Including a complete, illustrated translation of Paul Neucrantz’ C17th treatise on the herring together with notes on his sources

NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

The herring is the King, or even Emperor of Fishes. It is scientifically fascinating and, historically, has been of huge economic significance. But it has also always been funny.

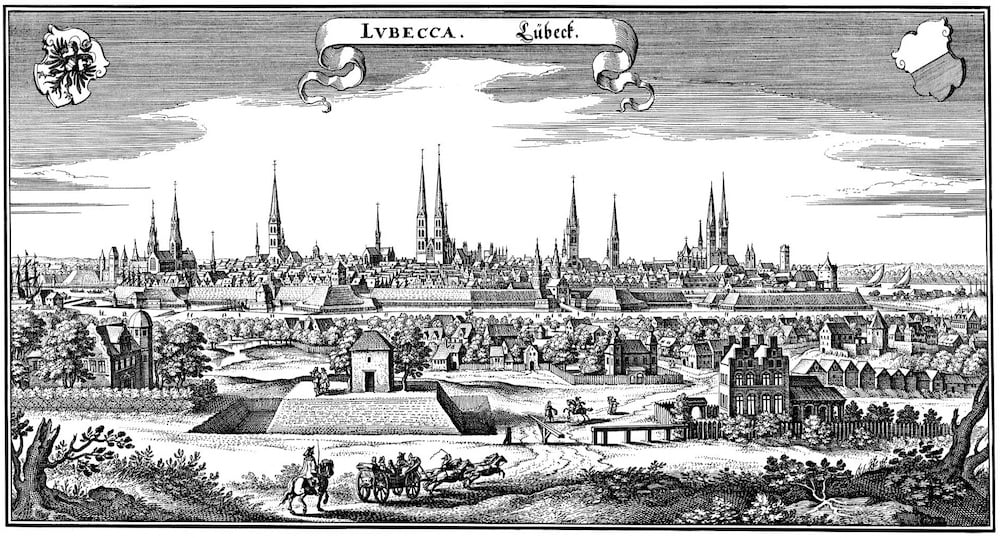

In 1654 the splendid council of the Republic of Lübeck published Neucrantz’ learnedly comic celebration of the fish he loved: De Harengo exercitatio medica in qua principis piscium exquisitissima bonitas summaque gloria asserta et vindicata (A Medical Treatise upon The Herring, in which the excellent virtue and supreme glory of the Emperor of Fishes are presented and proved). The publication was sponsored by Joachim Wild, bookseller of Rostock.

Paul Neucrantz was a Doctor of Philosophy and Medicine of Rostock, but lived and worked in Lübeck and was very much a part of the medical, scientific and cultural scene there. The city had a sense of the herring’s role in its glory days as capital of the Hanseatic League, but by the mid C17th this variable federation of European cities was crumbling. The Scania herring fishery, with which Lübeck had been so involved, had gone.

On Herring is a defence in fifteen chapters of a fish fallen from grace.

It’s witty, playful and determinedly out of all proportion to the subject demands of a cheap commonplace of the fish market. A written work over which he laboured, ensuring he’d dotted every i and crossed every t, but its origins are in an extensive speech he performed to an audience of his peers and patrons.

Neucrantz can’t help throwing in a fascinating side track here, a little known fact there. He takes every opportunity to demonstrate the dazzling range of his sources and authorities. If you want an idea of C17th medicine and natural history or of late Hanseatic academic culture, it provides a beautifully rich snapshot.

In addition to Leviticus, Deuteronomy, the Gospel According to Mark and Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, he draws on well over 100 sources by over 90 individual writers. Half of his authorities, Latin, Greek and translated from Arabic, were not aware of the herring – he spends a whole chapter conclusively proving this – but he’s also on top of contemporary thinking, particularly in medicine. He draws on correspondence with the great Dutch surgeon Nicolaes Tulp, who, as well as being painted by Rembrandt, was clearly a fellow enthusiast for the herring. And he conducted his own research among the fishermen and fish sellers of Lübeck’s fishing port Travemünde and on the specimens he bought from them.

His treatiselooks at the herring and its natural history; its involvement in economic and political history; in folklore and cultural tradition; its preservation, recipes and medical uses.

Some of the questions he raises have only been fully addressed in the C20th and C21st. He points to what have become recognised as the mixed herring populations in the Southern North Sea, a flaw in the then prevalent theory of a single, grand, divinely provident migration. He devotes a whole chapter to the ‘squeaking of herrings’, the communicative ‘farts’ explained by Wilson, Dill and Batty in 2003 – a phenomenon which in the 1980s Swedish naval intelligence considered evidence of Soviet submarine activity.

Swedish naval intelligence was probably unaware of Neucrantz and got Hakan Westerberg and Magnus Wahlberg to analyse its recordings. They were probably not aware of Neucrantz either.

The miracle of digital publication means the C17th academic Latin text is now available online (see link below) but Neucrantz is still largely unknown. Did you mean Marantz or Neurotin? Google asks. When I last searched, the herripedia occupied the two top places, you didn’t come across the Latin text until No 8 and three of the intervening five were for a Neukrantz. This is how the world treats herring obsessives.

On the text and translation

Neucrantz’ treatise is competitive, proving points against Dr Grakius, who had given a disrespectful speech on the subject of the herring at a wedding in Thurovia – the Swiss canton Thurgau on the southern shores of Lake Constance. Grakius had had an unfortunate experience after eating the fish.

In marshalling his evidence, Neucrantz gives chapter and verse. Today even the most enthusiastic harengophile can lose the will to live in the detail of the references. The translation aims at making the work accessible and these details have been pared back, often to just the author. Instead, a list of the sources has been provided, briefly saying who each one is and indicating the specific works referenced. It’s interesting to read just on its own.

In the late 1990s, I came across a mention of De harengo in J Travis Jenkins’ The Herring and the Herring Fisheries (1927). I ordered a photocopy from the British Library. Foolishly, Ingrid O’Mahoney, a friend of my sister, agreed to attempt a literal translation. C17th German academic Latin is not classical Latin and it was very generous of her.

Off and on, I struggled with it. The more I found out about herrings, herring history and herring thinking, the more it has become possible to disentangle what Neucrantz is saying. When I came back to it in 2018, the resources of the internet proved transformational. For a start, you can check out a lot of the references.

As I write, I don’t think there’s another translation available in English or German, but the floodgates might yet open. If anyone out there is a fluent reader of C17th academic Latin, corrections are always welcome.

Notes on Neucrantz’ sources

Joannes Actuarius (c 1275 – c 1328) Byzantine physician in Constantinople; De actionibus et affectibus spiritus animalis, ejusque nutritione (On the Spirit of Animal Nutrition).

Aelian or Claudius Aelianus (c 175 – c 235 AD) Roman author of De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals).

Aëtius of Amida (late C5th, early C6th AD) Byzantine Greek physician; Sixteen Books on Medicine

Alexander of Tralles (c 525 – 605 AD) Physician in Anatolia; Twelve Books on Medicine.

Ulisse Aldrovandi or Aldrovandus (1522 – 1605 AD) Italian naturalist, regarded by Linnaeus as the father of natural history studies; Diversità di cose naturali (Natural History).

Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Majusi or Masoudi (C10th AD) Referred to by Neucrantz as Haly Abbas, a Persian physician and psychologist, possibly Zoroastrian; Kitab al-Maliki or The Complete Art of Medicine.

Al-Razi or Abu Bakr Muhammed ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (854 to 925 or 932 AD) Persian polymath, physician and philosopher, known to Neucrantz in the latinised name Rases (also Rhazes or Rasis); Neucrantz refers to a Compendium of Rules for Eating and Drinking, which may be the Manfe’ al aghzie va mazareha or Benefits of Food and its Harmfulness but may be drawn from advice in his medical encyclopaedia, the Kitab al-Hawi fi al-Tibb, translated into Latin as Liber Continens; he also specifically refers to the Kitab al-Mansouri, the Book on Medicine dedicated to his patron.

Al-Zahrawi or Abu al-Qasim ibn al-‘Abbas al-Zahrawi al-Ansari (930 – 1013 AD)Referred to by Neucrantz in his latinised name Abulcasis, physician, surgeon and chemist in Adalusia, considered the greatest surgeon of the Middle Ages; Kitab al-Tasrif, a medical encyclopaedia; Neucrantz refers to him in the context of cold roast fish and the 30 volumes include his thoughts on nutrition, although Vol. 30, on surgery, was the most widely distributed in translation.

Ambrose of Milan or St Ambrose (c 399 – 397 AD), Of Belgian origins he was Bishop of Milan; Hexameron (The Six Days of Creation).

Androsthenes (C4th BC); Explorer and an admiral under Alexander the Great; The Navigation of the Indian Sea.

Antiphanes (c 408 – 334 BC), Greek comic poet; Boutalion (On Rustic Matters) – work included in Athenaeus Deipnosophistae.

Apicius (C1st or C5th AD) Sometimes said to be by, but definitely named after a C1st Roman gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius – from whom some of the recipes may have come – the only surviving copy dates from C5th, so it may have just taken his name; also called De re coquinaria or De re culinaria (On the Subject of Cooking) a collection of Roman recipes.

Apollodorus the Athenian (c 180 – after 120 BC) Greek scholar and writer; Neucrantz probably refers to The Catalogue of Ships.

Aristophanes (c 446 – 386 BC) Greek comic playwright; The Acharnians, Wealth.

Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) Greek philosopher, later revered by Muslim scholars as The First Teacher and then in the European Renaissance – a kind of No 1 authority for Neucrantz, even though he did not know the herring; On Breathing (generally regarded as not by Aristotle, but included in the Corpus Aristotlelicum); History of Animals; Metaphysics; Meteorology.

Arnobius of Sicca (C3rd/C4th) Tunisian Berber Christian apologist; Adversus nationes (Against the Pagans).

Athenaeus of Naucratis (Late C2nd/early C3rd) Greek rhetorician and grammarian; Deipnosophistae (The Dinner Table Philosophers or Feast Wisdom), 15 books referring to and quoting roughly 800 classical writers and 2,500 works, many of which would otherwise have been lost entirely – including the comic food poet Archestratus (C4th BC).

St Basil of Caesarea or Basil the Great (329/30 – 379 AD) Bishop in Cappadocia, influential in establishing Nicene orthodoxy in the early Christian church (and opposing heresy); Hexameron (The Six Days of Creation).

Pierre Belon or Bellonius (1517 – 1564), French traveller and naturalist De Aquatilabus, 1553 (On the Nature and Diversity of Fish or La Nature et Diversite des Poissons).

Pieter de Bert or Petrus Bertius (1565 – 1629 AD) Flemish philosopher, geographer and cartographer; Neucrantz refers to a description of Flanders, which may have been included in his map book Tabularum geographicarum contractarum (1603) or his Commentarium rerum germanicarum (German Commentaries, 1616).

Boethius or Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius (c 477 – 524 AD) Roman philosopher; The Consolation of Philosophy, composed while in prison before being executed by Theodoric the Great.

Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn (1612 – 1653) Dutch scholar and writer; Neucrantz refers to his Navigationibus Hollandorum adversus Pontum Heuterum (Dutch Voyage to the Black Sea), but his Town Atlas of Holland identifies C12th participation in the Scania herring fairs.

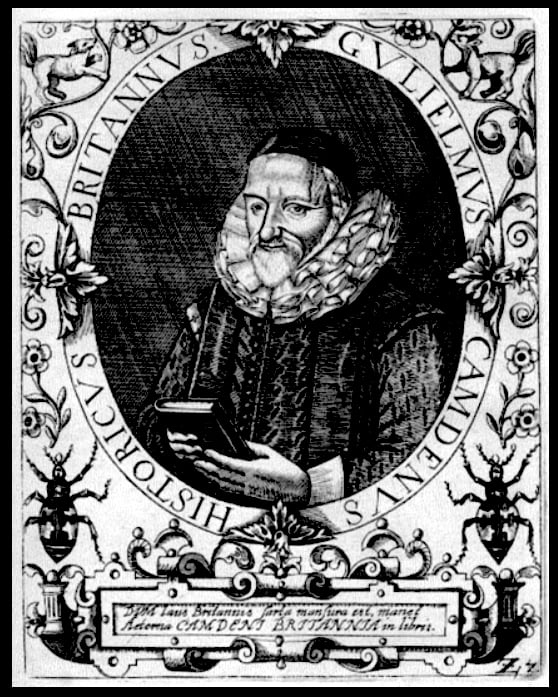

William Camden (1551 – 1623 AD) English antiquarian, historian and writer; Britannia, first published in 1586, but Neucrantz is drawing on the 1607 edition, which, probably prompted by James I’s obsession, includes an account of herring migration as divine providence aimed at Britain rather than The Netherlands (see Divine Providence).

Isaac Casaubon (1559 – 1614) French scholar, regarded by some at the time as the most learned man in Europe; an editor and commentator on Athenaeus’ Feast Wisdom.

Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c 25 BC – c 50 AD) Roman encyclopaedist; De Medicina, believed to be just the surviving section of a much larger work.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC) Roman statesman, philosopher and scholar; Tusculan Disputations, a series of five books named after the location of his villa, covering death, pain, grief, vexations and virtue as a route to happiness.

Columella or Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (4 – c 70 AD) Roman writer on agriculture, born in Cadiz; De Re Rustica (On Rural Affairs).

Cyril of Alexandria (c 376 – 444 AD) Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria, saint and prolific writer, he had a bad relationship with the Nestorians and the Catholic Church, who didn’t give him a saint’s day until 1882; Unspecified works.

Pietro d’Abano or Petrus Aponensis (c 1257 – 1316 AD) Italian philosopher and professor of medicine in Padua; De venenis eorumque remediis (On Poisons and Their Remedies).

Democritus (c 460 – c 370 BC) Greek philosopher from Thrace – some consider him the father of modern science, although Plato wasn’t keen – he wrote extensively on nature and the natural sciences; unspecified works, but only fragments survive and Neucrantz may have drawn on the through citations in the works of others.

Pedanus Dioscorides (c 40 – 90 AD) Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist from what is now South West Turkey; De Materia Medica.

Empedocles (c 494 – c 434 BC) Greek philosopher from Sicily; On Nature.

Eustathius of Thessalonica (c 1115 – 1196 AD) Byzantine Greek scholar and archbishop, he became a saint in 1988; Commentary on the Iliad.

Festus or Sextus Pompeius Festus (C2nd) Roman grammarian; De verborum significantu.

Aelius Galenus or Galen (129 – 161 AD) Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher from what is now Western Turkey, hugely significant medical authority, not least for his is approach to dissection; Various from a huge number of works on medicine, including De Usus Partium Corporis Humani (The Function of the Parts of the Human Body).

Theodorus Gaza or Theodore Gazis (1398 – c 1475) Greek scholar, translator of and commentator on Aristotle; Neucrantz is probably referring to his commentary on either Aristotle’s De partibus animalium or his De generatione animalium.

Conrad Gessner or Conradus Gesnerus (1516 – 1565 AD) Swiss physician and naturalist; Historia Animalum (1549).

Paolo Giovio or Paulus Jovius (1483 – 1552 AD) Italian physician and writer; De romanis piscibus, 1524 (On Fish in Rome) and Descriptio Britannae, Scotiae, Hiberniae et Orchadum,1548.

Saxo Grammaticus (c 1160 – 1220) Danish historian, theologian and writer; Gesta Danorum (Story of the Danes) – Saxo Grammaticus is referenced by many herring historians for his description of massive shoals in The Sound, which may or may not have been linked to the emergence of the Scania fishery.

Ludovico Guicciardini (1521 – 1589 AD) Italian writer and merchant; Description of the Low Countries, 1567).

Hippocrates (c 460 – c 370 BC) Greek physician from Kos, another Father of Medicine, founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine and possible author of the Hippocratic Oath, although it may have been written after his death; Neucrantz refers to a number of works included in the Corpus Hippocraticum (The Hippocratic Corpus) – whether this collection of texts is by Hippocrates has not been established.

Caspar Hofmann (1572 – 1648) Medical academic; Institutum medicarum (1645)

Horace or Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 – 8 BC) Roman poet; Satires.

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon, Isaac Judaeus or Isaac Israelites (c 832 – 932 AD) Jewish physician and philosopher from Cairo, writing in Arabic; De particularibus diaetis or Diaetae Universales,translated into Latin by Constantine the African in C11th from the Kitab al-Adwiyah al- Mufradah wa’l-Aghdhiyah (his work was also translated into Hebrew and Spanish).

Ibn Sina, Abu Ali Sina or Pur Sina (c 980 – 1037) Persian polymath, one of the most significant physicians, scientists, thinkers and writers or the Islamic Golden Age and regarded as the father of early modern medicine – known to Neucrantz and in most of the European tradition as Avicenna; The Book of Healing, The Canon of Medicine.

Isidore of Seville or Isidorus Hispalensis (c 560 – 636 AD) Scholar and Archbishop; Etymologiae (The Etymology, an encyclopaedia) aka Origines.

Adriaen de Jonghe or Hadrianus Junius (1511 – 1575 AD) Dutch physician and antiquarian; Batavia and Nomenclature – primarily known in the herring world for the former, which suggests the supposed herring migration down the eastern coasts of Scotland and England was a sign of divine providence aimed at the Dutch state (see Divine Providence).

Jordanes, Jordanis or Jornandes (C6th AD) Byzantine historian; Getica, a history of the Goths, written c 550 AD.

Diogenes Laërtius (C3rd AD), Greek biographer of whom little is known; Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.

Joost Lips or Justus Lipsius (1547 – 1606) The text reference is to Centur: 3, epist 51, possibly from Variarum lectionum (Various Lessons, 1567).

Livy or Titus Livius (c 60 BC – 17 AD) Roman Historian; Ab Urbe Condita Libri (The History of Rome from its Foundation, which includes The War with Hannibal)

Lucretius or Titus Lucretius Carus (99 – 55 BC) Roman poet and philosopher; De Rerum Natura or On the Nature of Things.

Macrobius or Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (C5th AD) Roman writer also referred to by Neucrantz as Clarissimus the Interpreter; Saturnalia, a series of dialogues between learned men at a banquet.

Olaus Magnus (1490 – 1557 AD) Swedish writer and cartographer; Carta Marina (A Marine Map and Description of the Northern Lands and their Marvels, 1539); Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (A Description of the Northern Peoples, 1555).

Martial or Marcus Valerius Martialis (c 38 – 104 AD) Roman poet from Spain; Epigrams.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli or Matthiolus (1501 – 1577 AD) Italian physician, naturalist and botanist, the first to describe allergy to cats and the first in Europe to document the tomato; Discorsi (Speeches).

Nonius Marcellus (C4th / C5th AD) Roman grammarian; De compendiosa doctrina (Compendium of Teaching).

Luis Mercado (1525 – 1611 AD) Spanish physician; Neucrantz refers to The nature and cure of putrid fevers, which may be in his work De Febrium.

Nemesius of Emesa (C4th/C5th AD) Greek Christian philosopher drawing on Aristotle and Galen, Bishop of Emesa (present day Homs in Syria); De natura hominis (On Human Nature).

Oppian of Corycus (C2nd AD) Greco-Roman poet from Caesarea or Corycus in what today is South West Turkey; Halieutica (On Fishing).

Oribasius (320 – 403 AD) Greek physician and medical writer, the Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate’s personal doctor; Collectiones Medicae (Medical Collections).

Paul of Aegina or Paulus Aegineta (c 625 – c 690 AD) Byzantine Greek physician; Medical Compendium in Seven Books.

Gaius Petronius (27 – 66 AD) Roman courtier in the reign of Nero (which can’t have been easy); Satyricon – he is believed to have been the author.

Plato (c 427 – 347 BC) Greek philosopher, who learned from Socrates and taught Aristotle; The Symposium – Neucrantz also refers to Marsilio Ficino‘s De Amore (1484), a commentary on The Symposium.

Titus Maccius Plautus (c 254 – 184 BC) Roman playwright; Neucrantz refers to his play Aulularia, generally translated as The Pot of Gold, Poenulus or The Little Carthaginian and the fragmentary play, Parasitus Medicus or The Parasite Physician.

Pliny the Elder or Gaius Plinius Secundus (23/24 – 79 AD) Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher; Naturalis Historia, (Natural History).

Pliny the Younger or Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (61 – c113 AD) Pliny the Elder’s nephew, Roman lawyer, magistrate and author; Neucrantz refers to a letter to Oppian on the subject of hunting.

Plutarch (c 46 – c 120 AD) Greek philosopher, biographer and essayist; De sollertia animalium (On the Intelligence of Animals) included in Moralia.

Pomponius Mela (c 43 AD) Roman geographer from Tingentera (Algeciras); De Situ Orbis.

Johannes Isaac Pontanus (1571 – 1639 AD) Dutch historian; Discussiones Historicae, 1637.

Priscian or Priscianus Caesariensis (late C5th – early C6th) Latin grammarian from what is now Algeria; Institutes of Grammar, the

Theophilus Protospatharius or Philotheus (C7th) Greek medical writer about whom little is known; De Corporis Humani Fabrica (On the Parts of the Human Body), an abridged and altered version of Galen’s De Usus Partium Corporis Humani, and a Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates (uncertainly attributed to him).

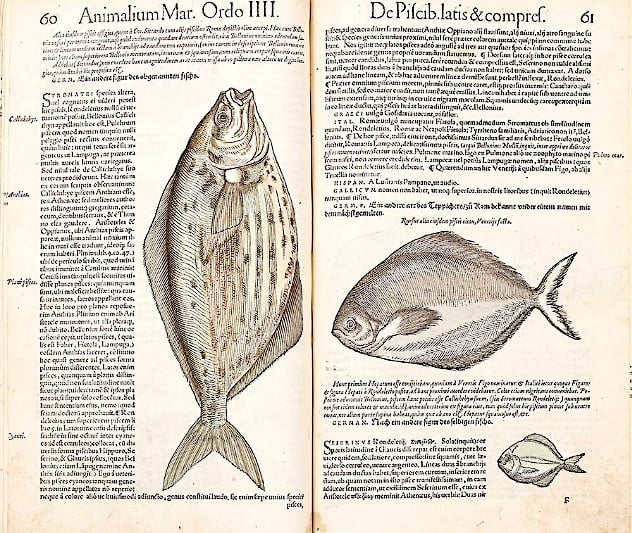

Guillaume Rondelet or Rondelatus (1507 – 1566) French anatomist, naturalist, botanist and zoologist; Libri de piscibus marinis in quibus verae piscium effigies expressae sunt, 1554 (The Book of Marine Fish, referred to as On Fish).

Boudewijn Ronsse or Balduinus Ronsseus (1525 – 1597) Dutch physician and medical writer; Epistolae medicinales (1618).

Johannes Russus (untraced) Annals of Lübeck.

Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484 – 1558 AD) Italian scholar and physician; Exotericarum exercitationum, 1557 (The Exercises); Festus, Letters.

Stephan von Schoneveld or Stephanus Schoneveldus (C16th / C17th) German naturalist, possibly a physician and from Hamburg; Neucrantz refers to a Book About Fishes, which will be The Ichthyology and Nomenclature of Sea and River Creatures in the Duchy of Schleswig Holstein (1624).

Martin Schoock or Martinus Schookius (1614 – 1669 AD) Dutch historian and philosopher; Neucrantz refers to a work on the Dutch states or provinces, which is almost certainly Belgium federatum, sive Distincta descriptio reip. federati Belgii (1652).

School of Salerno or Schola Medica Salernitana (founded in C9th AD, but still in operation in C17th) Medical school which played a major role in translating and disseminating Ancient Greek, Arabic and Jewish texts; Neucrantz refers to a ‘book on the preservation of health’, which is probably the Regimen sanitatis Salernitatum (C12th or C13th).

Seneca the Younger or Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BC – 65 AD) Spanish Roman philosopher and playwright; Naturales Quaestiones (Questions of Nature).

Simon Sethus (C16th) Greek writer on food; On the Qualities of Food (1561).

Gaius Julius Solinus (C3rd AD) Latin grammarian and encyclopaedist; De mirabilis mundi (The Wonders of the World) aka Polyhistor (Multi-descriptive) and Collectanea rerum memorabilium (Collection of Curiosities).

Sophocles (c 497 – 405 BC) Greek playwright; Ajax.

Strabo (c 63 BC – c 24 AD) Greek geographer, philosopher and historian; Geographica.

Publius Cornelius Tacitus (c 56 – 120 AD) Roman historian; Germania (On the Origin and Location of the German Tribes); Annales (The Annals).

Theophrastus (c 371 – c 287 BC) Greek philosopher; On Character and Ethics (Characters); On Fish That Live on Land; On the Reason for Plants.

Nicolaes Tulp or Tulpius (1593 – 1674 AD) Celebrated Dutch surgeon; Neucrantz refers to his Observationes Medicae (1641), but also was in a direct correspondence with him, which included specific letters, probably in response to a request from Neucrantz, on the subject of herring; see Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632).

Adrien Turnèbe, Adrianus Turnebus or Adrien Tournebeuf (1512 – 1565 AD) French classical scholar; Adversaria.

Valerius Maximus (C1st AD) Latin writer; Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium (Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings).

Varro, Marcus Terentius Varro or Varro Reatinus (116 – 27 BC) Roman scholar and writer; De Lingua Latina or On the Latin Language and, possibly, Rerum rusticarum or On Agricultural Topics.

Virgil (70 – 19 BC) Roman poet; Aeniad.

Franciscus Vicquius (C16th/C17th) Dutch doctor, a contemporary of Nicolaes Tulp, mentioned in his Observationes Medicae;(unable to trace his non-Latinised name or relevant works).

Vincent of Beauvais, Vincentius Bellovacensis or Vincentius Burgundus (c 1184/1194 – c 1264) French Dominican friar and encyclopaedist; Speculum Naturale (The Mirror of Nature).

Gerhard von Wesel (1443 – 1510 AD) German merchant from Cologne; Neucrantz, mentions a description of Flanders.

Xenophon (431 – 354 BC) Greek military leader, philosopher and historian; Symposium or The Banquet, The Cyropaedia or The Education of Cyrus.

DE HARENGO

A Medical Treatise on the Herring

in which the most excellent good qualities and the greatest glory

of the Emperor of Fishes are published and proved

for the most splendid Council of the Republic of Lübeck

CHAPTER I

In which the reason for this book is explained

O, magnificent, most noble, learned and generous amongst men, my masters to whom all honour is especially due, until recently we hadn’t discussed the virtues of the herring. At the recent wedding in Thurovia, however, Master D Johannes Grakius gave us his thoughts On Herrings. He called them unpleasing and unhealthy fish.

Given to buying whole and ungutted, he’d eaten a fresh specimen, properly cooked, and suddenly he felt ill. There was a belching. There was a thunderous seizure of the bowels. And then there came the diarrhoea: like a deluge. In the light of this experience he decreed his abstinence from herring. No matter how reasonably priced, it was banished from his tables. And in his address he told us of those brave, but demoralised fishermen of Travemunde: they may catch it but they don’t like it! Any other fish is preferred.

Popular opinion seems to be with him, My Lords, when he argues eating herrings can lead to the fever. This is why mistresses of the house are expected to order them carefully gutted, cooked, only lightly salted and then marinated in vinegar and horseradish, its harmful effects thus countered. Boudewijn Ronsse says the herring acquired this unjustified reputation in his lifetime. Likewise, Stephan von Schoneveld, in the chapter on herrings in his Book About Fishes, argues, as a soft fish, it’s inclined to produce excrement and fevers among the incautious.

I had only recently asserted the exact opposite in my Purple Book on the Treatment of Malignant Fevers. Having surveyed the commentaries of doctors and natural historians on just about any fish they chose to mention, I feel duty bound to stick to my opinion, holding it to be well-founded: the herring is a fish of the most commendable virtue. Were I not to undertake this present and necessary defence of the chief of fishes, I should be dismissed as a lick-spittle toady, a man who’d deny the truth of anything.

According to The Characters of Theophrastus, to understand is to forgive. Perhaps this rambling introduction tests your patience, but I’ve been given this opportunity to respond and so I must ask for precisely this forgiveness. In what may, of course, be a dubious insertion into the surviving volume of Cornelius Nepos’ On the Lives of Great Men, Cato the Elder chides Aulus Albinus for his apologies: I have been welcomed by this town with such generosity and affection, I trust that I too might crave indulgence rather than address my crimes.

And so, exactly which kinds of argument should be marshalled before the noble rulers of our state, their own rich examples always suggestive of good taste? At a wedding the speeches should lead guests towards a sense of celebration. The vacuous and the inappropriate are not welcome here. The guest’s stomach shouldn’t feel bloated by food or by drink or by foolishness: these leave no other option but the sick bucket and the next day’s nausea and disgust for the world hanging in his head.

The gluttony we associate with the Boeotians is commented upon amusingly in Eubulus’ Antiope, Europa, Cercopes and Mysians. It is referred to by Diplonius and by Alexis, in Polybius’ The Histories, by Crates in Lamia, by Philaetetus and in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophos or Feast Wisdom.

Over-indulgence in drink is likewise mentioned by Pliny, who writes of the Parthians, that they gloried in it as if it were a virtue. St Basil the Great’s Speech Against Drunkenness and Luxury, extensively commented upon by Joost Lips, describes prodigious drinking bouts among the Greeks, giving Horace, in his Satires, the phrase, to behave like a Greek. Tacitus, in Germania, describing German geography and customs, condemns the drunkenness. But with all these writings providing an education against evil, the like is rarely seen at Lübeck weddings these days. Civic obedience is the watchword.

As rulers of the state, mindful of Tacitus, you combine reason, legal sanction and a due fear for the consequences of transgression. Over-indulgence is restricted through the encouragement of debate on a variety of subjects, both serious and entertaining. Through your own generosity and dignity you influence your guests’ behaviour. This is not about solemnity. We look to the example of Agathon in the Symposium of Plato; of Xenophon’s description of Callias; the noble Roman Laurentios discussed by Athenaeus in Feast Wisdom; Pliny the Elder as cited by his nephew. Perhaps I am at one of Plutarch’s dinners, as described in Table Talk: the pleasures of the debate will stay with me tomorrow. Timotheus, son of Conon, the most celebrated Athenian leader, bore witness, Those who dined with Plato felt wonderful the next day.

Ariston says much the same, referring to Plutarch and Table Talk: The academician Polemo told those about to feast, they should consider with each glass, not just the pleasures of the moment, but of its consequences. The above authors considered it appropriate, at these banquets, to write down the speeches which accompanied the wine. Aristotle, Epicurus and others did the same. Ariston made sure he shared his banquets with the erudite. And the ancient Romans, seeing friends reclining together at feasts, called it con-vivial because it held those lives together. Cicero says it was even more true of the Romans than the Greeks, that they made no distinction between drinking party, supper, symposium or dinner. What they sought was something which brought together a little of each.

In entrusting this commentary on the glories of the herring to print, I just wish to place its virtues on record. May the following chapters bring you delight whether you were there at the feast or not. In writing them down, I am refreshing my memory of a most agreeable discussion, one which accorded with Plutarch’s stipulations in every respect. I mean no insult to Doctor Grakius: he is a man dear to me in every other respect. He spoke of the herring as his own stomach experienced it: no accusations should be levelled against him. He is a man, skilled in law and zealous in pursuit of his arguments.

So, Gentle Reader, I beg you not to dismiss Of Herrings. It is my defence of the fish against the accusations he made. It has found some popularity. Please do not condemn it in advance through any tenderness in your own stomach. As Pliny says: Nothing in the contemplation of nature should be beneath our concern.

CHAPTER II

In which it is demonstrated that the Herring was unknown to both Greek and Roman writers alike

Principal among the questions to be investigated is whether the herring was a fish known to classical authority. I have my doubts. It is not mentioned in the works of Aristotle, Athenaeus, Oppian, Aelian, Pliny, Galen, Oribasius, Isaac Israeli, Ibn Sina or al-Razi, the leading writers upon matters related to fish. It may have been entirely unknown to them. In previous centuries, because of ‘the dangers of an awful and unknown sea’ (Tacitus, Germania),there was considerably less trade than we see now in these days of global circumnavigation. Perhaps time has destroyed the works of those who may have concerned themselves with this territory.

Gaul, Flanders, Batavia and Britain itself, conquered by Julius Caesar, were, of course, brought into the Roman Empire: the noblest of fishes will not have been unknown, neither to its soldiers, nor to their commanders. Salting herrings in those parts, however, is believed to have been unknown, a practice introduced from distant lands more recently. Then again, the travellers in those times were so concerned with the acquisition of wealth, why would they bother with the knowledge one discovers in books? As Petronius says in Satyricon:

If a region of the world promised gold,

It was considered hostile and ignorant, the pursuit of wealth

Justifying the calamities of war.

The literary arts and their rewards came later to these places, long remaining unknown. This is why so many of our ancestors’ outstanding achievements are lost in oblivion. But what sort of place was this Germany, described by Pomponius Mela, Julius Solinus, Strabo, Pliny (if only the twenty books of his The German War Waged by Drusus had survived!) and Tacitus’ single book? With all due respect to these great writers, Germania has altered greatly for the better. It is unrecognisable from those descriptions of its origins. Strabo himself says the country beyond the Albis and towards the Great Ocean was completely unknown to the Romans. Pliny makes clear that Germany was not thoroughly explored. It’s hardly surprising this noble native of our seas, the herring, escaped the attention of the Greeks, whose trading voyages were even earlier, as well as the Romans.

Pliny admits the existence of over 176 unknown sea fish. Their names hadn’t reached him, because they spent their lives in the vast seas towards the Indies or towards the North Pole. Complete knowledge of all fish wasn’t granted to previous centuries, hasn’t been achieved in our own and is unlikely for many to come, if ever. Byerinus in About Matters of Dining said as much. In pursuit of nature’s secrets we come in the end to the power of the Divine, from which all human thought turns away, uncomprehending.

I’m saying this in the knowledge of no reliable report that herring has been seen or recently eaten by anyone travelling to the Mediterranean or Thrace. Let me be clear: the herring was unknown to the ancients. In De la Nature et Diversité des Poissons, Bellonius says herrings are native to the Mediterranean and he saw them for sale at the market in Rome, but I’m afraid I agree with Rondelet and Ulisse Aldrovandi: he’s been deceived by the similarity of Thracian and Sardinian fish.

Both these authors make clear the herring is not a Mediterranean native, although we know the herring’s richly salted and exotic delights have been traded by the Dutch in Italy for many years. Both the celebrated Amsterdam Doctor, Franciscus Vicquius, and the noble Dr Tulp, having travelled extensively in Turkey, are uncertain as to whether they ate herrings or Cellerini in the Propontis. Bellonius thinks these were sardines or sardellas. If herring catches were on the same scale then as they are now towards the British coast of the German Ocean, it is hard to believe the herring would have escaped the Romans’ notice. Swimming at the edge of empire and beyond, the greater part of the world turned its back on the King of Fishes.

Fish live within their own prescribed borders, as if separated by walls, ramparts or hedges; as if circumscribed by lines drawn with a Thalassometer.(‘We have heard of Geometers, why not Thalassometers,’ asks St Ambrose). Each sea does not feed every fish. Each sea, indeed, has its own fish, which you’ll not find anywhere else, as was said, famously, by St Basil and St Ambrose.

Man’s intemperance is striking, considering how happy we can be in moderation; how rich we may feel in so many small ways. Nevertheless we violate age-old borders, dividing the world by fire and sword. We venture upon the sea in winter. We delve in the bowels of the Earth to the very Land of the Dead; we climb inaccessible mountain ridges to differentiate a thousand types of stone and reach the very clouds. We wander through deserts and among volcanoes on journeys of almost unimaginable length. There is no place left in the entire world unmarked by human footprints, ‘through the insatiable desire for possession alone,’ as Pliny says.

So let’s consider in which genus the Herring should be counted.

It is not a Thrissa or, in any way, of the genus Thrissae, nor is it thought to be by Caspar Hofmann, Hadrianus Junius and Rondelet, all men of outstanding learning. Thrissa is counted as a fish of the Nile by Athenaeus; as one which moves between the sea and the river by Oribasius. Dorion, in Athenaeus, describes Thrissa as a river fish, thorny, dry and without succulence. Such an insult to the herring would be inexcusable: it’s a splendid, well-flavoured fish. (Anyone wanting notes on salting Thrissa will find them in Galen, although the drier Thrissae should not be preserved in brine.)

The bellies of the Thrissa or the Alosa are protected by much sharper bones than those of the herring. Even only mildly cured, a herring’s guts come out easily. Its bones are softer and less troublesome when eating. Those of the former are more irritating, according Rondelet’s On Fish. He also distinguishes herrings from the Thrattae and the Alosae by the small round spots of the latter, remarking that in Rome, Marseilles and Venice these are so like herrings and sardines, even the Gauls, who know the herring well, accept them as such without a word.

Aldrovandi declares Bellonius was deceived by the similarity of shape: these are fish native to the Mediterranean, he argues, reporting seeing them himself in the market at Rome. Furthermore, Athenaeus says that Thrissae have not changed their home from that accorded them by Aristotle. Such ‘herrings’ would not be found by the ocean’s travellers, even if they circumnavigated the entire coast of Britain, as described in Camden, Martin Schoock and others.

This same Athenaeus describes how, in Aristotle’s On the History of Animals and Living Things, the Thrissa is called Orchestris, because it rejoices in singing and dancing and may apparently leap out of the sea. On the same point, Aemilianus (About Animals) refers to Egyptian Thrissae being caught while jumping to the sound of singing and clapping. Such behaviour is unknown amongst herrings, which assemble of their own accord in shoals beyond computation.

So: if we happen to see fish jumping and playing under a calm sky to the accompaniment of song, these are Thrissae, Italian Alosae or, if you prefer, Trichides or Trichiae (referred to by our own countrymen as Red Eyes, Blener and Blicker). In the commentary on Aristophanes’ Acharnians and in Julius Pollux these are are described as Hairy Fish, because they have bones like hair. Casaubon warns, in his notes on Athenaeus, that due to the bristliness of the bones these can cause people to choke if swallowed incautiously.

Neither is the herring Aristotle’s Chalcis, which Theodorus Gaza translates as the bronze fish, because of its scales and their silver and iron sheen. This ‘herring’ is suggested by Ulysses Aldocandusin, Camden, Bellonius and by Schoock in Belgian Treaties. Aristotle, however, says the Chalcis is a river fish. He also describes how the Chalcis can be infested with a dreadful disease and that many are destroyed by lice growing under the gills, a thing which does not occur in the fish with which we are concerned.

The true herring has silver scales, the colour of the shiniest iron. It may fully deserve the splendid name of Chalcis, but it’s not a river fish, nor, in its nobility, is it destroyed by infestation – it has never been found with lice upon it. The Chalcis spawns three times a year, according to Pliny, whereas the herring spawns only once. This is a fact. In some parts this occurs in the autumn: it expends its love, the sperm-bearing tubes become feeble, the fish is worn out and is called Spent.

The Herring is not Aristotle’s Mainis, Pliny’s Maena of Pliny, the Menola of the Italians, the Mainis or the Leukomainis found in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophia – even if Theodorus Gaza says these and the Halec are one and the same. Massirius, a diligent and learned man, asserts that which the Venetians call Leukomainides or Smerids is the same salt fish Pliny calls Giruli and that these are the Aringae of the Belgae – those who live between the Seine and the Rhine – but he’s not confident in this, as Hadrianus Junius says in Nomenclature.

The Herring doesn’t spawn in winter like the Maena, but in the spring, its offspring caught in estuaries in July and August. The Herring does not turn black or into any other colour when the female begins swelling with roe – Aristotle declares in winter the Maenae become white, in summer becoming blacker. Blue spots are not spread across their whole bodies and, in particular, on their heads and backs, as Rondelet describes. Their flesh does not become unpalatable when the female starts to swell, Rondelet describing them as goatish; Martial in his Epigrams writing:

The smell of an aroused goat can be compared

To that of the Gerres, the coarsely salted, useless Maenae.

From the above lines we have to accept these fish were of no value to the Romans and that fresh herrings were unknown.

The herring, also, is not born of sand and mud, as Athenaeus describes the Maenis. In Athenaeus Feast Wisdom,Numenius calls thempaltry and in On Country Matters Antiphanes calls them Hecate’s food on account of the witch goddess having the cheapest, smallest and most despicable fish for her delicacies. According to Erasmus, this is where we get the proverbial Hecate’s mud. Were these writers thinking of the herring? Taste one. I rest my case.

The herring is not the Halec, Alec or Hallex of the ancients, referred to in Priscian, Horace, Plautus’ The Pot of Gold, Numerus (if Nonius Marcellusis is to be believed), Martial and Pliny’s Natural History. Alex was a seasoning of brine, left as residue in the fish sauce known as garum, according to Pliny (of which more later). This is to say an imperfect and unstrained sediment. Plautus appears to refer to this in Poenulus: ‘Hallex is the salt, almost the lees of a man, that is, not a man, but all that is wrong with him’. In their commentaries, Taubmann and Lambinus argue that Acidalius Hallex was thought of as that effeminate part of a man which seeks other men for mates. Horace, in his Satires, distinguishes the lees from the Hallex:

I was the first to find the lees and the allec

And the pepper.

So, in fact, it might be that garum, alec and this sediment or faex are all products of the same process of fish salting. Garum was the most expensive of these, halec less so and faex the least valued of all. Halec was used at one time to season of food and it’s well known that garum was the ancients’ favoured sauce, as I have shown in my Purple Book. Halec, however, was prepared from various fish, along with oysters, sea urchins, sea nettles, lobsters and red mullet livers.

According to Pliny, with some fish species, salt may lose its savour in the throat. Referring to Pliny, Apicius, a man with an astounding appetite for every sort of luxury, suggests alec was made from the red mullet livers.

Neither is the herring the Lesser Alec of Columella, who writes about it in Rustic Matters. The Lesser Alec is described a river fish or as having the diminished growth of a riverine species. The herring is not caught in Italian waters. It is the especial fish of the German Ocean and the Baltic. It tolerates fresh or brackish waters only to limited extent, although it’s true, recently hatched, the young don’t like salt water and in summer months may be found in estuaries.

Considering its name, the Alec was clearly also salted, for als alos o means salt. Isidore of Seville notes that the Lesser Alec is a small fish suitable for liquefying brine. In Priscian, Charisius Halex is similarly described. Columella says the Lesser Alec, like the bronze fish, disintegrates in salt. Galen notes and experience tells us, very small fish do this in salt, becoming liquid, because of their soft, moist flesh.

I believe it to be because of this association with salt that Halec is used by Actor as the name for herring in his book The Nature of Things, which is, in turn, mentioned by Vincent of Beauvais in A Natural Mirror, by Olaus Magnus, in Scaliger’s Exercises, by Paolo Giovi and others. And now the usage has passed into common parlance. When herring is salted it is said to last, fit for human consumption, longer than any other fish and this is why Vincent mentions it more than once.

If, however, of the three possible genus classifications, one must be ascribed to the herring, I’d include it among the Chalcides or bronze fish, since Athenaeus writes that Chalcidae are called sardines by both Epaenatus and Aristotle. Sardines are similar to Herrings. Indeed, Bellonius even substitutes a picture of a herring for the Celerini or Greater Sardine. Due to the similarity of shape, I accept that sardines are a second species of Herring. They’re caught in the Mediterranean in large numbers and were well known to the ancients. Furthermore, the name of Chalcides, although specific to one species, is also used by Dorio in reference both to the anchovy, a fish which the people of Chalcedon call Encrasicheli,and to those which Athenaeus tells us they call Trichii.

Ancient manuscripts also refer to the Allus or Allex, which Scaliger’s Notes and Festus’ On the Meaning of Words describe as about the length of a thumb or index finger and favouring garlic sauces.

In this treatise I have decided to keep to the name Harengus, even though it was unknown in the marketplaces of Rome. It carries the authority of Ulisse Aldrovandi’s About Fish and Rondolet’s On Fish, as well as that of and other great writers on the subject of. It is a barbarian name and through its use I hereby confirm it to have been unknown to ancient writers.

Along with these and other authors, I say, herrings are not caught in the Mediterranean, where so many other species have been. It would be superfluous to attempt an etymology from the libraries of classical authority, in which, for so many centuries the fish was unknown. To our people it is Hering, to the Dutch Hareng, to the Italians Harengo and Aringa, to the English A Heryng, to the French Harang and to the Danes Sild.

CHAPTER III

Which reviews the nature of the herring and its grounds

The Herring is a fish. In form it is more beautiful than any other. It lives in shoals and follows its leader. According to Aristotle, there is no shoal without a leader. That most generous and excellent of men, the celebrated Dr Tulp, the Scabinusof Amstelreda, has sent me a picture of the great philosopher, the highest authority upon fish. I freely admit the extent to which his writings have helped me in my present task. This is why I have decided to refer to him whenever possible. I think it’s good policy to refer to Pliny in the same way: his Preface to the Emperor Vespasian is filled with both talent and modesty and I’ve learned so much from his work.

But let us put that to one side. If, through good fortune, fishermen catch the shoal’s leader, they catch with him such a huge quantity of herrings, the nets cannot hold them. Ropes sometimes have to be cut, it being impossible to lift them out of the sea for the multitude of fish the nets contain. So Ulisse Aldrovandi reports, drawing upon Albertus Magnus.

I can myself bear witness to the belief amongst our fishermen that, from time to time, herrings come to our own estuary and our own shores in vast numbers: over and above what is caught by the nets, stretched one after another to surround the shoal, they can be taken by the poor with their own hands and pots. It is not unknown to catch more than forty lasts.

It’s hard to believe, but true, in Bergen, in Norway, such enormous herring shoals can enter the harbour and gather along the neighbouring shores and rocks, if an oar is placed in the water it will stand upright. People say this happens particularly in Norway, either because the fish are driven there by storms, or because they are being chased by a whale, which can consume an enormous quantity of fish at one gulp. (Olaus Magnus, About Halex)

In mentioning the Whale, I should remind readers of how Oppian, that excellent writer on all salty creatures, celebrated it in his most charming verses on the great beasts of the sea. The whale, he writes, grows to an astonishing size, but at a distance cannot see its prey because of the huge weight of fat it carries in the hump above its eyes. If its ears become blocked or obstructed, it is not able to avoid the shallows which are dangerous to it. For this reason it travels with a companion, a small, white fish, Aemilianus adds, with a long body and a narrow tail. This fish swims closely in advance of the monster and, by moving its tail before the Whale’s eyes, indicates whether there is prey nearby, an ambush prepared by fishermen or hidden rocks, shallows and narrow places that must be avoided. This is why Oppian calls this fish a leader (Pliny calls it a sea muscle). If it is intercepted, it is easier to catch the huge monster of the depths, as it thrashes and crashes about, after the manner of a cargo boat, its helmsman lost, swamped in a particularly violent storm. I refer you to Aemilianus’ Histor. Animal.

These days, whale fishing is pursued by crews carrying three-pronged harpoons, each with very long ropes attached: they try to spear the whale between the scales. When the monsters are wounded and their blood colours the waves around them, they dive for the sea bed, but this makes the harpoons’ wounds even deeper, so that at last, drained of blood, they give up their lives. When their corpses have been brought to shore and cut up, the fat is liquefied by cooking, as it is especially useful in the workshops of tanners and others. Catching whales is very dangerous: they often capsize the boats and drown the fishermen. Each man’s harpoon is given an identifying mark, so the ones most active in the chase, the ones who penetrate the beast most deeply can be rewarded for their labours at sea.

The herring spends its life and is caught in the wide German Ocean, which spreads itself between Germany, Great Britain and Norway. In Britannia,Camden, the most famous writer on English matters, testifies that it swims around the coast of Britain in vast numbers each year:

It makes its way from the deep ocean to the shores of Scotland around the Summer Solstice. Because it is fat at this time, it is most sought after and is sold immediately. From there it heads for the shores of England, so that from the middle of August until November, when it is at its best and fattest, it is to be caught between Scarborough and the mouth of the River Thames. After this, carried onwards by the violence of storms, it presents itself to the fishermen of the British Sea right up until Christmas. From here it swims west to Ireland and up on both of that country’s coasts, going right round Britain. In June is appears to stop, then, after it has spawned, it returns in great numbers.

That most famous Dr Tulp writes:

Fishermen follow the Herring, travelling from the Orkneys or Shetland, down the coast of Scotland and England. The Herrings sink to the bottom of the sea, not far from the harbour of Yarmouth, and there, as if in the safest of refuges, they lie hidden until, with the approach of Spring, they begin their journeys afresh, directing their route along lines marked out for them by the unfathomable wisdom of God, through the narrow seas between Gaul and England, dividing themselves as necessary, so that, after completing this voyage around the whole of Britain and Ireland, they meet once again at the same place from which they set out, combining together at the end of each year and awaiting the arrival of the fishermen from Holland and Zeeland.

These fishermen make for the Ocean in large fleets and, from the Summer Solstice to 1stst December, they are busy catching herring. Having followed their leaders across so many seas, you’ll see the shoals of Herring so dense they disturb the surface of the water and the waves become slow. Nets are often torn by the sheer weight of them, as Paolo Giovi writes in his treatise On the Hebridean Islands.

Large numbers of herring are also caught off Denmark, in what is known as The Belt, as well as its islands and provinces – notably towards Scania, around Falsterbo. (Retaining its ancient name of Scandia or Scanzia, these shores are the workshop of the world and the birthplace of nations, according to Jordanes, On Matters Concerning the Danube). The quality of these herring is not as good as those off England and Holland.

A large number of herrings are similarly caught by the people of Bergen and along the whole coast of Norway.

In our times, the herring is rarer than once it was. It is also rarer on the southern shores of the Baltic, but it is caught occasionally and the closer we are to winter, the fatter and more delicious it becomes. Around February, as Spring approaches and the West Wind blows, when creatures of the land mate and marry (with Pliny, we refer to the generative spirit of the warming world, the feminine becoming both receptive and fecund). At this same time, in an enthusiasm of love, many fish also choose to spawn – and this is testified in Aelian’s On the Nature of Animals. The herring travels across the Baltic to its southern edges, the estuaries and coastlines, so it may lay its eggs in calmer waters; such places as offer sanctuary from the violence of storms and the savagery of whales.

Anyone questioning the self-protective intelligence of fish should read Pliny and Aelian. They both describe fish which, for these same reasons, leave the Mediterranean for the Black Sea. Looking to the safety of its progeny, a fish seeks peace and quiet when spawning (see also Plutarch’s On the Cleverness of Animals). Aristotle says the same in his description of the tuna’s migration to the Black Sea, where food is all the richer for the gentler waves; where it may spawn more safely on account of the lack of whales; where it’s more convenient to give birth because the sweeter waters better nurture its offspring. Spawned and growing up, however, they head for the wider seas again. In relation to the Black Sea, Basil the Great confirms this.

As proof of this theory, which explains why there are so many varieties of fish in the inlets of Borussia and Pomerania, it seems appropriate to add this comment from Divus:

Fish from so many different bays, as if by common plan, head in the direction of the north wind in a single shoal, hurrying towards that Northern sea, as if by some natural law. If you were to see them swimming thus, you’d say it was some current carrying them, cutting through the waves in such strength into the Propontis and the Black Sea.

In all of this I discern the rays of a Divine light, which penetrates even to the bottom of the sea. Thus awakened, at the established time and in their proper ranks, fish seek certain places, as if at the command of some general or master. As the Divine, St Paul, would say, neither taught nor knowing what they have to do.

We should only be all the more ashamed of our human attempts at anticipating the shoals. St Ambrose says:

Fish cross such great seas in order that they might find some usefulness in their own kind. We also cross different seas, but how much more honest is something done out of love for future generations, than out of the lust for money! Their crossings may be considered piety, ours the pursuit of profit. To them, their offspring come first, more precious than any financial gain; the wages we bring back take no account of the dangers involved in the unhappy pursuit of gain. And so it is that they make their way back to their native land, whilst we abandon ours. They increase their own species by swimming; we diminish our own species under sail.

But back to the herring.

Good catches are made when there is cloud, rain or snow. When a gentle wind is in the South West or the South, herring can be caught by the last. In dry and calm weather, catches are smaller. When the seas rage, especially with gales from the East or the North, herrings swim down to the sea bed where it’s calmer.

Apart from the swordfish, whose scales face towards its head, fish adjust to wind strength, always swimming against the waves and the tide, careful not to show their tails to a following wind and consequently risk a painful loss of scales (Plutarch, On the Ingenuity of Animals). On the other hand, when these winds blow gently and it is cloudy or rainy, I’ve seen huge herring shoals pouring into the estuaries, along the coast and into the nets.

As the air warms and frogs begin to croak, they turn back, leaving their spawn behind and heading for the open sea. The immature fish can be caught over the next few months, until, becoming intolerant of fresher water, they themselves, swim out to sea, where they soon grow to full size. This phenomenon can be observed in other fish too (Aristotle, Basil the Great and Ambrose of Milan).

I’m of the opinion, in the depths of winter when the sea is at its wildest, herrings make for the sea bed and hide as other fish do: it’s quieter down there and warmer (Aristotle, Aelian, Pliny, Vincent of Beauvais, Olaus Magnus). Camden, in Britannia, says in the roughest northern winters, they hide in the deeps and in caves.

In the breeding season, I believe they wake and set off for more comfortable locations, spawning along the vast shores of Norway, of Scotland and neighbouring islands – northern seas being sweeter and better for feeding the fry. When drawn by Spring’s warm breezes, they head for more temperate southern climes (something other fish also do, according to Basil the Great, St Ambrose & Aelian) where, refreshed after a short period of feeding, they become such a rich catch for the fishermen.

There’s one thing which puzzles me: herrings are believed to appear once a year, around the dates I’ve indicated. On the other hand, according to reliable observation it is agreed, with Venus in the descendent, they head for Scania every autumn, whilst in September the same fish – tubes empty, where there’d once been milky sperm and eggs – are known to reach Dogger Bank near the coast of England. Weak and dry, these herrings are only suitable for the lower classes. The Dutch call them Edel Hareng, whereas we call them as Spents. So perhaps, contrary to our previous assertion that they produce offspring only once a year, herrings spawn twice.

We must defend the truth here: these fish come just once a year, every year, under the influence of Venus. In early spring, in the northern fisheries, most herrings are certainly thin, weakened by mating and then giving birth, suitable only for bait; some may come up from the sea bed later, but it is logical that those coming out of their hiding places most recently should be plumper – as Aristotle says, they will be the most fertile after their long rest. This is why the Dutch and their allies ban fishing for the salt herring trade before St John’s Day, June 24th, when these same herrings are at their best – young and only moderately full.

There are among them, however, some really full ones, swollen with eggs and sperm. Not as sweet as the others, these are put in differently branded barrels, as suitable for alternative household uses. It seems likely these spawn later in the autumn on the sands of Dogger Bank. There are fewer of them compared to the earlier spawners, but there are tasty ones among them, ones perhaps that failed to mate in the autumn – although it can be hard to identify these from the ones already making their way towards their winter quarters.

Should we put this down to distinctive qualities in the herrings or to the nature of the different locations? Do the certain forces that urge conception on land (Pliny) exist in the same way at sea? Clarissimus the Interpreter argues fish may spend their time in the same places but breed and migrate at different times; that their secret ways are determined by Proteus or Nereus and are therefore unfathomable. Athenaeus, on the other hand, says he is simply misinterpreting Aristotle.

Scaliger suggests two species of herring, a very small one, known in North East Italy as Anchoia genuensis, and a larger one, which appears to be the sardine. I’m not able to make a precise and scientific determination as to herring types and characteristics – the fish are spread too widely – but I’d suggest three. Firstly, there is the Greater, which wanders around the German Ocean and is rightly and properly called The Herring. This may vary in size to such an extent that those caught in Scotland or Norway can be twice the size of those in Flanders – although irritatingly this is not always the case and sometimes they are not.

Secondly, there is the Smaller, which tastes roughly the same, but is a little fatter and very suitable for steaming. It can be caught and confused with The Herring. It is like them, but a little broader in the body and a little less rough about the belly in the way its scales stick out. We call these Brisling; in the Mediterranean they’re called sardines; the English, if memory serves, call them sprots. According to both Joh. Isacius Pantanus and Bellonius, the English ‘sprot’ is the young or offspring of The Herring. As said, however, where he’s been describing Sardina and Celerini, he’s used a picture of our own herring: this is how he manages to class Gesueris Sardina among its kind.

The third type, The Swedish, is intermediate in size between the other two. It is known as The Swedish, but also called Halec Bothnicus by Olaus Magnus and Stromling by the common people. The Swedes catch it in great numbers – certainly enough for the Arctic kingdom of the Gulf of Bothnia – and it is widespread throughout the Bothnian Sea.

In Sweden, Finland and Estonia – all those lands ruled by Christina, most serene and powerful Queen of Sweden, a ruler unmatched in any age and known to the whole world for a brightness of virtue such as cynical posterity will scarcely believe – The Herring is not found, but The Swedish or The Stromling compensates for its absence. It is a fish highly recommended by doctors, if eaten fresh and mature, its pale flesh tender and soft, but drier and more fragile than that of The Herring. As Columell suggests, like rock fishes, we call it after the rocks amongst which they live.

Salted they are a little bland, not as good as The Herring, indeed a bit like rock fish, which Galen considered unsuited for salting. Soft or very dry fish, lacking in oil, may be unsuitable for salting: since salting draws any liquid from the flesh, a dry fish becomes leathery and those which fall apart when steamed tend to melt when salted (Galen, Isaac Israeli).

The idea that stromlings are barren and lacking in entrails, as Olaus Magnus says, is not true. He says the same of The Herring and any one who has recently gutted one can confirm that I’m speaking the truth.

The shrew may not signal its presence, but the herring bears witness to the shoal. Its eyes and scales shine at night, making the surrounding sea flash with a fiery brightness. Moving back and forth the shoal seems to kindle lightning. We call this Herringflash. This bright reflection in the eyes lasts several days after they are dead.

If we are to believe Solinus, something of this nature is found in the birds of the Hercynian Forest – Their feathers shine and glisten in the dark, though the pall of night may make the darkness deeper. And Pliny says of the species of shellfish known, because they look like nails, as Dactyli:

It is in their nature to shine in the dark, when the splendour of the day has been extinguished, and the juicier they are the more they glow in the mouths of those who eat them and on their hands, on the ground and on their clothes, wherever the juice may drip.

The seagulls which the Netherlanders call Jan van Sent and which we call Memen, also have a reputation of giving away the position of herring shoals: having seen them on the surface, they flock to eat the spoils. Dr Tulp reports that the silver gleam of herrings on the surface shines more at night when there are more accompanying shoals below. In order to catch these, fishermen now lower their nets up to seventy feet deeper.

Dr Nicolaes Tulp has also reminded me in a letter, that sailors say the sea monster, known by then as Hille and called Helius by Olaus Magnus, does not like to see herring caught in the nets. It will strike the side of the ship like a hammer and, when the sailors raise their nets, it seems the monster has the fish and they do not.

Vincent of Beauvais describes this, seemingly drawing on the same source. Olaus Magnus and Ulisse Aldrovandi both declare that whenever they see a light shining from above on to the surface of the water, the herring shoals will swim up, enticed into the nets at certain times by this trick, as if they are happy to be caught as a gift from God for the good of mankind. This trick, however, is no longer deployed in Scandinavia or on our own shores, not making any sense to our fishermen, who hold rather that it frightens the herring and that the fish, in fact, hide from the brightness of snow or of lightning.

Dr Tulp also reports this method as having also been discontinued among the Dutch. Such fires as they kindle in the dead of night are used to let other boats know, that they’re about to haul up their nets because the sea is getting rougher; that their comrades need to take care none of their nets are likely to get snagged in the process. Trout and crabs, I remember, are supposed to be deceived by nocturnal lights.

Herrings do not tolerate fresh water and will soon die if placed in any – unless you add salt and even then they do not last long. I have, however, seen them live for more than an hour, packed closely with other herrings and transported in winter. Gessner, in his Book About Fish, thinks the opposite, that herrings cannot live out of water at all, dying immediately as soon as they feel the air: that there is no delay between the touch of air and death. This is also said by Vincent of Beauvais, Ulisse Aldrovandi and Olaus Magnus.

As I write, the memory of a fish comes to mind: Pomeranian nobles call it the Muraena, but is more correctly called the Lake Herring. It is unrelated, or only slightly related to the Muraena of the ancients through its similarity to the herring. It has a pleasant taste and a tender flesh. In fact, only its habitat, generally lakes and ponds, leads to suspicion as to its virtues. At first sight you’d think it a herring, but it is more scaly, there’s a line running along the length of its body, it is smaller and its flesh is heavier.

My friend Gottfried Acidalius, however, reports that in Marchia they grow to the same size as the herring and are seasoned with salt. He is a man of great elegance and enormous learning and has given me one of these Muraena from the fish tanks of his Most Illustrious Lord, Jochim Ernest, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, its civil and military prince. It is said these fish squeak and die quickly in the same way as the herring.

CHAPTER IV

Concerning the squeaking of herrings whilst they do not breathe

It’s well known, fish do not have voices. From this comes the saying, more silent than a fish. In Ajax the Whip-Bearer Sophocles calls fish mute:

He brought destruction to mute fish,

He brought a plague upon the mute fish.

According to Athenaeus, fish are said to be mute by the poets, because, like mutes, they lack voices. The word derives from the Greek words for to shrink, to be done and voice. Fish have no lungs, no windpipe, no throat: the organs used in voice production. For this reason, although they ate other living things in moderation, even sacrificed some, the Pythagoreans would not eat fish. They revered silence, considering it a divine quality (Athenaeus). There is more on this in Plutarch, where it’s said Pythagoras bought a catch of fish and ordered that they be set free.

Aristotle observes that some fish make hissing sounds. Lyra and Chrome Fish make a grunting noise. The Boar Fish of the River Achelous is thought to have a voice and as to the Erica and the Cuculus, one produces a kind of whistle, the other a noise like the cuckoo’s song – from which it gets its name. Aelian confirms this. And so those who condemn all fish to mute silence may not have read the texts. Exocaetus, a fish which sleeps on the shore by the Arcadian town of Clitorium, is said to have a voice and, a thing of even greater wonder, to have no gills.

Herring, taken from the net and thrown into the boat or pressed in the hand, whistles – something our Mytuli,as well as the Lake Herring or false Muraena,are also heard to do when taken out of water.

All fish have this so-called voice, coming either from their gills, which contain little bristles, or from the innards gathered around their stomachs. Air is held in these places and, when the fish are rubbed or shaken, sounds are squeezed out. The sound is the air being drained from the innards. This principle also applies to insects, such as bees, flies and the rest, which buzz because, when they fly, they are expanding and contracting. Cicadas appear to sing because of the air being pushed out when they shake the membranes beneath the thorax. It is a distinguishing feature and Aristotle has more on the subject.

The herring, taken out of water, wriggles and, deprived of its natural element, soon dies due to the forceful rending of its gills. Eels on the other hand, along with the Muraena and other snakelike fish, are able to live longer away from water, because their small gills need less moisture – see Theophrastus’ On Fish that Live on Dry Land. Athenaus confirms it. All these arguments allow us to be certain that fish do not breathe because they lack lungs and that they die when exposed to fresh air.

Aristotle, in On Breathing, widely taught exactly this, contradicting Democritus, Anaxagoras and Diogenes the Cynic, all of whom reported that fish breathe (see Pliny). Various unconvincing arguments are presented: the panting or gentle gaping of a fish’s mouth in the heat of summer; the bubbles rising through water seen as the breath of life as experienced on land; the ability to hear and smell, both faculties dependent on the material of the air; the assertion that nowhere is without the gentle breathing of sleep.

Fish do not tolerate extreme cold, hiding in caves in a freezing winter (Aristotle, Aelian and Pliny), relaxing and swimming towards the surface in warm water, where the temperature is the same as their own. On the other hand, if it’s too warm and, unable to bear the temperature, they need to cool down, they hide in the depths where the air cannot reach in the way it does at the surface. The bubbles, in fact, rise due to the water, taken in with food or otherwise, being expelled from the gills (Aristotle).

The ability of fish to smell and hear suggests the penetration of air into water, as air would be necessary for this to occur, but the question of breathing is not affected: we all know, both water and air cannot be taken in simultaneously (Theophrastus). It’s also the case that sleep doesn’t require breathing in a fish. Hysterical women have been known to live for several days without any sign of breathing, sleep reviving them; fish revive themselves through the gentlest motion of their gills, as if their hearts had been moistened with dew.

Galen agrees, arguing even that fish are so cold by nature, their hearts do not require deep breathing. He argues this from their low blood content, warm-blooded aquatic creatures such as dolphins, seals and whales being said to breathe as land animals do. On the other hand, he writes that their gills are capable of receiving both air and vapour through a number of small openings which are so fine, they reject the larger molecules of water.

Along with Basil the Great and Ambrose of Milan, I believe water, their natural element, fulfils the same function in fish as air fulfils for land animals: after all, on land we see them die in the midst of the air. As the lung, loose in texture and full of holes, through its expansion and contraction drains and returns air for the heart, so gills open and close, drawing water in and out whilst simultaneously cooling the heart. As is demonstrated by Galen, the structure of the gills in fish is equivalent to that of the lungs (cf. Aristotle’s On Breathing, Ambrose of Milan’s Hexameron and Basil the Great’s Hexameron).

Certain fish, I grant you, play it both ways, being dual-natured. This is not in relation to their feeding habits, but because they drain water and air through the same structures – although not at the same time. Theophrastus writes about the Exocaetus, which emerges from the sea to sleep; Pliny, Clearchus and Athenaus say the same of Indian fish which climb out of rivers and jump back, as well as of a type of fish in the waters of Babylon, which remain in caves when floods subside.

According to Theophrastus and Pliny, They come out in search of food, moving by means of small fins and quick flicks of their tails, returning to their caves when faced with predators. Their heads are like sea-frogs, their other parts like those of the gudgeon, their gills like any other fish. Theophrastus says they are fish of a different nature. Requiring moderately low temperatures they have small gills, preventing any rush in the intake of air. This is also seen with the Muraena, with eels and with other fish said to spend longer periods on dry land.

CHAPTER V

In which it is shown that herrings do not live on seawater alone

It would be superfluous here to add an illustration of a herring and to describe its appearance in detail. Many famous authors have already done this – in particular, Albertus Magnus, Olaus Magnus, Conrad Gessner and Deodatus (On Health).

The herring has no intestinal complications, just a straight tube which is always empty, as if it immediately voids itself of food once it has been taken in. Evidence of this persuaded the author of On Matters of Nature (cited by Vincent of Beauvais in On the Mirror of Nature, by Aldrovandi and by Rondolet writing on the subject of herrings in About Fish) in his belief that herrings eat no food, being content simply with seawater – after the manner of Apuas that are born out of sea foam. Fishing writers declare them to be kept alive by seawater, their excellence stemming from the way they live upon this single pure element. From this Vincent states: the herring is said to live on the pure element water in the same way that the salamander lives on fire.

Opposing their opinion, one could argue that there’s no power in a single element capable of generating or nourishing life; also that there is no water so pure it does not have some earth mixed with it. And seawater contains salt. It is heavier than fresh water, is complex and is mixed with many other substances that combine in that salt.

In his Meteorology Aristotle says the density of water can produce such differences as make cargo vessels almost sink in rivers with the same weight that at sea makes them only moderately laden and perfectly fit to sail. Pliny declares seawater, heavier by nature, can withstand heavier loads. I would say, as is widely known, there are many more kinds of living creature in the sea, where it is more fertile, than on land. It is reasonable to hold to the Roman opinion (Pliny), that whatever exists in any other part of nature also exists in the sea – where you also find things which do not exist elsewhere. This is why poets present Venus as born of the sea an, why they make sea gods fertile and the parents of many children (Plutarch).

The sea owes a gratitude to the salt with which it is suffused, even to its depths. The sharpness of it awakens lazy Venus with its tickling. In men, nature locates one of the vessels for generating sperm next to the left kidney, so it can drain away sourness and the irritations of sexual desire, which like a bitterness under the skin creates an itch (Nemesius Philosophus).

The sea indeed draws fertility from above, from the fruitful skies and rains. Pliny and Aristotle declare rain to be good for fish, with one or two exceptions. I would argue that wind does not further increase the sea’s fertility.

Since fresh water draws in the strength of such grasses as grown in it, would it be surprising to find that the sea, which has much salt dissolved in it, also draws strength from the plants and grasses which grow in it, and in as much profusion as we see on land – and that this might be sufficient to feed some kinds of fish. The strength of earth alone is enough to nourish such as Thrissae, Cyprini, etc., which live just on mud and get fat in fish ponds where there are hardly any grasses. How can we therefore deprive the sea, with all that it holds, of the capacity to nourish?

This doesn’t contradict Theophrastus in saying the sea is ‘without food’ (On the Reasons for Plants): he’s describing land-based plants, which need to be irrigated with fresh water irrigation (Pliny). What of the many trees or plants nourished beneath the waves? Undoubtedly, fresh water is contained within the sea: Aristotle (Meteororology) has demonstrated that it can be filtered out by means of wax vessels. Aelian has also argued that fish are nourished by the sea, agreeing with Aristotle, Democritus, Theophrastus and Empedocles. Pliny meanwhile identifies particular benefits to be found in salt water, which helps to bring out the sweetness in and improve the fertility of radishes, beet and cunilae.

Pliny and Theophrastus both write that palms and gum trees grow in salt water. Theophrastus adds that certain plants are better nourished in it: with palms some measure of salt is advantageous and some herbs and vegetables – cabbages, rue, colewort – turn out better for being irrigated with salt water. This same argument is found in Androsthenes’ account of Tylum, an island in the Red Sea unusual for its running salt water, which nourishes trees and other kinds of plant more than rain water: so much so that immediately after rains, its farmers direct the streams away from their fields.

These and other plausible arguments for the sea’s nourishing powers could easily account on their own for the herring’s food, were it not that it has innards just like other fish, the intestine being held mostly in its upper parts, curving in to a point around which many blood vessels are joined. And it is not always empty, but often filled with food. I have often counted more than sixty tiny fragments of sea onion in one fish, many already in the process of being digested. I have not found their intestines to be swollen in this way after spawning, but rather half full of roe – that of other fish or their own – sometimes flowing with the white juices of fertility.

For this reason, along with Aristotle writing on egg-laying fish, I believe herrings are savage towards their children, especially when, exhausted by making love, they find harder food difficult. For at the time of spawning (the words are those of this most valued author), the females follow the males and eat their seed, striking the belly with their noses, encouraging them to deposit their seed more quickly and in greater quantity. At the time of birth, the males follow the females, eating the eggs they lay with their teeth, the succeeding generation of fish emerging from those that remain.