of the expedition, was glossed over, but the following season, defending its fishermen, the Dutch navy came north in numbers. The English tactical retreat seemed of a piece with its other humiliations.

England’s taxpayers were not happy. The extension, scale and imposition of Ship Money became one of the key grievances leading to the English Civil War. Charles lay his head on an oak block before Sovereign of the Seas had even seen action.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars

The logic that had led to Charles’ ambitious naval expansion remained. Oliver Cromwell may not have shared the Stuart obsession with herring, but a promise of wealth and empire is a promise of wealth and empire. Perhaps by then an Anglo Dutch War had become inevitable, but it was Cromwell who kicked it off.

It wasn’t until The Battle of the Kentish Knock that Sovereign of the Seas saw action. She’d briefly been renamed The Commonwealth, then just The Sovereign, but the Dutch were genuinely impressed. They called her Den Gulden Duvel, the Golden Devil.

The First Anglo-Dutch War (1652 – 54) ended up more-or-less as a stand-off. Even though he renamed his flagship Royal Sovereign,Charles II was defeated in the Second (1665 – 67) and in the Third (1672 – 74). The ship that had been Sovereign of the Seas was accidentally burnt down to the waterline in 1696. Herrings weren’t involved in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1781 – 84). Herrings weren’t even a casus belli in that one.

Anglo-Dutch Wars 1 – 3 had a damaging effect on Dutch herring fishing and some attribute to them the collapse of Die Groote Visserye. With approximately 1,500 busses in the 1630s, by the end of the C17th it had been reduced to 500.The secret in herring fishing conflicts seemed simply to have been keeping your opponents’ vessels tied up in their home ports for as many seasons as possible.

The French, though, may also have played a significant role. In 1703, in a little-mentioned action of the War of the Spanish Succession, six French men-of-war sank a Dutch warship off Fair Isle. Its three companions on fishery protection duties scooting off, the French proceeded to Bressay Sound in the Shetlands where they set fire to 400 Dutch busses, generously allowing the fishermen all to sail home in those that remained.

In 1734, Jonathan Swift was still, enraged at the folly of England, in suffering the Dutch to have almost the whole advantage of our fishery, just under our noses. In 1772, however, as part of another conflict, the French navy went back to Bressay Sound and delivered the coup de grâce, burning another 150 herring busses.

Everything took place within a land’s kenning and in 1703 the Dutch had been British allies. The incidents could have been seen as humiliations, but, treaties notwithstanding, British distress may have been tempered with an every cloud has a silver lining. It still took Britain’s fishermen and curers more than a hundred years before they began to dominate the herring trade. That, however, is another story.

A True Discription of his Majesties royall and most stately ship called Soveraign of the Seas, Thomas Heywood (1637) – complete text

I began at the Beak-head, where I desire you to take notice, that upon the stemme-head there is Cupid, or a child resembling him, bestriding, and bridling a Lyon, which importeth, that sufferance may curbe Insolence, and Innocence restraine violence; which alludeth to the great mercy of the King, whose Type is a proper Embleme of that great Majesty, whose Mercy is above all his Workes.

On the Bulk-head right forward, stand six severall Statues in sundry postures, their Figures representing Consilium, that is, Counsell: Cura, that is, Care: Conamen, or industry, and unanimous indeavour in one compartment: Counsell holding in her hand a closed or folded Scrole; Care a Sea-compasse; Conamen, or Industry, a Lint-stock fired. Upon the other, to correspond with the former, Vis, or Vertue, a sphearicall Globe: and Victoria, or Victory, a wreath of Lawrell. The Moral is, that in all high Enterprizes there ought to be first Counsell to undertake; then Care, to manage; and Industry, to performe; and in the next place, where there is ability and strength to oppose, and Vertue to direct, Victory consequently is alwayes at hand ready to crowne the undertaking.

Upon the Hances of the waste [the rising curve from the waist of the ship to the quarterdeck] are foure Figures with their severall properties: Jupiter riding upon an Eagle, with his Trisulk (from which hee darteth Thunder) in his hand; Mars with his Sword and Target, a Foxe being his Embleme: Neptune with his Sea-horse, Dolphin, and Trident: and lastly Aeolus upon a Camelion (a beast that liveth onley by the Ayre) with the foure Windes, his Ministers or Agents, the East, call’d Eurus, Subsolanus and Apeliotes: the North-winde, Septemtrio, Aquilo, or Boreas: the West, Zephrus, Favonius, Lybs, and Africus: the South, Auster, or Notus.

I come now to the Stearne, where you may perceive up the upright of the upper Counter, standeth Victory in the middle of the Frontispiece, with this general Motto, Validis incumbite remis [Place your weight upon strong oars]: It is so plaine, that I shall not need to give it any English interpretation: Her wings are equally disply’d; on one Arme she weareth a Crowne, on the other a Laurell, which imply Riches and Honour: in her two hands she holdeth two Mottoes; her right hand, which pointeth to Jason, beares this Inscription, Nava, (which word howsoever by some, and those not the least opinionated of themselves, mistaken) was absolutely extermin’d, and excommunicated from all Grammaticall Construction, nay, Jurisdiction; for they would not allow it to be Verbe, or Adverbe, Substantive, nor Adjective: and for this I have not onely behind my back bin challenged, but even Viva voce taxed, as one that had writ at randum, and that which I understood not. But to give the world a plenary satisfaction, and that it was rather their Criticisme, than my ignorance, I intreate thee Reader, but to examine Riders last Edition of his Dictionary, corrected, and greatly augmented by Mr. Francis Holy-oke, and he shall there read Navo, navas, (and therefore consequently nava in the Imperative Mood) ex navus, that is, to imploy with all ones power, to act, to ayde, to helpe, to indeavour with all diligence and industry; and therefore not unproperly may Victory point to Jason, being figured with his Oare in his hand, as being the prime Argonaut, and say Nava, or more plainely, Operam nava [Work on the ship]; for in those Emblematicall Mottoes quod subintelligitur, non deest [what is implied is not lacking]. Shee pointeth to Hercules on the sinister side, with his club in his hand, with this Mottto, Clava [Club]; as if she should say, O Hercules, be thou as valiant with thy Club upon the Land, as Jason is industrious with his Oare upon the Water. Hercules againe pointing to Aeolus, the god of Windes, saith Flato [Blow]; who answereth him againe, Flo: Jason pointing to Neptune, the god of the Seas, (riding upon a Sea-horse) saith Faveto; to whom Neptune answereth, No: These words Flo, and No, were also much excepted at, as if there had beene no such Latine words, till some better examining their Grammar Rules found out Flo, flas, flavi, proper to Aeolus, and No, nas, navi, to Neptune, &c.

In the lower Counter of the Sterne, on either side of the Helme is this Inscription,

Qui mare, qui fluctus, ventos, naves[que] gubernat,

Sospitet hanc Arcam Carole magne tuam.

Thus Englisht:

He who Seas, Windes, and Navies doth protect,

Great Charles, thy great Ship in her course direct.

There are other things in this Vessell worthy remarke, at least, if not admiration; namely, that one Tree, or Oake made foure of the principall beames of this great Ship, which was Forty foure foote of strong and serviceable Timber in length, three foote Diameter at the top, and Ten foot Diameter at the stubbe or bottome.

Another, (as worthy of especiall Observation is) that one peece of Timber which made the Kel-son, was so great, and weighty, that 28. Oxen, and 4. Horses with much difficulty drew it from the place where it grew, and from whence it was cut downe, unto the water-side.

There is one thing above all these, for the World to take especiall notice of, that shee is, besides her Tunnage, just so many Tuns in burden, as their have beene Yeeres since our Blessed Saviours Incarnation, namely, 1637. and not one under, or over: A most happy Omen, which though it was not at the first projected, or intended, is now by true computation found so to happen.

It would bee too tedious to insist upon every Ornament belonging to this incomparable Vessel, yet thus much concerning Her outward appearance. She hath two Galleries of a side, and all of most curious carved Worke, and all the sides of the ship are carved also with Tropies of Artillery and Types of honour, as well belonging to Land as Sea, with Symboles, Emblemes, and Impresses appertaining to the Art of Navigation: as also their two sacred Majesties Badges of Honour, Armes, Eschutchions, &c. with severall Angels holding their Letters in Compartments: all which workes are gilded quite over, and no other but gold and blacke to bee seene about her. And thus much in a succinct way I have delivered unto you concerning her inward and outward Decorements. I came now to Discribe her in her exact Dimension.

Her Length by the Keele, is 128 foot or there about, within some few inches. Her mayne breadth or widenesse from side to side 48. foote. Her utmost length from the fore-end of the Beake-head, unto the after end of the Sterne, a prora ad puppim [from prow to stem] 232. foote, she is in height from the bottome of her Keele to the top of her Lanthorne seaventy sixe foote, she beareth five Lanthornes, the biggest of which will hold ten persons to stand upright, and without shouldring or pressing one the other.

She hath three flush Deckes, and a Fore-Castle, an halfe Decke, a quarter Decke, and a round-house. Her lower Tyre hath thirty ports, which are to be furnished with Demy-Cannon and whole Cannon through out, (being able to beare them). Her middle Tyre hath also thirty ports for Demi-Culverin, and whole Culverin: Her third Tyre hath Twentie sixe Ports for other Ordnance, her fore-Castle hath twelve ports, and her halfe Decke hath fourteene ports; She hath thirteene or foureteen ports more within Board for murdering peeces, besides a great many Loope holes out of the Cabins for Musket shot. She carrieth moreover ten peeces of chase Ornance in her, right forward; and ten right aff, that is according to Land-service in the front and the reare. She carrieth eleaven Anchors, one of them weighing foure thousand foure hundred, &c. and according to these are her Cables, Mastes, Sayles, Cordage; which considered together, seeing his Majesty is at this infinite charge, both for the honour of this Nation, and the security of his Kingdome, it should bee a great spur and incouragement to all his faithful and loving Subjects to bee liberall and willing Contributaries towards the Ship-money.

I come now to give you a particular Denomination of the prime Worke-men imployed in this inimitable Fabricke; as first Captayne Phines Pett, Over-seer of the Worke, and one of the principal Officers of his Majesties Navy; whose Ancestors, as Father, Grand-father, and Great-Grand-father, for the space of two hundred yeares and upwards, have continued in the same Name, Officers and Architectures in the Royall Navy; of whose knowledge, experience, and judgement, I can not render a merited Character.

The Maister Builded is young M. Peter Pett, the most ingenious sonne of so much improoved a Father, who before he was full five and twenty yeares of age, made the Model, and since hath perfected the worke, which hath won not only the approbation but admiration of all men, of whom I may truely say, as Horace did of Argus, that famous Ship-Master, (Who built the great Argo in which the Grecian Princesse Rowed through the Hellespont, to fetch the golden Fleece from Colchos).

Ad Charum Tritonia Devolat Argum,

Moliri hanc puppim iubet

that is, Pallas her selfe flew into his bosome, and not only injoin’d to the undertaking, but inspired him in the managing of so exquisite and absolute an Architecture.

Let me not here forget a prime Officer Master Francis Shelton, Clerke of the Checke, whose industry and care, in looking to the Workmen imployd in this Architecture, hath beene a great furtherance to expedite the businesse.

The Master Carvers, are John and Mathias Christmas, and Sonnes of that excellent Workeman Master Gerard Christmas, some two yeeres since deceased, who, as they succeed him in his place, so they have striv’’d to exceed him in his Art: the Worke better commending them than my Pen is any way able, which putteth me in minde of Martiall, looking upon a Cup most curiously Carved.

Quis labor in phiala? Docti Mios? anne Mironis?

Mentoris an manus est? an Polyclete tua?

What Labour’s in this curious Bowle?

Was’t thine, O Myus tell?

Myrons? Mentors? or Polyclets?

He that can carve so well.

And I make no question, but all true Artists can by the view of the Worke, give a present nomination of the Workmen. The Master-Painters, Master Joyner, Master Calker, Master Smith, &c. all of them on their severall faculties being knowne to bee the prime Workmen of the Kingdome, selectedly imployd in this Service.

Navis vade, undae fremitum posuere minaces,

Et Freta Tindaridae spondent secura gemelli,

Dessuetam iubent pelago decurre Puppim,

Auster et optatas afflabit molliter auras.

[Loosely: Go to the ships, though rough seas threaten / And Castor and Pollux will protect you through the narrow straits / Having ordered this special ship’s safe passage / The winds will blow fair.]

An Epigram upon his Majesties Great Ship, lying in the Docke at Wooll-witch, Thomas Heywood – complete text

What Artist tooke in hand this Ship to frame?

Or Who can guesse from whence these tall Okes came?

Unlesse from the ful grown Dodonean grove,

A Wildernesse sole sacred unto Jove.

What Eye such brave Materials hath beheld?

Or by what Axes were these Timbers feld?

Sure Vulcan with his three Cyclopean Swaines,

Have forg’d new Metalls from their active braines,

Or else, that Hatchet he hath grinded new,

With which he cleft Joves skull, what time out flew

The arm’d Virago, Pallas, who inspires

With Art, with Science, and all high desires.

Shee hath (no doubt) raptur’d our Undertaker

This Machine to devise first, and then make her.

How else could such a mighty Mole be rais’d?

To which Troyes horse, (by Virgil so much prais’d,

Whose bulke a thousand armed me contein’d)

Was but a toy, (compar’d) and that too feign’d

For she beares thrice his burden, hath roome, where

Enceladus might rowe, and Tition steere:

But no such Vessell could for them be made,

Had they intent, by Sea the gods to invade.

The Argoe, stellified because ’twas rare,

With this Ships long Boat scarcely might compare.

Yet sixty Greek Heroes even in that

With Oares in hand, upon their Transtrae sate.

Her Anchors, beyond weight, expanst, and wide,

Able to wrestle against Winde, and Tyde:

Her big-wrought Cable like that massie Chaine

With which great Xerxes bounded in the Maine

’Tweene Sestos and Abidos, to make one,

Europe and Asia, by that Lyne alone.

Her five bright Lanthorns luster round the Seas,

Shining like five of the seven Hyades:

Whose cleare eyes, should they (by oft weeping) fayle

By these, our Sea-men might finde Art to sayle.

In one of which, (which bears the greatest light)

Ten of the Guard at once may stand upright:

What a conspicuous Ray did it dart then?

What more than a Titanian Luster, when

Our Phoebus, and bright Cinthia jointly sphear’d

In that one Orbe, together both appear’d:

With whom seven other Stars had then their station,

All luminous, but lower Constellation.

That Lampe, the great Colosse held, who bestrid

The spacious Rhodian Sea-arme, never did

Cast such a beame, yet Ships of tallest size,

Past, with their Masts erect, betweene his thighes,

Her maine Mast like a Pyramis appeares,

Such as the Aegyptian Kings were many yeeres,

To their great charge erecting, whilst their pleasure

To mount them hie, did quite exhaust their treasure.

Whose brave Top top-top Royal nothing barres,

By day, to brush the Sun; by night, the Starres.

Her Maine-sayle, (if I doe not much mistake)

For Amphetrite might a Kirtle make:

Or in the heate of Summer be a Fanne,

To coole the face of the great Ocean.

Shee being angry, if she stretch her lungs,

Can rayle upon her enemy, with more Tongues

(Louder than Stentors, as her spleene shall rise)

Than ever Junoes Argus saw with his eyes.

I should but loose my selfe, and craize my braine,

Striving to give this (glory of the Maine)

A full description, though the Muses nine

Should quaffe to me in rich Mendaeum Wine.

Then O you Marine gods, who with amaze,

On this stupendious worke (emergent) gaze,

Take charge of her, as being a choise Jemme,

That much out-valews Neptunes Diadem.

A description of the launch, added for the second edition, Thomas Heywood (1638)

Some things in the premises have been omitted, which upon better information and recollection are necessarily to be considered of in the setting out of this great Ship, neither can any justly blame the first Copy of error or in defective, in regard those places belonging unto Her, were not then disposed of, which were since, by his Majesties carefully conferred upon such prime Officers, as are the most expert and absolute to take the charge of this unparalleled and incomparable Vessel: Namely, first Captain William Cooke Master, secondly, Master Rabnet Boatswaine, thirdly, Captain Taylor Maister Gunner, fourthly, Maister Phil. Ward Purser, fifthly, Joseph Pet Maister Carpenter, with divers others not here mentioned, because they would seem tedious to the Reader, And though there appeared some difficulty in the first attempt of her launching, by reason of the breaking of so many Cables, and of a contrary Wind, which hindered the coming in of the Tide to its full height: yet in the second attempt, she so freely offered herself to the River, as if weary of being so long imprisoned in the Dock, she voluntarily exposed herself to the Channel, of which (next under God,) she (according to her name) is the sole Sovereign and Commander, of which there is the greater hope, in regard that no great ship or smaller Bark which ever floated upon the river of Thames that hath, or can with more dexterity or pleasure play with the Tide: She, though of that vast burden, yet dancing upon the River as nimbly as a small Catch or Hoy, which indeed hath proved somewhat above expectation, bearing the weight of one thousand six hundred thirty seven Tun, besides her other tackling.

A second thing of which some especial notice may bee taken, is, that young Mr. Peter Pet the Maister Builder, hath to his great expense and charge, to show that this excellent Fabric is not to be equaled in the World again: and to give a president to all Foreign Ship-architectures, how they shall dare to undertake the like, hath lately published her true Effigies or portraiture in Sculpture, grav’d by the excellent Artist Mr. John Paine, dwelling by the postern gate near unto Tower-hill, of whose exquisite skill, as well in drawing and painting, as his Art in graving, I am not able to give a Character answerable unto his merit.

And though some too apish and new fangle of our own Nation thinks nothing rare, or indeed scarce worthy approbation, which is not wrought by strangers: yet let this Sovereign of the Seas, in it’s own ability, decrement, and all sufficiently, proclaim to the World (being both beguine and finish by our own Natives and Country-men) that for Timber, Tackles, Cables, Cordage, Anchors and Ordnance, &c. For the Surveyor, Builder, Carvers, Painters, Founders, Smiths, Carpenters, Graver, and other prime Officers belonging unto her, never was any Vessel so well accommodated.

Acknowledgments

This entry draws particularly on John Mitchell’s The Herring, Its Natural History and National Importance (1864), Robert Cowie’s Shetland: Descriptive and Historical,Thomas Wemyss Fulton’s The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) and John Rawson Elder’s The Royal Fishery Companies of the Seventeenth Century (1912).

I am deeply grateful to my good friend Steve Hinton for his patient explanations of the mathematics at the heart of land’s kenning calculation.

See also

- BATTLE OF THE HERRINGS (1429)

- BEUCKEL, Willem

- BOHUSLÄN FISHERY

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BUSS

- DIVINE PROVIDENCE

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- ENGLAND’S PATH TO WEALTH AND HONOUR

- FASTING

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- HERRING INDUSTRY BOARD

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- LOCKMAN’S VAST IMPORTANCE

- RED HERRING

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- SCANIA FISHERY

- SMITH, ADAM: WEALTH OF NATIONS

- SUFFERING SALTWORKERS OF SHIELDS

- WEDGWOOD

- WHITE HERRING

- ZUYDERZEE