An interview with Scottish artist Will Maclean on his documentary exhibition, The Ring Net, which he developed between 1973 and 1978

RING NET: WILL MACLEAN

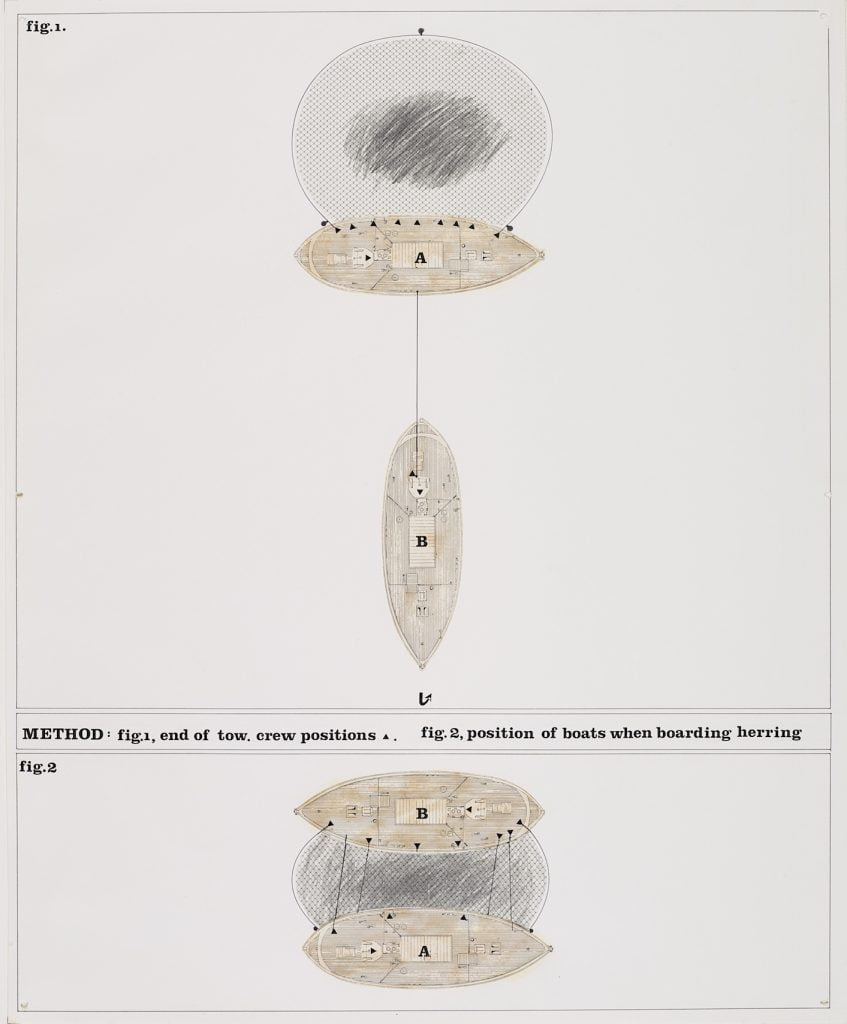

Between 1973 and 1978 Scottish visual artist Will Maclean developed The Ring Net, a detailed documentation of a method of herring fishing, largely conducted by two boats working together. The ring net method originated in Loch Fyne in the 1830s and, although resisted by drift netters, spread extensively on the West Coast of Scotland, on the North Sea Coast and elsewhere, coming to an end with the wide scale adoption of purse seining, pelagic trawling and the herring population collapses of the 1970s. The documentation, which was developed alongside that of Angus Martin, who wrote The Ring Net Fishermen (1981), is focused on Loch Fyne and on Skye, with whose fishermen Maclean was more personally connected.

(collage – paper and adhesive plastic – pencil and pen and ink on glazed Kent paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

A list of works from Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre, where The Ring Net was first exhibited in January 1978, includes over 250 photographs, nearly 70 drawings and well over 30 prints and tracings. The originality and artistic significance it holds as a body of work finds its focus in the drawings. The exhibition is held by Scotland’s National Gallery of Contemporary Art, which is in the process of making the work available online.

The herripedia is as drawn to documentary as major documentary projects have, over the years, been drawn to the herring (Hill & Adamson’s The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth; Grierson’s The Drifters; Mitchison and Macintosh’s Men and Herring; Parker, McColl and Seeger’s Singing the Fishing). Full disclosure: my first paid writing gig, in the early 80s, was a documentary text, I’ve worked with a number documentary photographers and spent nearly 20 years as a member of Amber, a documentary film & photography collective. It’s fair to say it has coloured my engagement with the visual arts.

An interview with Will Maclean

Will Maclean’s study, nearly 50 years after he began work on his epic documentation, reveals a man who has kept faith with the herrings. Have you read this? he asks, pulling a copy of Donald S Murray’s Herring Tales (2015) from the shelves. Then there’s The North Herring Fishing (2001), another in the series of great books by Angus Martin. I make a note to get a copy, but then he pulls out DH Edwards’ Among the Fisher Folks of Usan and Ferryden (1921), the cover of which alone makes it an object of desire. I could have spent a week just going through Will’s book collection, his albums of herring-related postcards and much more, but I’ve come interview him about The Ring Net, starting, more-or-less, at the beginning.

My father was harbourmaster in Inverness and he was from Coigach and my mother was from Skye and although we lived in Inverness we were in a kind of West Coast bubble and my father was a native Gaelic speaker. I had nothing to do with the East Coast beyond the fact that my mother’s father was a Reid from Lossiemouth. Three of my four grandparents were native Gaelic speakers. The fourth was from one of the East Coast fishing families, but they’d came over and settled first in Portree and then in Kyleakin. They were drivers, go-ahead, typical hardworking East Coast people, but in terms of East Coast culture, I knew very, very little about it. Everything that I grew up with was from the West.

I always knew ring netting from the earliest days of my childhood, because my grandparents lived in Kyleakin and my uncle and all my cousins worked on the ring net boats there, which at that time were the varnished boats, the Castle Moyle and the Misty Isle [pre-war boats were painted, but the post-war ones were varnished]. And as a child, I used to go and sit in the fo’c’sles.

At the weekends, if there was a local football match, say in Glenelg, the men would take the boats down and we could all pile on the boats and go down there or over to Kyle at the weekend. And they would let us come on the boats. And it was just so magical.

And later on, if any of the men wanted to take a holiday or were off sick or anything, when I was a student on holiday, they would ask me to come and take their place. And I would work the cork rope and just generally get to know it.

And then for a while, I actually got a proper job there as the cook on the Misty Isle. By that time they were joined by another boat called the Fortitude and they were worked in conjunction with the Kyle boats, the Catherine and the Mary Anne. The whole community in Kyleakin, in the fifties and sixties revolved around the ring net boats.

There were some smaller boats that went for creels. But there were twelve men. Virtually all the families had a member of their family on the crew or relatives on the crew. The men came home at the weekend and I remember them playing the football. And a cruise liner called the Lady Killarney used to come in. And then the fishermen would play cricket on the green against the team from the Lady Killarney and then they would sing in the church choir and at the weekend they would mend their nets on The Corran, a green just outside the church. And they would take the young boys in and show them how to mend and how to bark. They would bark the nets on the on the Quayside as well. So I just grew up with it.

* * *

(pen and coloured ink, letraset, spray paint, watercolour on paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

The Ring Net is distinct from most of Will Maclean’s other work. Walking around Points of Departure, a retrospective at Edinburgh’s City Arts Centre that ran over the summer of 2022, one of the things that struck me was the feeling for language – in The Ring Net works, in the etched collaborations with poets, in the titles which often evoke narratives (memories, voyages and logs, catechisms and creeds, requiems).

At the same time, the matter-of-fact mysteries of the three dimensional works often seem to reach beyond the English language towards Gaelic culture. I asked him if that might have played a part in him doing something about fishermen in the West.

No, I don’t think it was consciously, because like so many young struggling artists, you take advantage of the opportunities that come your way. I have to say the driving force for the project was really getting myself out of teaching.

The project came about because I’d been teaching in a school, an art teacher, and I was complaining to Richard DeMarco, the gallery owner I used to show with, that I really needed a project to get my teeth into. At that time, he was chair of the Scottish International Education Trust, which was set up by Sean Connery and a number of other wealthy people of the time to fund projects that were related to Scottish culture and music and so forth. So I got funding from the Scottish International Education Trust to make a visual record of the ring netting, because that was what I knew about.

The education authority was great. They gave me a year out and gave me my job back at the end of it; they were amazing. It was ’73. I had no concept that ring netting was something that by the late seventies would have disappeared. I didn’t go into it thinking, Ah, I’ve got to do this before it changes or anything. It was just a continuation of the culture that I knew.

My mother said, There’s a man from Campbeltown: he knows about the fishing. That was Angus Martin who was working for the West Highland Free Press. For a while he was working on the Campbeltown ringers. So we met up and we teamed up. I said, Well, I’ll do the exhibition. And he said, Well, I’ll do the book.

It wasn’t casting around for something to do, but the natural thing for me to do was to make some kind of visual record. I was thinking about Joseph Banks and Captain Cook and the voyages where the artist was a recorder. I wanted to do something like that. I wanted to record things that people would not necessarily record unless they’d go into it at that depth.

When they went to toilet, what did they do? They had a drum, an oil drum with a tyre around the front of it, and they sat on that. How did they locate the herring in the early days? They used a piano wire with a weight on it and they unrolled it and they dragged it. And the old men knew by the strikes on the piano wire what fish were there and how many fish were there.

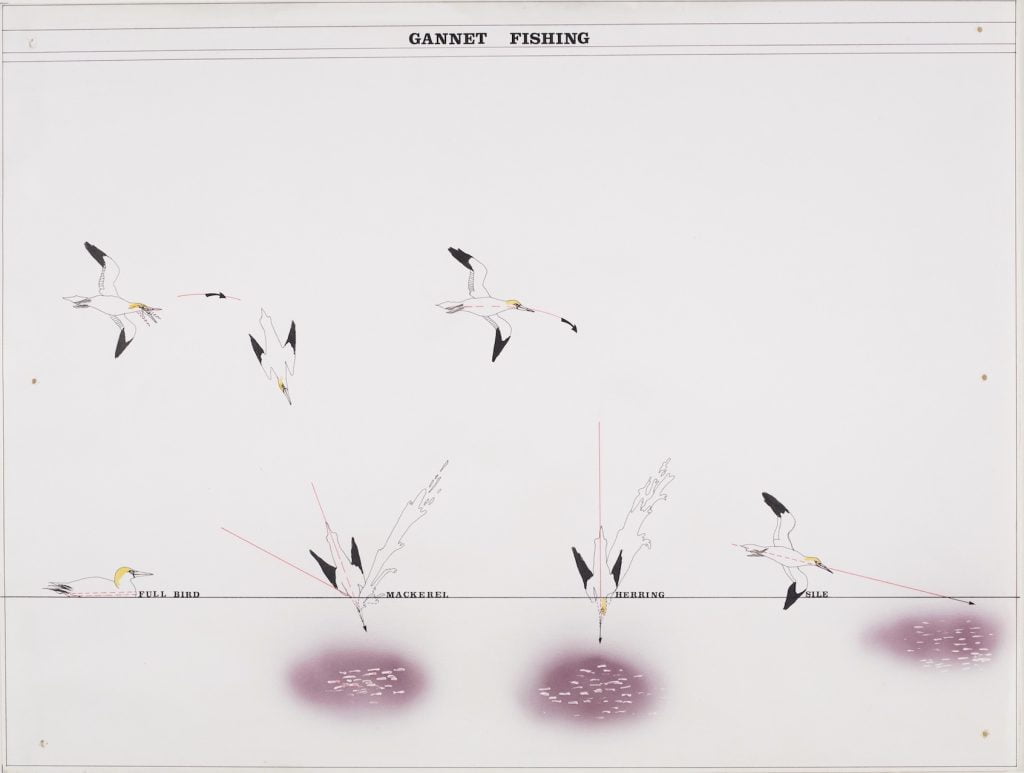

That level of detail was something that fascinated me. I wanted to record it. And Angus was the same. Angus had these amazing conversations with the men. And in terms of the recording, I soon discovered that you didn’t get much unless you could offer them part of the information. How many corks were on the leader? or how many this and that: then they would respond. If you sat down and said, Tell me about the fishing, they wouldn’t know what to say. But if you got into it and said, Why do you never turn against the sun? Why do you watch a gannet? Then the information would come out. And Angus was the same.

I mentioned Amber’s founder Murray Martin and his belief that people bring more to you when they recognise a commitment to their world. Amber had bought a caravan and horses when working with seacoalers on Lynemouth Beach in Northumberland; they’d bought a 36′ seine netter when working with fishermen in North Shields. Did Will’s and Angus Martin’s family connections and experience play a part in building the trust and respect out of which the material clearly flowed?

Absolutely. Angus had been a ring netter. His family were well known and respected. The old men talked to him endlessly. You’d be recording and halfway through the conversation, they would start to talk about other families and then they would say, Hope that thing’s not switched on… And really, that’s why with a lot of the tapes that I’ve got, I’ve never played to them to anybody, because I respected the fact that it was a conversation that we’d had in private. Of course, they’ve all gone to the Fiddlers’ Green now, anyway.

But that’s also why Angus treble referenced everything he did and everything he sent me. He said one of the big compliments that he had for his book was that none of the of the fishermen could find fault in it. And that was to him, the highest accolade he could possibly have. And the fisherman that did go to see the exhibition, they were puzzled initially that it should be important enough to be in an art gallery, but they were proud of it and proud of me for doing it.

I’m 81 now and I did that when I was a young man. So there are very few people left that could challenge anything because it’s part of history now. What I’m most proud of is that I managed to make some kind of record of stuff that otherwise would not have been recorded in that kind of detail.

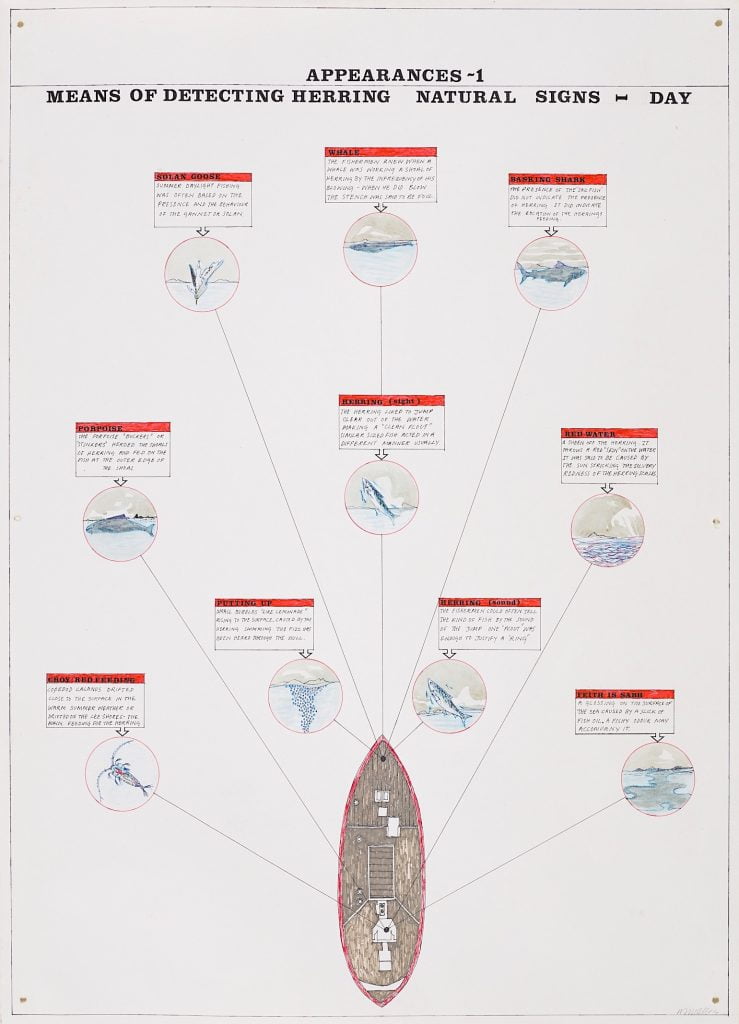

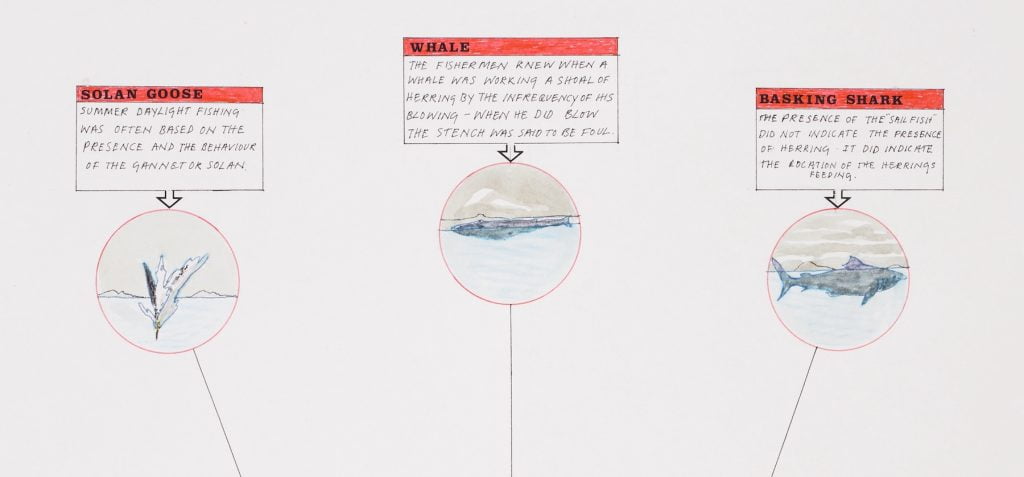

Particularly what fascinated me was this thing they referred to as Appearance, where prior to the advent of the echo sounder, which was quite crude really, they still relied on the old Appearance methods: banging the anchor to watch the herring, the reaction of the phosphorus.

I was amazed. I’d go out and stand with the old boys on the bow and they would chap the anchor and I would just see this flash like a light bulb under the water. And they’d say, Oh no, that’s mackerel, because the ball disappeared like a star. But when they saw something that was like a fat bulb going off in a flash gun, Boof! they’d shout back, They’re here!

It took me months and months, because you were looking at the surface of the water. You had to learn to look underneath the surface and when the sea was coming over, you were bouncing up and down and it was just an amazing thing to have the privilege to have been part of that experience, like watching the gannet going down or watching a whale breaching or watching for oil on the surface of the water: the signs, the Appearances as they call it.

But that went again with the development of echo sounding and radar and all the rest of it. The only non-appearance thing was the echo sounder. They would just come round and if the herring was on it, they used to call it a spot, spot mhor – it was more a black mark, really – and they’d say, That’s where they are! and they’d back round them and ring them.

(pen and coloured ink, letraset and watercolour on paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

* * *

As I’m changing the memory card in my recorder Will shows me another book, a tiny diary.

I’ve got a couple of diaries from a couple of the old men. Wonderful old diaries, you know, Nothing doing, and Half a gale blowing, nothing doing tonight. This is an extraordinary little book. It’s one of my most precious objects. The old boy, the man that gave me that, he had the Croix de Guerre. He was a man called Donald Reid. During the war they used to row the commandos in and out of France and because he was so skillful at rowing, because he could row so quietly, he would row them in. I remember taking him home one night from the pub and he opened a drawer and he said, See that thing there, boy? Do you want that? Take it away with you… So I had to give it back to his wife when I went out the door.

The story appears in Donald S Murray’s Herring Tales, in which Reid’s talent for listening to the herring is also noted. He was a Kyleakin fisherman and one of Will’s early sources. But there were limitations to Skye fishermen’s account of ring netting. One of the reasons the collaboration with Angus Martin became so important was because he tapped into the Loch Fyne tradition.

There’s this enormous depth of history in Campbeltown and Tarbert of ring netting that goes back right through the years. There wasn’t the depth of information in Kyleakin, because there wasn’t ring netting till after the war.

Ring netting had existed for a long, long time before, but right up until the seventies, there was huge resistance. There was resistance in Skye. One of my grandfather’s boats, the Star of the Sea, had a ring net and they hid it in the bows. When they would go fishing, they would shot the ring net, then they would hide the ring net and the buyers would say, Why are these fish so clean? Why are they not hung? [With drift nets the herrings are caught by the gills and have to be shaken out.]

The Sea League [an organisation set up by Compton Mackenzie and John Campbell in 1933 to protect traditional drift netting in The Minches] was based in Harris, or really Scalpay. It was a hot bed of resistance. Although, ironically, the last of the ringers fished out of Scalpay. So it took a long hundred years before the ring net was accepted and established, particularly in Skye, in my area. By the time it was established, it was quite a brief period, relative to the history of ring netting, before it all came to an end.

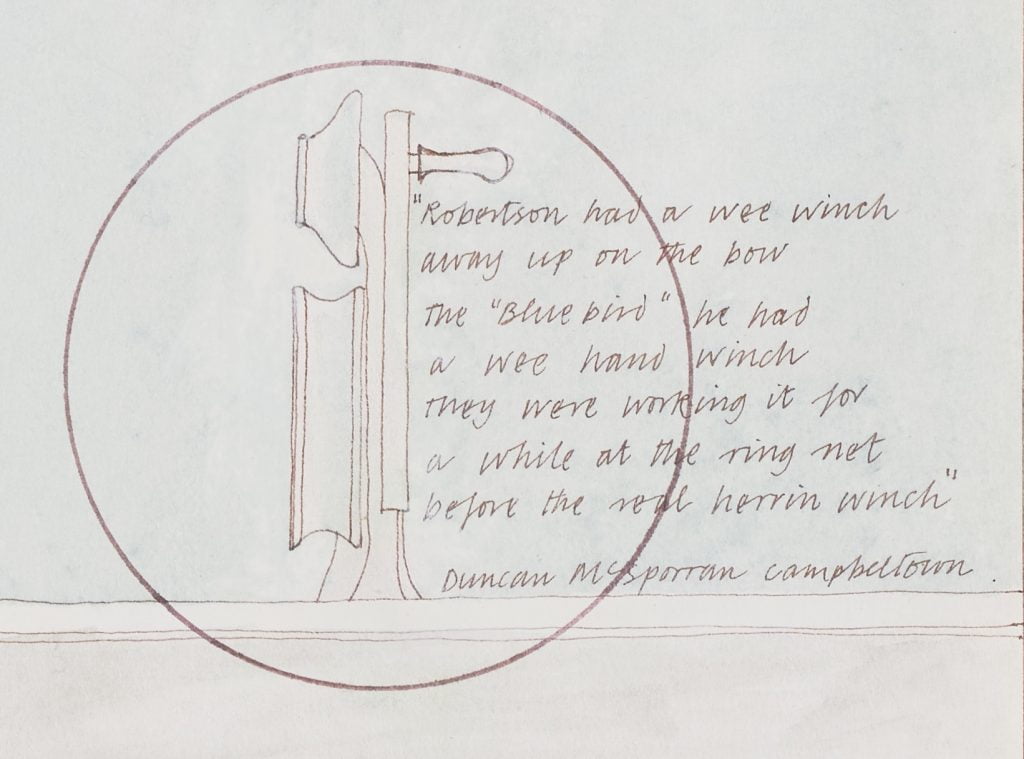

It was three or four years Angus and I worked together, back and forth. He collected a phenomenal amount of information, checked and double checked: every reference completely sound. And then he would send me rough drawings of whatever I was interested in. I was back to school teaching by then and I used to get the kids busy, then I’d go and draw a tractor.

(pen and ink and watercolour on paper).

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

He pulls another volume from the shelves, a thick file of carbon copies.

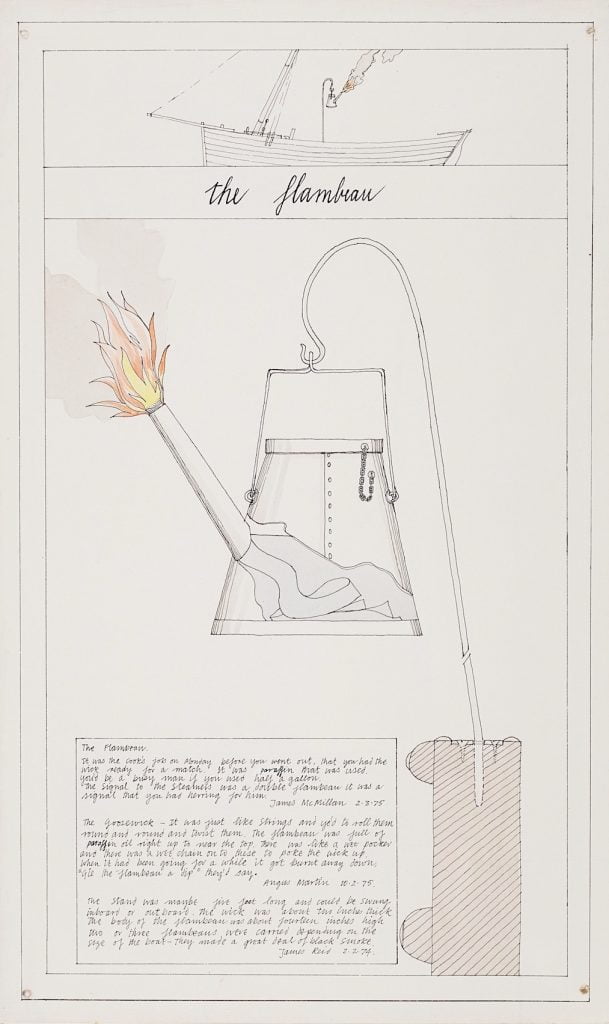

These are all the letters that Angus wrote, back and forth. I made this book up so that I could refer to different things, Dalintober, Driftnet, Dogfish… So that when I came to make the drawings, I could refer to the text. But also Angus actually drew the lamps and how they hung and where they hung paraffin lamps, so I could do a section on paraffin lamps.

I would write to Angus and say, How did they make the buoys in the old days? And he would write back and say, Well, there were certain farms that bred dogs for their bladders. And these farms would sell the bladders to the fishermen and then it went on to canvas and then it went on to plastic. That’s the kind of thing that interested me.

He’d spend hours talking to the old boys and he would ask them about this and that and then, if I said to him, Do you have any information on flambeau? (the lights they held up at night) he would go through his archives or he would maybe go and speak to them again and say, How did the flambeaus work? And some of them would talk about all the tricks they would have.

In the early days, once the Loch Fyne skiffs hit the herring, they would light the flambeaus to tell the other fishermen where they were, but sometimes, when there was no herring, they would just light the flambeaus to attract the other boats and then they would go away. They’d light the flambeaus and go off, because they wanted to get them away from where they knew the herring were. There was all kinds of stuff going on…

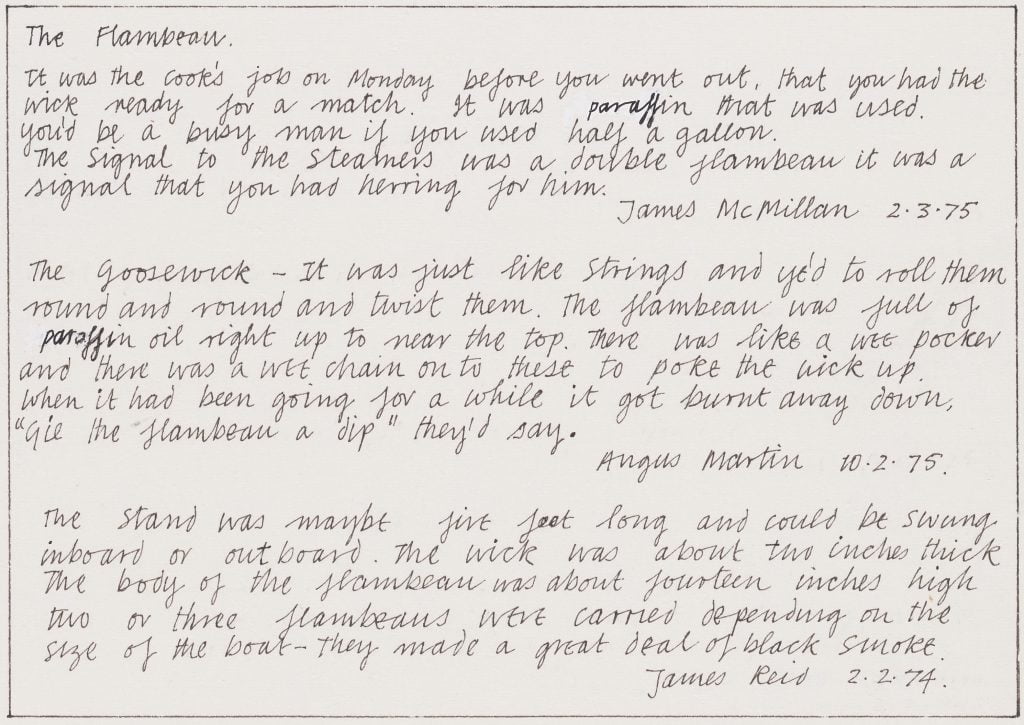

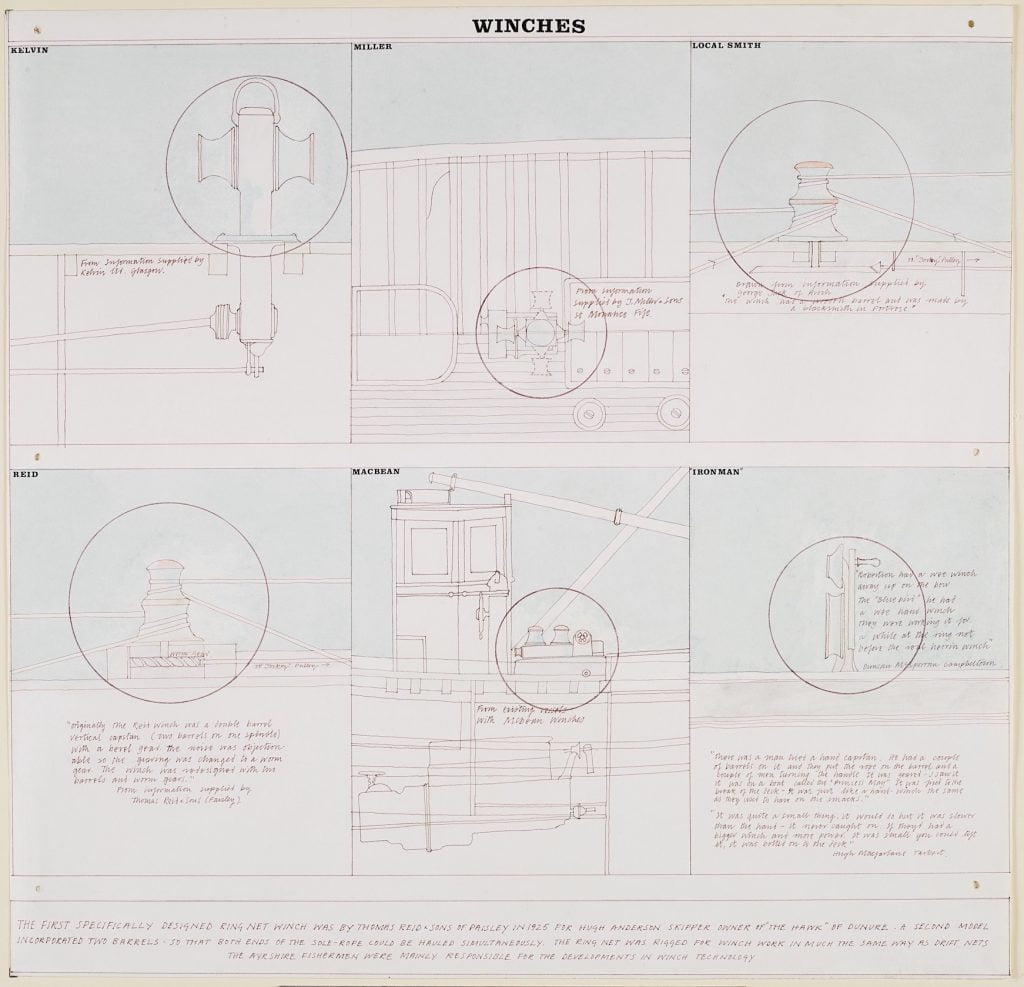

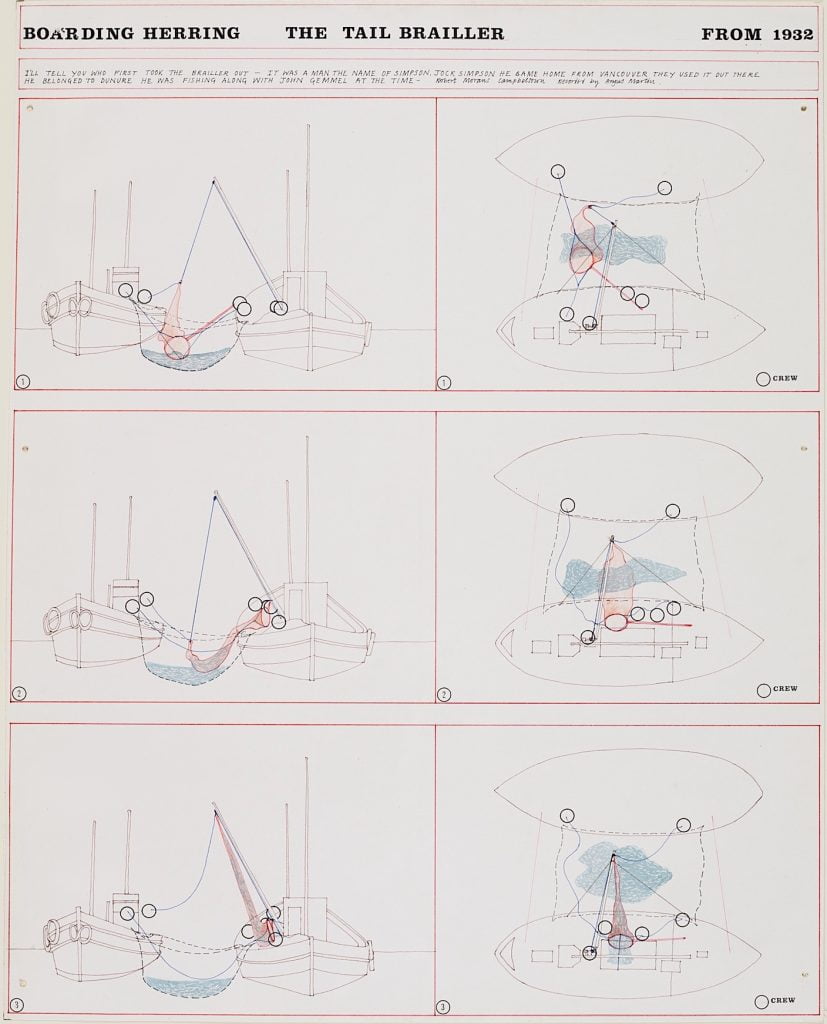

If I did a set of drawings of winches, I would start with a McBain winch. And then Angus would send me a photograph of an earlier winch and I’d write to the manufacturers and they’d send me drawings of winches. So I could build a sheet up: this was the development of the ring net winch. And it was the same with the brailing – for lifting the herring.

I wanted to have a notion of a progression really: the technical development. I didn’t think I was doing a documentary because I didn’t know about documentaries and I didn’t feel that I had any kind of knowledge or skill in that direction, which is interesting. I just wanted to make the art side of it. Whereas Angus Martin, coming out of a different culture, he was much more aware of the history and the relationships with the families.

(pen and sepia ink, Letraset and watercolour on paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

In much of the best documentary photography, there’s a spontaneity that derives from what Cartier-Bresson called the decisive moment – no matter how much it is later considered and curated, it gives an energy and ambiguity to the image that, in any great photograph, is usually beyond a photographer’s capacity for conscious intent. One of Will Maclean’s favourite artists is Joseph Cornell. One of the things I like about his work is that when you look at the way he’s put his frame around it, he’s used a screw with a dome head on that side and a flat screw on that side. I really love that kind of ‘I’ve got to screw it up…’ and ‘Oh, there’s a screw!’

There’s a spontaneity in The Ring Net that lies in the construction of the drawings – and overwhelmingly in the combination of image and text.

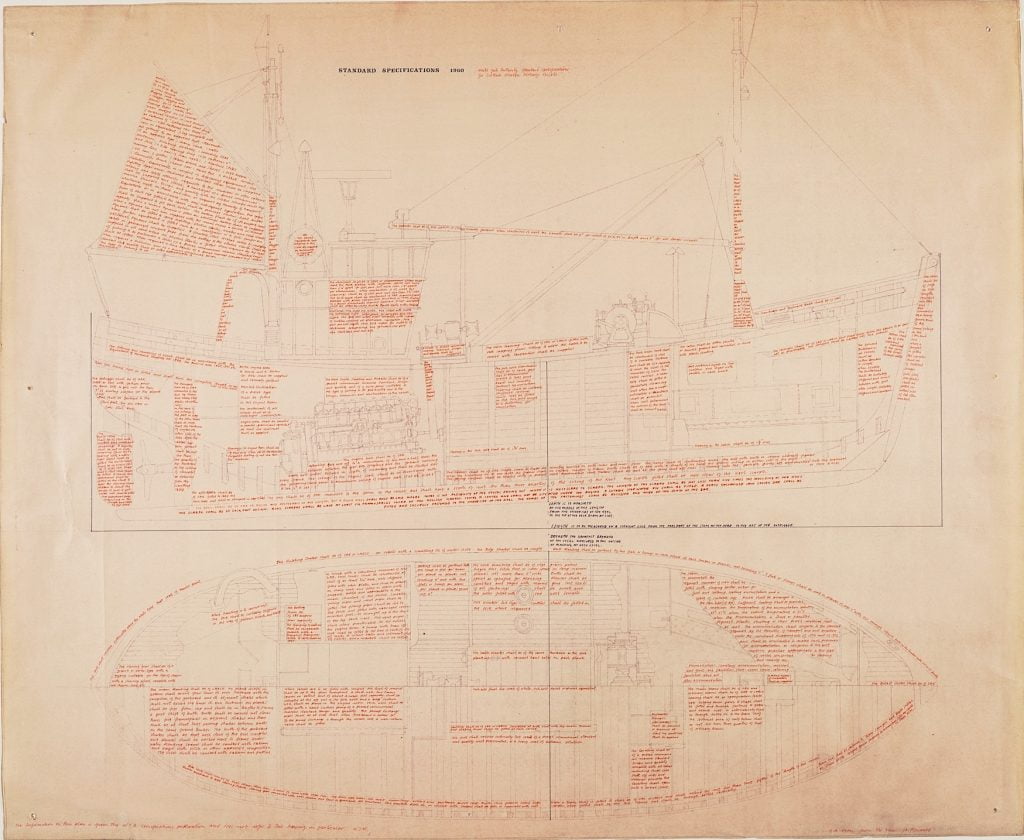

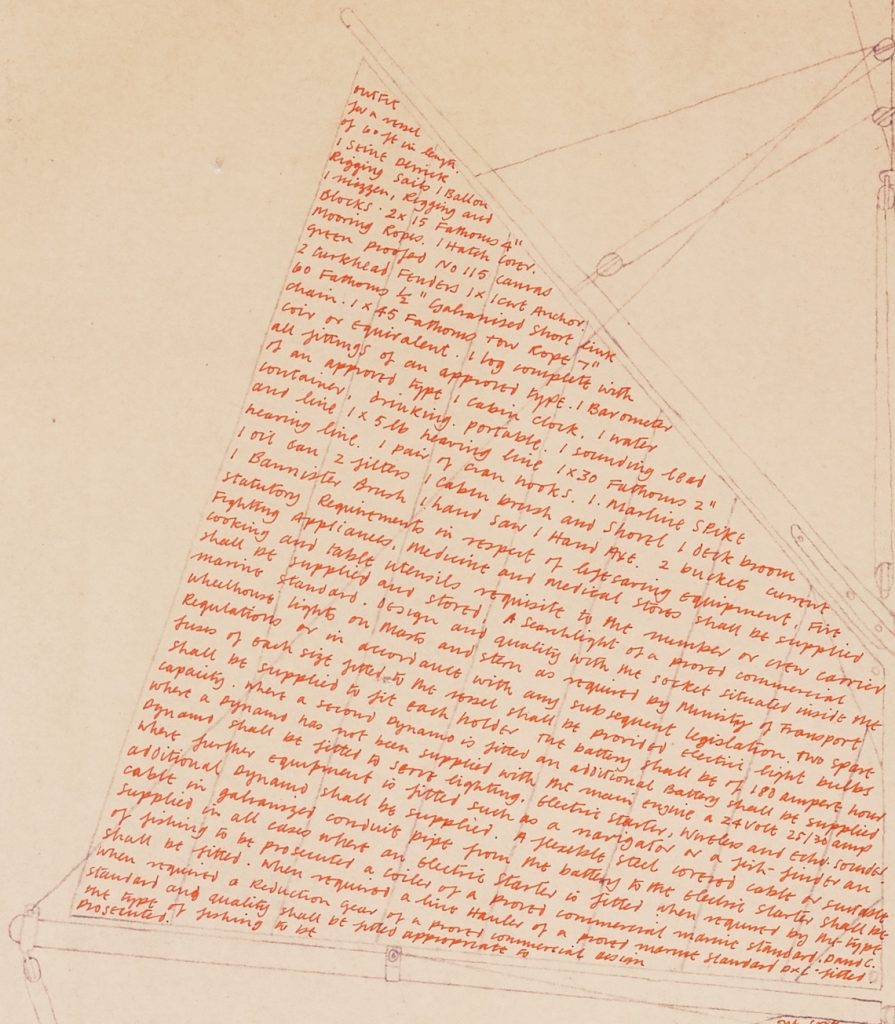

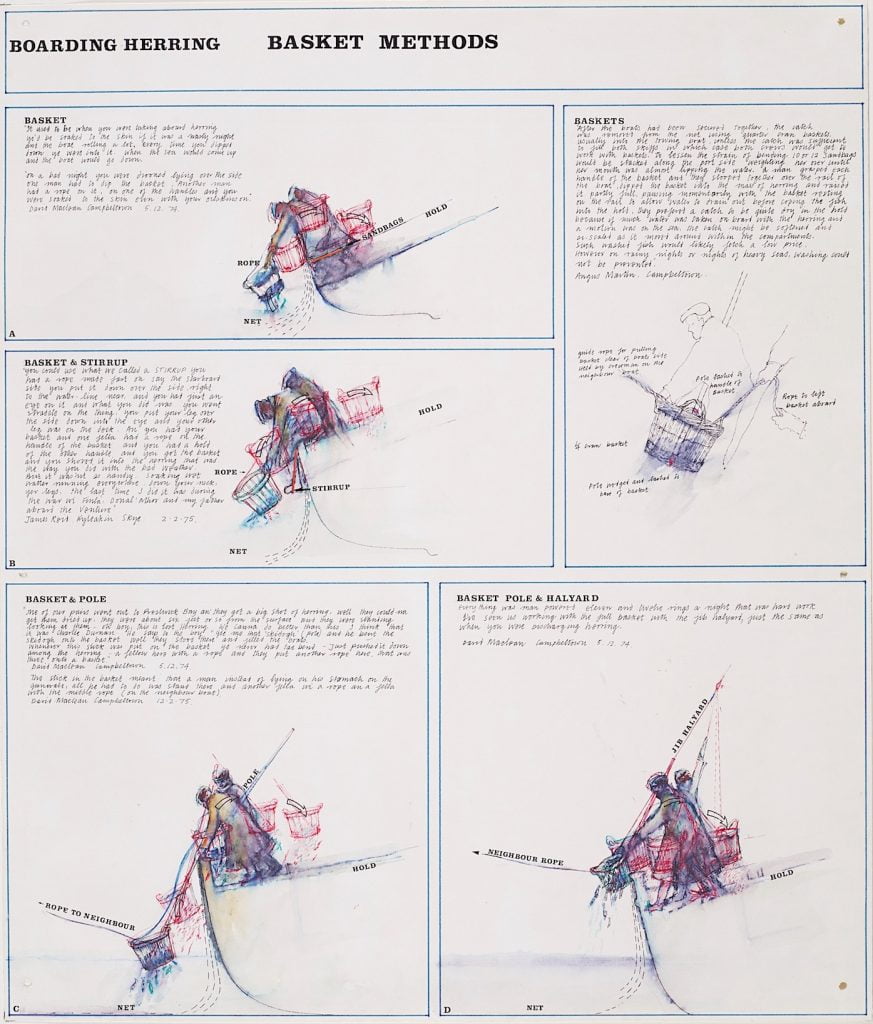

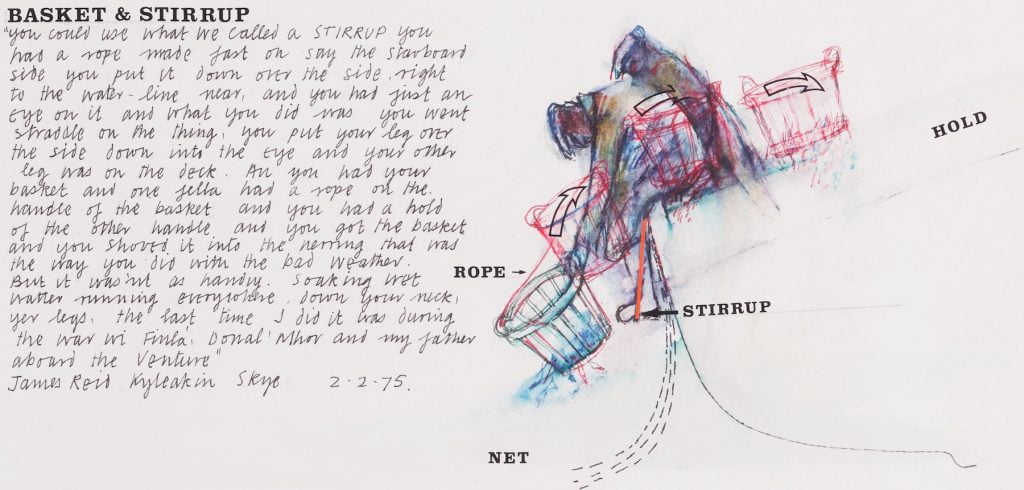

If it was a thing like a sail – the little mizzen sail that they put up to keep the head to the wind – I could draw a sail, but then if I wanted to add to it by saying when the sail was hoisted and what the sail was made of and when it was used, it was something I did – just to inform the drawing, really. The text never came first. The drawing always came first and the text was something added in to inform it. I must say I wasn’t in any way precious about it. It was just something that I did at the time. I just wanted to have a thing that had as much information about it as I could put into it.

In its focus on the mechanical details, The Ring Net is unlike most work in the documentary tradition, but that’s part of its narrative freshness. The small texts can fill a mizzen sail or a rudder or a net attached to the boat’s side. They can sit in a discreet box at the top or bottom of the image. They might just be jotted notes beside the drawn details they describes. They can be Will’s own notes or Angus Martin’s. Or they can be something transcribed from a tape recording of a conversation with a fisherman. The recording might have been made by Will, although most were made by Martin.

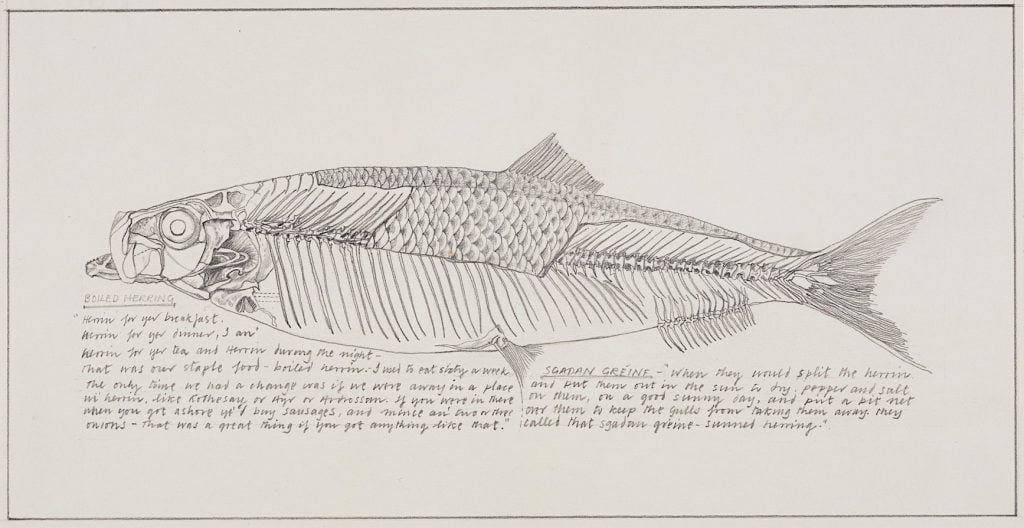

For me, the drawing that most conjures up an artist’s notebook on an imagined voyage of discovery is of a herring, almost half-filleted to reveal the detail of the skeleton. Two handwritten fisherman quotes square off the image, separated by the pelvic fin.

BOILED HERRING

“Herrin’ for yer breakfast, herrin’ for yer dinner, I an’ herrin’ for yer tea and herrin’ during the night – that was our staple food – boiled herrin’. I used to eat sixty a week. The only time we had a change was if we were away in a place wi’ herrin’, like Rothesay or Ayr or Ardrossan. If you were in there, when you got ashore ye’d buy sausages and mince and two or three onions – that was a great thing if you got anything like that.”

SGADAN GRÉINE

“When they would split the herrin’ and put them out in the sun to dry, pepper and salt on them on a good sunny day and put a bit net over them to keep the Gulls from taking them away, they called that sgadan gréine – sunned herring.”

As with all the drawings incorporating these texts, the close juxtaposition, tying the words to specific details, opens a world beyond captured objects. The mechanics suddenly open up on the lives, the histories, the culture and practices vested in them. Quite literally, the objects speak.

(pencil on paper).

Courtesy of National Gallery of Contemporary Art, Edinburgh.

* * *

The texts can be in narrow line caps or thicker line handwriting. The logic seems only to be in the spontaneity of the drawing’s creation. Letraset titles evoke the 1970s more than most of the graphic elements, but there’s a similar inconsistency its use. It isn’t there on every sheet. What matters is the record.

Two things intrigued me at the time. One was Letraset, because it was amazing that you could use Letraset – you got proper letters! And the other thing is I had an airbrush which, again, quite fascinated me and I used wax resists and that whole thing…

We did four years in art school: two of them were the general course, two of them were graphic design. So I wasn’t entirely naive about the kind of notions and structures of graphic design. The guy that taught me graphic design, Fred Stiven, was a really interesting artist as well. I just loved the whole notion of graphic design. Artists like Eric Ravilious and Bawden, I just love them. I never tire of Ravilious – Sickbay in Dundee with the aircraft outside the window, it’s amazing! I’ve got several books on Ravilious…

The Rotring was another thing: the Rotring pens. But I gave up on Rotring because it was so fiddly in there. I went back to mapping pens. I still use a mapping pen, the old nib. The Rotring is very mechanical. It just gives you one line, but a mapping pen gives you different fat lines and thin lines. You get different qualities: such a simple tool and it’s just so magical to use.

I’d just write to the space I’d created. It’s all drawing after all. Text is just a different kind of mark-making. It’s got another side to it.: you can read it. But in terms of making it, it was a series of marks in my mind. It was a series of marks that enhanced the composition of the work.

Behind the drawings, there are the cassette tape interviews, Angus Martin’s drawings, Will’s own photographs, plans of boats carefully traced from originals lent him by different yards. Some were included in the exhibition as primary source material along with copies of documents. Angus Martin’s interviews were given to the School of Scottish Studies, but a sense of the full scale of it still fills boxes, box files and folders on Will’s shelves.

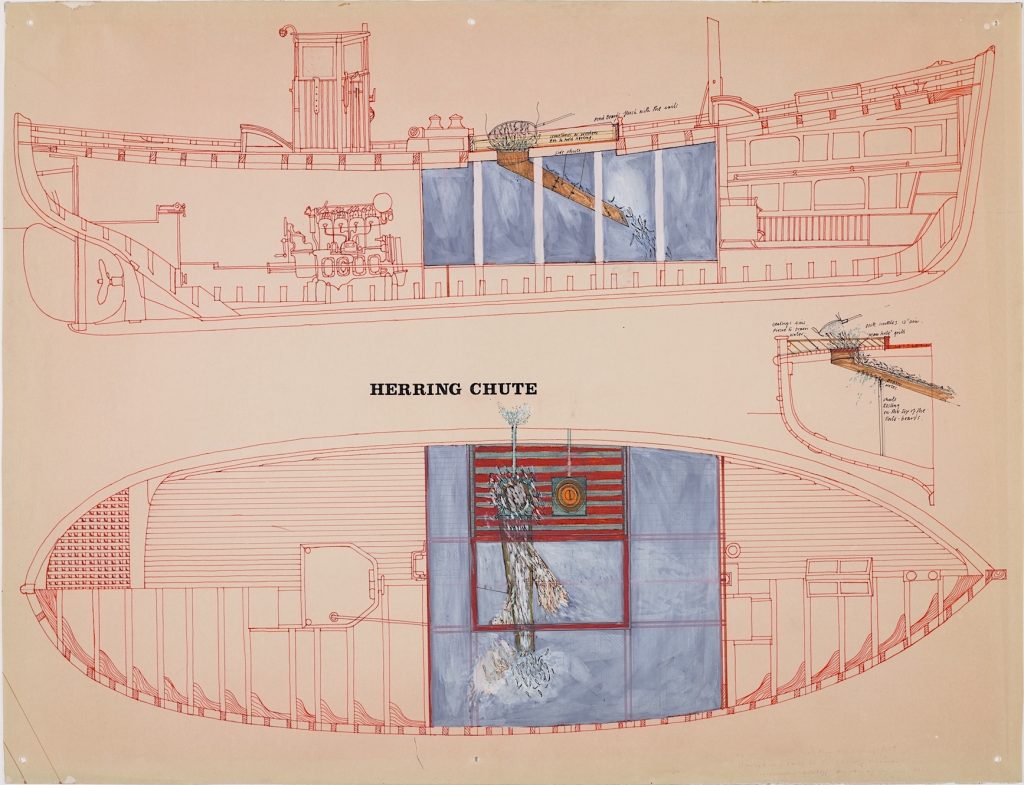

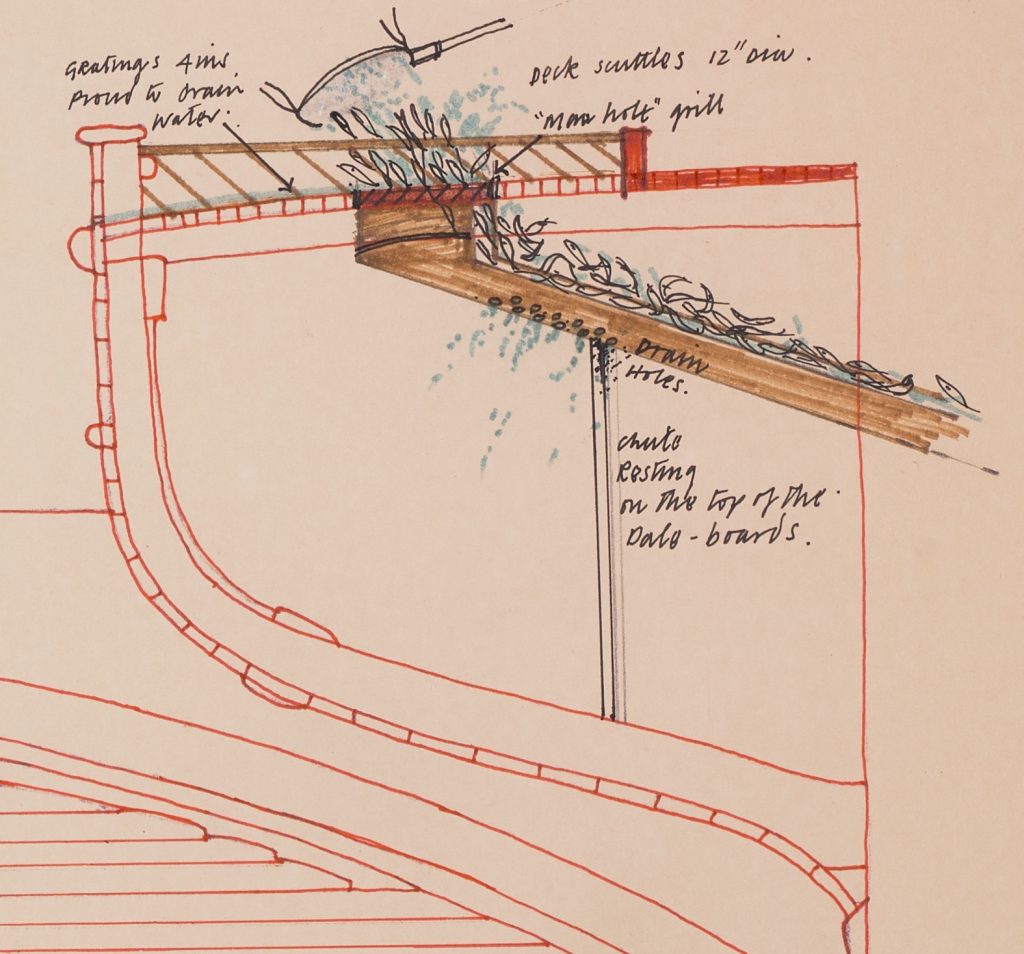

There’s a boat plan in the archived exhibition, Standard Specifications 1960, which is not a million miles away from William Hodges’ Draught Plan and Section of the Britannia Otehite War Canoe, the original of which was drawn while Hodges was the official artist on Cook’s second voyage. Except for the level of information, perhaps. In Hodges’ plan each note on construction has a letter corresponding to one neatly placed on the war canoe plan. In Will’s ring net version, the whole image is covered in red ink notes – on mizzen sail, rudder, stern, keel, stem, masts, spars and more, a cramming of information in what seems like all you’d need to recreate and work a ring netter.

(photo print, pen and red ink, letraset on paper)

Courtesy of National Gallery of Contemporary Art, Edinburgh.

I would photograph things for a record. There are some I took of fishing at night, that were interesting as photographs, more art photographs than carriers of information, but [pointing at a box file] there are thousands of my photographs in that. I could only afford to print some of them. And then there are the ones I copied… I would go down and stay with Angus… One guy lifted the corner of a carpet and he had all these old black and white photos under the carpet and he’d say, Oh, that was the wee Toon Flyer. Aye, that was… and I used to just snap them when I could.

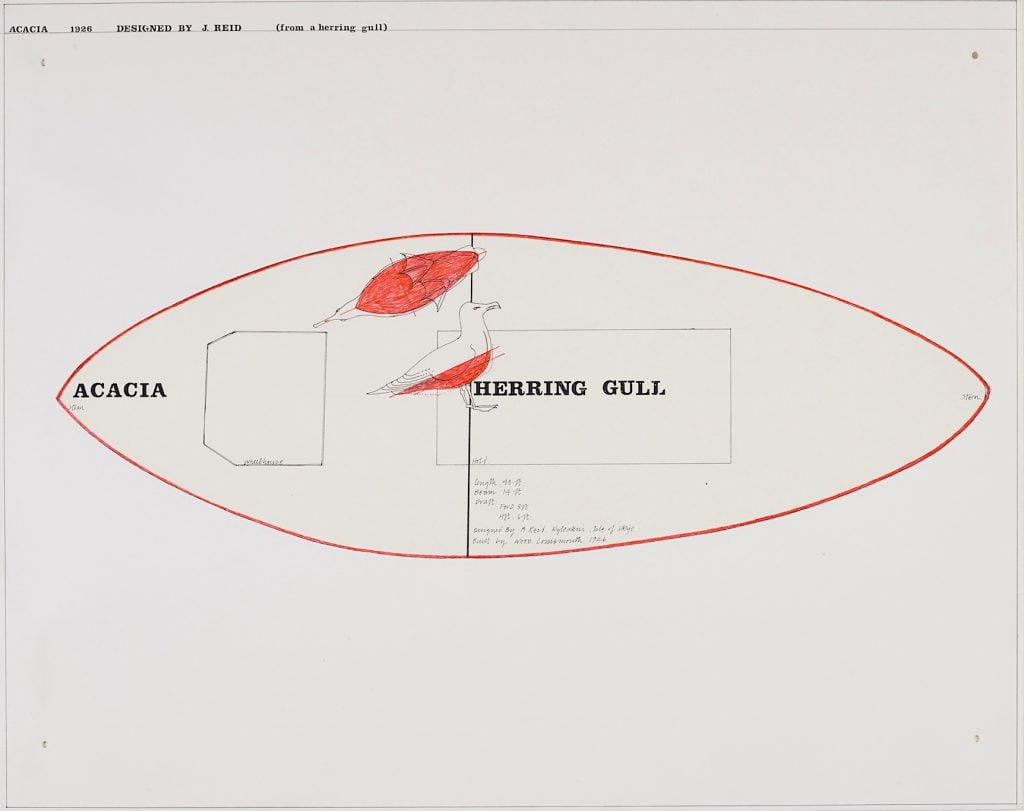

Sometimes I would sit down with the Kyleakin men. There’s an interesting boat called the Acacia. It was designed on the body plane of a herring gull. I sat the old fellers down and I’d say, With the fo’c’sle, what was the layout there? And Where did the winch belt go through? And where was the Jack Tar stove? I used the photographs. I didn’t think of them as art or anything. And when it came to the exhibition, I tended not to use the photographs creatively. I just bunged them all together. Because I didn’t have much money, I just got big boards. There were boards of photographs and then boards of ship developments. It was a very basic presentation.

Among the Ring Net works, almost the polar opposite to Standard Specifications 1960, there’s a simple drawing of the Acacia seen from above. It was designed by a fisherman based on his study of herring gulls. Below the gulls, the boat’s length, beam and draft measurements are given and, still within the lines of the boat it says, Designed by A Reid, Kyleakin, Isle of Skye and Built by Wood, Lossiemouth 1926.

(collage, letraset, pen and red and black ink on cartridge paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scxotland.

There’s humour in the THIS – THIS simplicity of the titling and in the blood red gull slices describing the part taken into the boat’s design. Behind that, though, there is a rich evocation of a life: a fisherman who thinks about fishing, who worked boats and thinks about boats, who looks at seabirds on the water and takes delight in the practical beauty of natural forms, who has the independence of thought to experiment. With remarkable economy it makes the values of a community and culture concrete. It’s a joy.

(pen and coloured inks, Letraset, red pencil and watercolour on paper).

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

* * *

I found the list of exhibition works in The Ring Net: Ring Net Herring Fishing on the West Coast of Scotland; a Documentary Exhibition by Will Maclean, an MLitt thesis by Patricia Allerston from 1991. It’s invaluable when you’re trying to get your head round it all – especially when you’re looking at pictures as they come out of the archive or as they have been selected for the representation in the City Art Gallery retrospective. But it can be misleading, particularly if you’ve spent twenty years trying to construct documentary narratives.

The exhibition wasn’t done in any order. It was done through this old file, really [holding up the filed exchange of letters with Angus Martin]. There was a section on Appearances, there was a section on Developments of Boat Hulls and so on. The sequences were all just within the subject. For example, the Development of the Decks over that period of time – the Loch Fyne skiffs were open, then they became part-decked and then they became fully- decked… And now I’ll talk about the Development of the Net: how did it develop over different stages? I just hopped from one thing to another.

As to the order of the sequences, the exhibition toured around and it depended on the curatorial responsibility at the time. The DeMarco gallery had it and he just hung it the way he wanted to hang it within the gallery space. He treated it in the ordinary way he would treat art objects.

When the tour was all finished, I offered it free to the Scottish Fisheries Museum and the director of the time, I went down to see him and he said to me, Oh, just leave it. We’ll think about it. Just leave it there… I thought, No… No… It’s a kind of anomaly that it’s where it is, but I got the offer from the National Gallery of Modern Art and I’m delighted that it’s where it is. It couldn’t be in a better place. And it’s wonderfully looked after. It’s treated like you would treat any other work of art. It’s fantastic to have it there, but I couldn’t believe that the Fisheries Museum didn’t seem to be too interested in it. It was just the director at the time. Maybe it was a bad day for him or something. He didn’t really focus on it. I don’t know. But anyway, there we are. I love the museum.

(pen and red and black ink, gouache, letraset, acrylic pen over photo plan print, on photo plan print paper)

Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

In work written about The Ring Net, there’s a recognition of its importance, but it’s hard to avoid a sense of uncertainty as to exactly where it sits in the scheme of things. I talked to Will about the experience of documentary photography in England, where, particularly in the 80s, 90s and 2000s, the contemporary visual arts pretty much dismissed it. Prevailing post-modern orthodoxies, a desire to see clear demarcation between art and social history or journalism, being too closely associated with the losing side in the Miners’ Strike of ’84: you could take your pick of logics, but there was no denying the withdrawals of funding. Had Scotland’s experience been different? Had any of this played into the way The Ring Net was looked at. He recognised the uncertainties, but suggested another narrative.

When I was doing The Ring Net, in Scotland, Glen Onwin was the only other visual artist working what could be called a documentary project: he did an exhibition on dissolved substances. In terms of education, it wasn’t until the art schools joined with the university and the whole notion of research became established that they recognised The Ring Net as a research project. It fitted into the notion of a visual PhD or something that had academic credibility, because it could be overprinted with the traditional academic notion of what research was about.

When I did it, I didn’t know anything about research and in terms of an art project, you’re right, it was something that was, at that time, completely different. I went to art school and for four years I studied painting and there was no notion, going through an art school in the sixties, that something like The Ring Net could have been considered as part of the visual arts.

But, as I said earlier, I didn’t think I was doing documentary either. The only thing was this loose notion of Banks and Cook and the early drawings that came back of strange fish and plants and things like that – extraordinary, wonderful stuff. That was the only kind of role model that I had in mind, really.

I think the thing to remember is that I had no notion that ring netting was anything but an ongoing tradition I was dipping into. I was focusing on something that had always been there through my life, through my childhood.

I didn’t have any clue that, within 10 years or so, the pursers [the purse seine net fishermen] would have put paid to ring netting… and that the whole extraordinary community, that revolved around Mallaig and Kyleakin and Applecross and Kyle and Campbeltown and Tarbert, would just disappear.

It wasn’t overnight, but it wasn’t far off it. I think Angus probably realised that earlier than I did.

I thought of the work as a kind of rehearsal. I can draw a ring net boat with my eyes closed, because for years I traced plans and I studied it. When I look at William McTaggart – a boat that William McTaggart draws – I know that McTaggart knew about these boats. You could go to sea in a McTaggart boat.

The whole process of The Ring Net informed the rest of my work. If I sit down with the sketchbook, I have this kind of reservoir of information that was garnered from the research. It’s that rather than the work being either something separate or something that sits together with the rest. The paintings that I did at the time of ring net boats were terrible and I’ve fortunately destroyed most of them. It was a bit like learning how to life draw.

In terms of how it fitted into my life as an artist, it was an event. And then it was finished and I went back to making box constructions and stuff. It fed off that information, but it had nothing to do with anything documentary.

If I’m stuck for an idea when I’m working in the studio, if I’ve an exhibition coming up or somebody wants something for an auction, I’ll sit down and I’ll draw a landscape and I’ll put a ringer into it and it’s just always there in the back of my mind.

There’s a big piece that I did, Skye Fishermen in Memoriam – it’s in the Points of Departure exhibition – it was a piece about my uncle and the ringer. But strangely enough, I used a bit of a box from a boat called the Antares and that was the boat that was dragged down by the submarine and the men were lost. I did that before the boat was lost, but it became, in my mind, a painting, not Skye Fishermen in Memoriam, but Fishermen in Memoriam because it has that context of that Antares box in it. It is just complete chance, but it has a very sad connotation. Like most artists, I don’t know where my work’s going to take me next, but certainly I have this reservoir of this information and of reference that I can pull out, all because of the ring net project.

Maybe it’s too parochial or too referential, but it’s all I can do. That’s what I know and that’s what I can do and that’s what I have been doing for 50 years. People get it or they don’t.

For me, obviously, Points of Departure could have shown even more of The Ring Net, although not at the expense of any of the other herring works – actually, not at the expense of any of the other works. There was an extraordinary richness of vision across the retrospective. The works seem to start in an understanding of just how much there is to know.

I felt quite strange walking into a major gallery and seeing these works I did 40, 50 years ago up on the wall. My first reaction was being glad that they haven’t fallen apart and probably the second reaction was that, with the ones that aren’t painted, anyway, age has given them a patina that I really like. They’ve been hanging in people’s houses when the sun’s been on them, so they’re bleached. And I like that. I like that kind of aging – something that I wouldn’t even have been able to do. I wouldn’t have been able to fake it.

I’d dearly love, at sometime in the future, to see a publication of the ring net drawings and work, but I doubt if that’ll ever happen.

It should. Hill & Adamson’s The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth was the first documentary photography narrative (long before the term became current); Grierson’s Drifters was the first documentary film; the innovation that was Charles Parker, Ewan McColl & Peggy Seeger’s series of Radio Ballads only really found its feet with the second broadcast, Singing the Fishing. Whether intentional documentary or not, Will Maclean’s The Ring Net is a work of documentary art of this order, significance and beauty.

Acknowledgements

I first heard of Will Maclean’s The Ring Net from Ann Macleod. Her husband, Ali ‘Beag’ Macleod, who had recently died, was a cousin of Will’s. My good friend, the artist Keith McIntyre put me in touch with Will, enabling the interview. I am indebted to Kerry Watson who showed me the exhibition in the archive at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh and who helped with information and facilitating the supply of the images illustrating this entry. I’m very grateful to National Galleries of Scotland for permitting the use of them. Most of all, I’d like to thank Will Maclean for the interview and both he and Marian Leven for the generous welcome they gave my wife and I at their home in Tayport.

External Links

See also

- BRITISH FISHERY

- BRITTEN

- BUSS

- CALLER HERRIN’ (FILM)

- CALLER HERRIN’ (SONG)

- DRIED HERRING

- DRIFT OR GILL NETTING

- DRIFTERS (DOCUMENTARY FILM)

- FIFIE

- HARENG SAUR

- HARENG SAUR MONOLOGUES

- HERRING BUSS (TUNE)

- HERRING’S HEAD

- KIPPER

- LOCKMAN, JOHN

- LUGGER

- MUIR, JIM (HERRING INTERVIEW, ACHILTIBUIE)

- NASHES LENTEN STUFFE

- NEUCRANTZ: ON HERRING (1654)

- OATMEAL

- PARA HANDY

- PURSE SEINING

- RED HERRING

- RED HERRING JOKE, THE

- RING NETTING

- ROLLMOPS & BISMARCKS

- SHOALS OF HERRING, THE

- SINGING THE FISHING

- SMITH, ADAM: WEALTH OF NATIONS

- TRAWLING

- ULLAPOOL

- WHEN HERRINGS LIVED ON DRY LAND

- WILLIAMS, WILLIAM CARLOS: FISH

- YAWL

- ZULU