The great American modernist, his poem, ‘Fish’ and his form with herring imagery

WILLIAMS, WILLIAM CARLOS: FISH

Modernism may not have done a lot for herring poetry, but William Carlos Williams (1883 – 1963) did his bit. In Fish (1922), other species get more than a look in, but herrings get the first five stanzas – even though he cut one of them later.

Most famous for Paterson, which he wrote between 1946 and 1958, Williams’ was a major influence on the generation of beat poets that was emerging at that time. Beyond the riches of his own work, he was a force in the democratising voice of American poetry.

Influenced, himself, by Ezra Pound, he became part of the Imagist movement and, like Pound, he took his own route out of its limitations. Pound and TS Eliot went to Europe, Williams largely stayed home, working as a doctor in Rutherford, New Jersey. He listened to people while he was out and about and wrote in his spare time – drawing on the voices and the stories that surrounded him.

He had difficulties with Eliot’s The Wasteland and the impact it made, when it was published in 1922. He wouldn’t have been human if he hadn’t felt a bit miffed at the way it so rapidly became the key work in English language modernist poetry. But, in playing for the academic response (and exegesis), he resented the way it took the modernist project away from the more everyday furrow he was ploughing.

Eliot was already going off in the 30s, though. Poetically, The Four Quartets (1940 – 42) were really his last hurrah. Williams, on the other hand, was just getting going. When I think of American poetry it’s the direct, plain speaking quality you find in Williams (and others) to which I’m always drawn.

Broom

Fish originated in a story told by Carolina Benson, an old friend of the family, in Vermont in the summer of 1921 (according to Williams’ friend John C Thirlwall). It’s a set of fish-based memories from Benson’s early years in Norway, specifically, though not necessarily exclusively, in the Lofoten Islands.

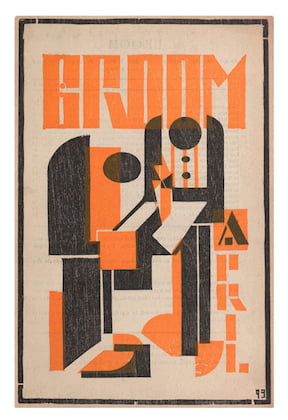

It first appeared eight months before The Wasteland in the extraordinary magazine Broom. Between 1921 and 1924 there were 21 issues of Broom. Along with more from Williams, it published work by Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, ee cummings, Marianne Moore, Gertrude Stein, Haniel Long, Virginia Woolf and John Dos Passos.

There were translations of Pirandello, Eluard, Aragon, Appollinaire… For God’s sake, the cover designers included Fernand Léger, László Moholy-Nagy and El Lissitzky. It’s enough to make you weep. It closed, like so many literary magazines, due to lack of funds – which may offer a crumb of comfort to today’s poetry editors. Princeton University has digitised all the issues as part of its Blue Mountain Project (see link below).

Fish appeared in April 1922. The issue’s cover design is not credited, but the closest in look are the woodcuts by Léger (January and June ’22) and Ladislaw Medgyes (June ’22).

Williams and Herring

Carolina Benson’s story sparked the poetic response, but Williams already had form with the herring. His father being English, sadly, the odds are against it having come from him. His Puerto Rican mother, however, had a family background that mixed Spanish and Portuguese (fish lovers), Dutch and Jewish (herring obsessives).

It would, of course, be academically reprehensible here, not to acknowledge that New Jersey has its own herring fishery and that Williams might have been a first generation herring enthusiast.

In For Viola: De Gustibus (1912) considering the taste of his Belovéd (caviar, Japanese bird nest, quince), both the pimento and the herring fall short:

No herring from Norway

Can touch you for flavour. Nay

Pimento itself

Is flat as an empty shell

When compared to your piquancy…

The association of fish with sex and both male and female sexual organs is longstanding (see Fasting). The association of herrings with Norway, which may also have resonated with Carolina Benson’s story, is interesting.

Pound had introduced him to Viola Baxter five years earlier. She offered a New York sophistication that required the stakes to be raised. In considering or imagining her flavours (he married his wife, Florence Herman – Flossie – in 1912) he reaches beyond the commonly available options, but herring clearly remains a sexually-resonant taste option.

In 1912, Britain was unquestionably the top exporter of salt herring, but there may have been a brand of Norwegian pickled herring of which he, Viola Baxter and/or Florence Herman was particularly fond. It was, of course, 1912 and The Great Sardine Litigation, in which the French opposed the labelling of Norwegian, fjord-caught, young sprats and herring as sardines, was not yet resolved (see Canning).

The sexual resonance recurs in the prose poem, The Delicacies (first published in The Egoist in 1917 and then in the collection, Sour Grapes, 1921). Williams describes the piece as: an impression of beautiful food at a party, image after image piled up, an impression in rhythmic prose. But the dishes are juxtaposed with sketches of the hosts and guests, the poet’s eye lighting with favour on the hostess, her younger sister and then his wife, whose prettiness (when she cares to be) is somehow enhanced by her interest in a conversation on Day Nursery provision.

It’s witty and self-satirical. Juxtaposed with his hostess, We began with a herring salad: delicately flavored saltiness in scallops of lettuce leaves.

The Third Stanza

For his collected editions, as well as handful of minor tweaks, Williams cut the third stanza from Fish:

Men call from the cliffs

or blow horns

that the fishermen

shall go down to the shore

to their boats and nets

to make the catch.

It’s a beautiful detail if you’re interested in herring fishing traditions: an exploitation of the specific context offered by the fjord for looking down on signs of the shoal in the water. It’s obviously much harder to spot these at boat level.

Maybe it distracted from the later appearances of cod, sardines, mackerel, anchovies, trout, salmon and kingflounders; from both the land-based Norwegian siren, the huldra, and the male shape-shifting, banshee-like nekke (nøkken in Norwegian). Maybe the men on the cliffs distracted from the focus on the water and the shore of the fjord.

The image of young Carolina in the boat is suggestive of C12th / C13th Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus’ description: There are so many fish in the Sound that the ships can hardly use their rudders and one can catch them with the hand alone, without the use of any instrument (see Skåne Fishery). There is a rich fecundity in it and a sense of the association Williams made between herrings and women. Maybe the men on the cliff distracted from that.

Anyway, the text of the poem, here, is taken from the excellently annotated Collected Poems Volume 1: 1909 – 1939, published in 1986. I am very grateful to New Directions for allowing me to reproduce it here.

FISH

William Carlos Williams

It is the whales that drive

the small fish into the fiords.

I have seen forty or fifty

of them in the water at one time.

I have been in a little boat

when the water was boiling

on all sides of us

from them swimming underneath.

The noise of the herring

can be heard nearly a mile.

So thick in the water, they are,

you can’t dip the oars in.

All silver!

And all those millions of fish

must be taken, each one, by hand.

The women and children

pull out a little piece

under the throat with their fingers

so that the brine gets inside.

I have seen thousands of barrels

packed with the fish on the shore.

In winter they set the gill-nets

for the cod. Hundreds of them

are caught each night.

In the morning the men

pull in the nets and fish

altogether into the boats.

Cod so big — I have seen —

that when a man held one up

above his head

the tail swept the ground.

Sardines, mackerel, anchovies

all of these. And in the rivers

trout and salmon. I have seen

a net set at the foot of a falls

and in the morning sixty trout in it.

But I guess there are not

such fish in Norway nowadays.

On the Lofoten Islands —

till I was twelve.

Not a tree or a shrub on them.

But in summer

with the sun never gone

the grass is higher than here.

The sun circles the horizon.

Between twelve and one at night

it is very low, near the sea,

to the north. Then

it rises a little, slowly,

till midday, then down again

and so for three months, getting

higher at first, then lower,

until it disappears —

In winter the snow is often

as deep as the ceiling of this room.

If you go there you will see

many Englishmen

near the falls and on the bridges

fishing, fishing.

They will stand there for hours

to catch the fish.

Near the shore

where the water is twenty feet or so

you can see the kingflounders

on the sand. They have

red spots on the side. Men come

in boats and stick them

with long pointed poles.

Have you seen how the Swedes drink tea ?

So, in the saucer. They blow it

and turn it this way and that: so.

Tall, gaunt

great drooping nose, eyes dark circled,

the voice slow and smiling:

I have seen boys stand

where the stream is narrow

a foot each side on two rocks

and grip the trout as they pass through.

They have a special way to hold them,

in the gills, so. The long

fingers arched like grapplehooks.

Then the impatient silence

while a little man said:

The English are great sportsmen.

At the winter resorts

where I stayed

they were always the first up

in the morning, the first

on with the skis.

I once saw a young Englishman

worth seventy million pounds —-

You do not know the north.

— and you will see perhaps the huldra

with long tails

and all blue, from the night,

and the nekke, half man and half fish.

When they see one of them

they know some boat will be lost.

Fish by William Carlos Williams, from THE COLLECTED POEMS: VOLUME I, 1909-1939, copyright ©1938 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

See also

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BRITTEN

- DRIFTERS (DOCUMENTARY FILM)

- DUTCH GRAND FISHERY

- EYVIND SKÁLDASPILLIR

- FASTING

- HARENG SAUR

- HERRING LASSES

- ICELANDIC FISHERY

- IDDIKETTS OR IDDIS

- JEWISH RECIPES

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- MARTYRED SAINT

- MONKEY BUSINESS

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- RING NET: WILL MACLEAN

- ROLLMOPS & BISMARCKS

- SARDINES

- SCHMALTZ HERRING

- SHOALS

- SHOALS OF HERRING, THE

- SINGING THE FISHING

- SWIFT, JONATHAN

- WHITE HERRING